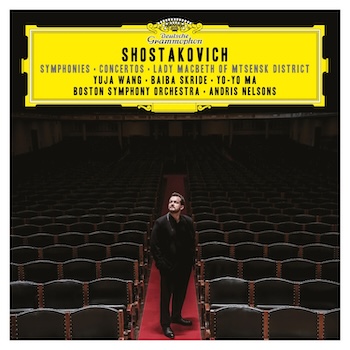

Classical Album Review: The BSO — Shostakovich, Complete Concertos

By Jonathan Blumhofer

There are some unfortunate misfires in a collection that, otherwise, has a lot going for it.

In its way, the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s Shostakovich series with music director Andris Nelsons on Deutsche Grammophon is the gift that keeps on giving. At first, just a survey of the Russian composer’s fifteen symphonies, the project was expanded to include the opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk and, later, the composer’s six concertos—two each for piano, cello, and violin.

In its way, the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s Shostakovich series with music director Andris Nelsons on Deutsche Grammophon is the gift that keeps on giving. At first, just a survey of the Russian composer’s fifteen symphonies, the project was expanded to include the opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk and, later, the composer’s six concertos—two each for piano, cello, and violin.

Along the way, assorted selections from Shostakovich’s catalogue of incidental music and more found their way into the project, which finally emerged in the form of a 19-disc box set that was released in late March. Though the results are sometimes variable, they’re not outside the norm for complete cycles of a single composer’s works by one orchestra and conductor. What’s more, the project stands as a major recorded accomplishment for the BSO.

The symphonic releases, several of which won Grammys, have all been reviewed in these pages; Lady Macbeth will get her turn in the coming weeks. For now, we can turn to the concertos, two of which—the ones for piano and cello—have also been released as stand-alone digital recordings.

Yuja Wang is the soloist in the former set, and she highlights a broad range of contrasts in each effort. The First, which dates from 1933, sounds rightly brash and acerbic in its outer movements; the pianist clearly relishes the music’s extroverted extremes. At the same time, the Lento broods with nuance, as does the short Moderato. BSO principal trumpet Thomas Rolfs delivers his snappy part with crisp precision.

The Concerto No. 2, which Shostakovich wrote a quarter-century later for his son, Maxim, involves writing that’s generally more reserved and refined. Wang’s approach to this score leans into big dynamic contrasts and massages a bit more reflection out of its pages than usual, especially in the Andante, which is beautifully focused and inward.

On the box-set disc, Wang’s contributions end there. But the digital release includes six short movements from Shostakovich’s op. 87 Preludes & Fugues that, one hopes, will be followed up before long by the pianist tackling that complete composition. To be sure, her playing of the preludes to Nos. 5 and 8, and both prelude and fugue Nos. 2 and 15, is nothing short of spectacular: clean, smartly directed, and terrifically light on its feet.

There’s no extra filler on the digital version of Ma’s disc, though it’s hard to imagine just what that might have been: both of Shostakovich’s cello concertos are profoundly darker in character than either of the keyboard works. Regardless, this is Ma’s second recording of the Concerto No. 1 and first of No. 2.

His account of the earlier score mines a bit more of its poetry than did his first go-around with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra in the early ‘80s. The outer movements are rhythmically tight and full of defiant character, yet it’s the Moderato that leaves the deepest impression: plaintive, reflective, and—at the end—ghostly. Richard Sebring’s several pivotal horn solos are each superb.

The Concerto No. 2, which dates from 1966, has always been among the most challenging of Shostakovich’s works to pull off. It’s bleak, brooding, dyspeptic stuff, and almost unrelentingly ironic. But Ma, Nelsons, and the BSO thread the needle here. They find warmth and humanity in the spare moments of its fragmented first movement and tease out the motivic unity and narrative logic of the latter two. The results are surprisingly affecting, especially given how hard this music can be to love.

Like the cello and piano concerti, Shostakovich’s violin concertos are each other’s polar opposite. The First has sat firmly in the repertoire since its 1956 premiere; the Second, from 1967, is, rightly or wrongly, more of an acquired taste.

The same might be said of violinist Baiba Skride’s take on the diptych. Granted, all parties involved have the notes in hand: there’s some terrific orchestral playing in No. 1’s Scherzo, and the soloist’s pure tone in high registers can be alluring.

Yet both Skride and Nelsons seem to be thrown by issues of tempo, which is surprising because Shostakovich provided metronome markings—quite a few of them, in fact—in both scores. If he had really wanted things to be twenty to thirty beats per minute slower than what he wrote, it stands to reason that the composer would have indicated as much. Ignoring such details, as happens here, is inadvisable, and the predictable results ensue: these are tedious readings that lack shape, style, and tension.

The Concerto No. 1 is spacious to a fault. No. 2 plods aimlessly. Skride’s occasionally husky, throaty tone and exaggerated glissandos seem to be trying to compensate for a shortage of meaty interpretive ideas; that tack quickly gets old. Nelsons, who’s awfully good in a lot of Shostakovich, seems at sea in both scores.

Given the strong recorded competition for both works (which includes Gidon Kremer’s Second Concerto with Seiji Ozawa and the BSO—also on the Yellow Label), these performances simply aren’t competitive. They make for an unfortunate misfire in a collection that, otherwise, has a lot going for it.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Andris Nelsons, Baiba Skride, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Deutsche Grammophon