Opera Album Review: A Stirring “Samson,” Written a Decade Before Saint-Saëns’s, Receives Its Premiere Recording

By Ralph P. Locke

Joachim Raff, widely hailed for his instrumental works, is finally being recognized as a significant opera composer as well.

Joachim Raff: Samson (grand opera in five acts)

Oleh Tokar (Delilah), Magnus Vigilius (Samson), Robin Adams (Abimelech), Christian Immler (High Priest), Michael Weinius (Micha), and other soloists.

Chor der Bühnen Bern, Bern Symphony Orchestra, cond. Philippe Bach.

Schweizer Fonogramm Suisa 91357 [3 CDs] 184 minutes.

To purchase or try a track, click here or here.

Recently, I raved about a comic opera from the early 1880s by Joachim Raff (1822-1882), Die Eifersüchtigen, that has recently been performed for the first time ever and then released in an excellent recording. I am pleased to report that Raff’s five-act grand opera Samson is now also available in a recording. This release shows with equal clarity what European culture missed when, for complex reasons, Raff — despite great success as a composer of piano pieces, songs, chamber music, and symphonic works — was not embraced as an opera composer.

Recently, I raved about a comic opera from the early 1880s by Joachim Raff (1822-1882), Die Eifersüchtigen, that has recently been performed for the first time ever and then released in an excellent recording. I am pleased to report that Raff’s five-act grand opera Samson is now also available in a recording. This release shows with equal clarity what European culture missed when, for complex reasons, Raff — despite great success as a composer of piano pieces, songs, chamber music, and symphonic works — was not embraced as an opera composer.

The immensely talented, Swiss-born Raff was partly self-taught (a bit like Berlioz). He caught the attention of Mendelssohn early on and became a musical assistant to Liszt (possibly helping orchestrate some of Liszt’s symphonic poems). Later, Raff became disenchanted with Liszt and moved to Wiesbaden. There, he established a freelance career for himself as a piano teacher and much-published composer. This was back in the days when one could make a living (as Brahms, among others, did) by publishing musical works intended for the concert hall and for amateur musicians. Unfortunately, only two of his operas managed to get performed — receiving little acclaim — while the remaining four did not reach the stage during his lifetime.

As a result, today we sometimes witness the unusual situation of world premieres for Raff operas composed more than a century and a half ago!

A few years ago, I hailed his gentle and touching comic opera Benedetto Marcello and, as I said, I let you, my devoted Arts Fuse readers, know about his fizzy, almost daffy final opera Die Eifersüchtigen. Now we have the world-premiere recordings of his five-act biblical opera Samson, composed in the years 1851-57, with a libretto by the composer (another feature that Raff shares with Berlioz and, of course, with Wagner). The recording was made possible thanks to the heroic efforts (as both editor and organizer) of the music scholar Volker Tosta, his publishing firm Edition Nordstern, and some crowdfunding. An eight-minute trailer includes recorded snippets from the recording, as well as on-camera interview with the performers:

Samson, though in German, is otherwise a typical example of a French Grand Opera. (Opera historians capitalize the genre to distinguish it from, say, all grand operas performed in French-speaking lands, a potential confusion because even the ones by Verdi or Wagner, were, until recent decades, generally performed in French translation.) Auber and Rossini had more or less created French Grand Opera, in, respectively, La muette de Portici and Guillaume Tell; and the genre achieved full expression in several works each by Meyerbeer and Halévy, and also in such diverse works as Félicien David’s richly tuneful 1857 Herculanum, Verdi’s magnificent and disturbing 1862 Don Carlos, Berlioz’s alternatingly majestic and intimate Les Troyens (completed in 1858 but, during the composer’s lifetime, performed without its first two acts), and Saint-Saëns’s stirring and psychologically insightful 1883 Henry VIII (recently recorded by Boston-area-based Odyssey Opera. Wagner’s Rienzi, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin have long been recognized as deeply indebted to French Grand Opera (and the latter two were among the works that, as I mentioned above, were, until the mid-20th century, performed in French in French-speaking lands).

Raff’s Samson was finished around the time that Saint-Saens was just starting his own setting of the biblical story, entitled Samson et Dalila. Ironically, Saint-Saëns’s opera premiered under Liszt’s auspices in Weimar in 1877 and eventually became a repertoire staple, whereas Raff, who had broken with Liszt in around 1856, never got his version performed there or anywhere else, thus leaving the challenge and opportunity to scholars and performers in the distant future.

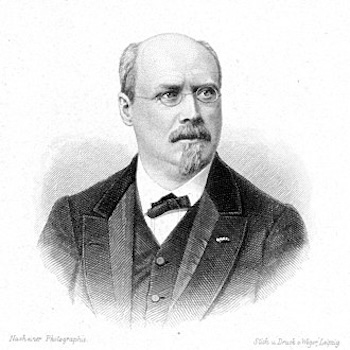

Composer Joachim Raff. Photo: Wikimedia

The plot will be somewhat familiar, because, like that of Saint-Saëns’s renowned opera, it is based ultimately on the story in the biblical Book of Judges. The recording comes with two lavish booklets. The first contains highly informative essays, including one by the Raff expert Volker Tosta. The second offers the libretto in German, plus excellent French and English renderings in separate sections — not, alas, in parallel columns. (The English version was prepared by my longtime Eastman School colleague Jürgen Thym, renowned for his scholarly work on the relationship between music and text in German art songs.)

Raff consulted scholarly writings when preparing the libretto, one result of which is that certain names are closer to the Hebrew or other ancient terms than to their usual German or English equivalents. (On the title page of the manuscript, Raff carefully wrote the title in Hebrew letters, above the normal spelling.) Most crucially, the Philistines here are referred to as the Pelistim, a biblical term for the people. At one point, Delilah prays to the goddess Baaltis.

In this opera, Delilah is in love with Samson, not at all feigning her feelings. In the Saint-Saëns, by contrast, she claims — to the High Priest — that she hates the Israelite warrior. But, as I have argued in my book Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and, in more detail, in an article in Cambridge Opera Journal, her music reveals that she is deeply attracted to this model of virility and bravery, as a woman proud of her beauty and her power over men.[1]

Samson, like many French Grand Operas, is laid out in five acts, but the work moves along more quickly than, say, Meyerbeer’s Les Huguenots. The five acts are grouped into three large “parts”: Act 1, Acts 2-3, and Acts 4-5. As in the Saint-Saëns (and the Bible story), the Israelites are presented as a population oppressed by the invading Pelistim. But Abimelech gets a bigger role here than in the Saint-Saëns: it is he, not the High Priest, who cajoles Delilah into seducing Samson. And here Samson, because of his love for Delilah, joins, for a time, the Philistine forces in fighting against various other peoples in the region. There are several additional characters, notably an Israelite turncoat, Micha, who betrays Samson and causes him to be captured.

The work moves at a stately but steady pace, often building scenes to rousing conclusions with many singers. There is little coloratura writing — ornamental, virtuosic singing that Raff presumably considered too superficial for the context. The orchestration is skillful and never overwhelms the voices.

As is common in French Grand Opera and similar works, the libretto gives many characters lots of words, sometimes sung simultaneously. This can sometimes be unintentionally comical, as in Act 1, Scene 4, when Micha publicly professes love for Delilah, declaring that he has betrayed the Israelites for her. Four sets of characters respond at once, each with different words: Delilah states her heart belongs to another; King Abimelech, her father, expresses frustration; the chorus of priests and male leaders sing about the mysteries of the heart; and the priestesses and Delilah’s women express hope that Baaltis will sway Delilah toward Micha. A more experienced composer might have allowed these groups to reply in sequence or perhaps omitted this formulaic passage entirely. One advantage of having a recording is that a listener can replay this section to focus on one group at a time.

Soprano Olena Tokar sings the role of Delilah in Samson.

Not surprisingly for a composer who would become renowned for his program symphonies and orchestral suites, the orchestral passages are particularly successful, such as a splendid march (over ominous drum-tapping) at the end of Act 2. This occurs just after a scene in which King Abimelech, having successfully persuaded (at least for the moment) his cherished daughter to give up her love for Samson, prepares to go off to war against Samson and his Israelite forces.

Likewise appealing is the “pastoral” (landschaftlich) Prelude to Act 3, for violin and orchestra, which points the way to the one piece by Raff that has been recorded more often than any other (by Itzhak Perlman, for example): his Cavatina for Violin and Piano, Op. 85, no. 3, published in 1862. The tuneful Prelude evokes the calm, luxurious atmosphere of King Abimelech’s palace grounds. We will soon meet Samson, now wearing Philistine soldier’s garb and with his long hair cut short (a bad decision!). It turns out that he has changed sides and is preparing to conquer further territories for the Philistines in order to secure Delilah’s love. By the end of Act 3, he will be overcome by Micha and some Philistine men, who tie him down and blind him. Acts 4 and 5 parallel more closely the Bible story, though here it is Delilah herself who will, disguised as a boy, lead him to the pillars, where he will bring the whole temple crashing down in an act analogous to what, today, might be called a suicide bombing.

Raff’s music is, throughout, immensely singable and often memorable; also ably harmonized, and varied in texture and style. Yet it almost never shows a distinctive profile. (Such has been my reaction to many of his other works that I have gotten to know, such as the aforementioned Lenore symphony, which misses much of the drama of Gottfried August Bürger’s famous narrative poem, by contrast to the highly dramatic setting by Anton Reicha.) Not surprisingly, there are some recurring themes: this is a device that Weber had already used in a few spots in Der Freischütz and that Wagner developed in a more thoroughgoing way in his operas from Lohengrin onward. Still, originality need not be the sole or ultimate criterion of merit. Samson is a much more gratifying work than one would suspect, given its sorry fate during Raff’s lifetime, and it makes me want to get to know more of his output.

The work had to wait until 2022 for its first performance ever, in Weimar (appropriately, or — given Raff’s break with Liszt — ironically). The recording was made under studio conditions shortly before the work’s staged premiere in Bern, Switzerland, on September 8, 2023, and it is fully professional, allowing the well-chosen singers — an international bunch (from Denmark, England, Ukraine, and so on) — to put the drama across effectively while always maintaining a solid core of tone. Tempos under Philippe Bach are well gauged and are often adjusted to suit shifts in the drama. The Bern chorus (Chor der Bühnen Bern) makes the most of its many moments, whether as Pelistim, priests/priestesses, male and female sacred prostitutes (kadeshim/kedeshot: more Bible-derived terminology), or Israelites. Recorded balances are excellent, with the fine orchestra never obliterating the singers. Even the chorus makes its resonant textures and heartfelt words audible (when Raff hasn’t made this impossible, as noted earlier).

All in all, this is a stirring example of a direction that opera could have taken in the mid and later 19th century if it hadn’t been hijacked, we might say, by the Wagnerian model of symphonic opera with freely declaimed vocal lines laid on top. Raff can now join the list of composers, such as (in France) Berlioz, Gounod, Saint-Saëns, and Bizet, who maintained a more traditional relationship between music and drama and created durable and effective works that (with the exception of two works: Faust and Carmen) deserve more attention than they received in their own day and ever since.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music and Senior Editor of the Eastman Studies in Music book series (University of Rochester Press), which has published over 200 titles over the past thirty years. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, and Classical Voice North America (the journal of the Music Critics Association of North America). His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here, lightly revised, by kind permission.

[1] Ralph P. Locke, Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 175-202, 348-52; and, in greater detail, my “Constructing the Oriental ‘Other’: Saint-Saëns’s Samson et Dalila.” Cambridge Opera Journal, vol. 3, no. 3 (November 1991): 261-302.

Tagged: "Samson", Bern Symphony Orchestra, Chor der Bühnen Bern, Christian Immler, Joachim Raff, Michael Weinius, Philippe Bach