Classical Album Review: World-Premiere Recording of Kurt Weill’s “Prophets” and Thomas Hampson in Weill’s “Whitman Songs”

By Ralph P Locke

One of the few conscious attempts by any major twentieth-century composer to articulate, and bewail, the effects of systematic and state-supported hatred and persecution of a people — any people.

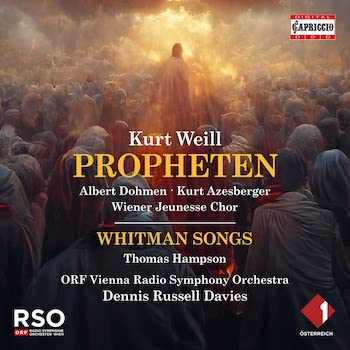

KURT WEILL: Propheten and Four Walt Whitman Songs

Albert Dohmen (Jeremiah, Voice of Solomon), Kurt Azesberger (Rabbi), Michael Pabst (Isaiah, and other roles), Gottfried Hornik (The Adversary—spoken role), Bernd Froehlich (Hananiah), Ursula Fiedler (Ruth).

Vienna Radio Symphony, cond. Dennis Russell Davies.

Capriccio 5500—65 minutes.

To purchase or to try any track, click here.

The Three Penny Opera will always be Kurt Weill’s best-known theater work, but The Eternal Road (1937) is by far his longest, partly because of the extensive spoken dialogue. This grand theatrical pageant was devised (in large part) and directed by the renowned Max Reinhardt, who was famous for stage extravaganzas in Austria, and who, by the time The Eternal Road got its first production (in New York), was spending much time in America and had begun his equally storied career as a Hollywood film director. (In 1938, after the Anschluss, he emigrated to the UK and then America and became a US citizen in 1940.)

The Eternal Road was a creative response to the horrifying situation that most Jews in Germany, Austria, and bordering lands to the east faced in the mid-’30s: these were millions of individuals whose very existence was threatened by the Nazis. Many were unable to find a country that would allow them to enter. Palestine, then under British control, had closed its ports to boats of refugees, as had the US.

The Eternal Road exists in versions bearing several different names. It was originally composed in German, just before Weill immigrated to America in 1935. The text was written by Franz Werfel, the renowned writer whose 1941 Song of Bernadette would become a best-seller and an award-winning film. Werfel remains famous for having been the third distinguished husband of Alma Schindler. (The first two were Gustav Mahler and the architect Walter Gropius.)

The work’s original name was Der Weg der Verheissung, which could be translated The Way of Promise, using “promise” in the sense of “the Promised Land,” a phrase for which one German equivalent is “das Land des Verheissung.”

The Eternal Road became its name in the world-premiere production, in English, which took place in 1937 in the auditorium of the Manhattan Opera House. (That building, much adapted during the intervening decades, is now known as the Manhattan Center.) The skillful translation was by the noted novelist and social commentator Ludwig Lewisohn. The elaborate production, featuring a large and remarkable cast, was greeted with great acclaim and ran for an astounding 153 performances, after which the work sank into oblivion for over half a century.

A scene from the 1937 production of Kurt Weill’s The Eternal Road, Act II. Photo: The Kurt Weill Foundation of Music

This massive work (in either of its primary versions: Weg and Road) intertwines two distinct threads: stories from the Bible (that is, from what Christian tradition calls “the Old Testament”) and the mounting Jewish-refugee crisis of the mid-’30s. The stage is split into five levels associated with different eras — and with the process of traveling to a safer place, as many biblical characters and real-life refugees try to do.

Since the ’90s, various shortened versions have brought Weg /Road, in whole or part, back onto the stage and into the concert hall. Some productions have been in German, others in English. Some consist mainly of musical numbers, omitting or greatly reducing the narration and spoken dialogue. Most attempt to give a sense of the work as a whole, even if selectively. Such is the case with the recording of English-language “highlights” (to quote the CD cover) on Naxos conducted by Gerard Schwarz and featuring such noted soloists as Constance Hauman and James Maddelena. That recording lasts 73 minutes. Much more complete, though again with greatly condensed spoken passages, is the version created by Edward Harsh and entitled The Road of Promise. (That version, when done in German, is called Die Verheissung.) The first performances of Harsh’s version (which led to a recording) were at Carnegie Hall in 2015, under conductor Ted Sperling. The cast included some remarkable young singers and some bigger names (e.g., Anthony Dean Griffey and Mark Delavan).

All of this leads to Propheten, the recording that I am reviewing here! Propheten consists of the final (fourth) act of the original and fullest version (that is: Der Weg der Verheissung). This act was jettisoned before the 1937 premiere (The Eternal Road), and so Weill never orchestrated it. In 1998, when the recording was made, this fourth act had never before been performed or recorded. It includes parts for three recent (non-biblical) characters — a Rabbi, a non-believing man called the Adversary, and the latter’s hopeful thirteen-year-old son — who also appear at various points in the three acts of The Eternal Road. But, primarily, it features Isaiah, Jeremiah, and other characters from the “prophets” books of the Bible.

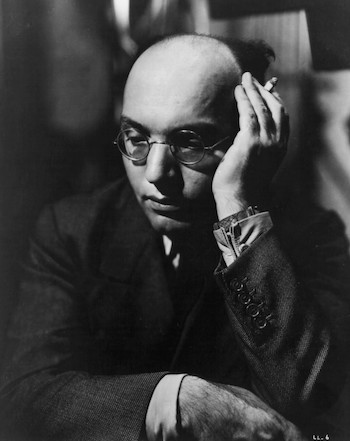

Composer Kurt Weill. Photo: Wiki Common

Certain of the texts, including some psalms, will be familiar to people who know their Bible, or their Handel and Vaughan Williams (“Comfort ye, my people!”; “O clap your hands, all ye peoples”). Weill’s music casts fresh light on these words, creating a memorable new fusion.

Whereas The Eternal Road — in its 1937 version — varies greatly in style, including some bittersweet numbers with simple tunes (along the lines of “Ach bedenken Sie, Herr Jakob Schmidt,” from Mahagonny), this “lost” fourth act is grim and intense. In short, it feels more like a traditional oratorio, less like a mashup of Broadway musical and historical pageant.

Propheten (German for, simply, “Prophets”) is the title that musicologist David Drew created for the performing edition of the nearly unknown Act 4 for use in concerts. Weill’s piano accompaniment was orchestrated by the renowned Israeli composer-conductor Noam Sherriff. Propheten includes a part for narrator to help us imagine what would have been apparent if the act had ever been brought to the stage.

To provide a satisfying ending, Drew borrowed the movement for the chorus and the Rabbi that ended Act 3 of The Eternal Road, a gratifying choice as it shows Weill at his most masterful. You can see how effective it is by comparing it to Antal Doráti’s opera about the prophets Elijah and Elishah, entitled Der Künder (The Herald), based on a text by the philosopher Martin Buber. Though that work is otherwise powerful and insightful, its finale becomes platitudinous in its reach for grandeur. (See my review here.)

Less wisely, Drew decided to begin Propheten with the long-beloved Zionist hymn Hatikvah (which eventually became Israel’s national anthem). He selected the forceful orchestral arrangement of it that Weill made for the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1947 during the lead-up to the UN’s vote that ended the British protectorate of Palestine. But Der Weg/The Road was very much a cultural product of the ’30s, not the late ’40s (much less the 2020s): a plea for millions of European Jews to be admitted to any country, before time ran out.

As such, Der Weg/The Road, and thus also Propheten, remains resonant as one of the few conscious attempts by any major twentieth-century composer to articulate, and bewail, the effects of systematic and state-supported hatred and persecution of a people — any people. I can imagine a production of it that would emphasize its universal applicability, much the way that better-known stage works (such as Madama Butterfly) have been creatively reimagined, though of course with varying success, to speak to present-day concerns and values.

The recorded performance of Propheten that we have here (that is, the largely forgotten Act 4 of Der Weg der Verheissung), from the belated world premiere in Vienna in 1998, is capable, with the singers all steady in tone, something that cannot be said of certain otherwise highly distinguished male singers on the Sperling recording of The Road of Promise. (By contrast, the female singers there are young and admirably fresh-sounding.)

The various actors and singers who are assigned spoken passages are full of character and point, without ever hectoring the listener. It helps that they are all native German-speakers. Unfortunately, by contrast with the Schwarz recording of significant excerpts from The Eternal Road, there is less attempt at differentiating the characters that we are hearing, such as the Seller of Idols. (Several short passages are included in both recordings, enabling direct comparisons.)

More generally, the conductor, Dennis Russell Davies, shows little sense for dramatic pacing: everything feels “correct” and well managed, but the surging flow and affectionate melodic shaping that Gerard Schwarz brought to Naxos’s excerpts from the 1937 translated version (The Eternal Road) are sorely lacking here. Davies has an estimable reputation as a conductor, not least of modern works: he co-founded the renowned American Composers Orchestra. But I wonder if he is simply the wrong person for works of a dramatic nature. His recent recording of Reicha’s creepy Lenore cantata felt dutiful and noticeably less atmospheric and exciting than the previously available ones (see my review here).

Baritone Thomas Hampson. Photo: Jimmy Donelan

Still, this is the only recording of the final “lost” act of Werfel and Weill’s Der Weg der Verheissung that has been made thus far. We are lucky that it finally got released so we can hear the music and think about its relationship to the carefully chosen words. I will cherish it, while still awaiting a version of the complete work sung, as intended, in German (and without the anachronistic insertion of “Hatikvah”). After all, Weill was a master at text-setting, as anybody who knows The Three Penny Opera, Happy End, or Mahagonny in recordings that use Brecht’s original words will agree. Ideally, the spoken passages would be declaimed on such a recording (as on the present one); or, if omitted, then printed in the booklet.

The disc closes with a stunning performance of Weill’s Four Walt Whitman Songs (composed 1942-47) by Thomas Hampson, in the version orchestrated by Weill and, for one song, by Carlos Surinach. The song cycle was recorded at the Salzburg Festival in 2001, when the great baritone was at the peak of his art. Here, conductor Davies seems more at home.

The booklet contains excellent essays plus the sung and spoken texts, all in both German and English. The reliable translation of the Werfel text is by Gillian Ward and David Drew.

I would like to mention that certain other major works envision one or another of the biblical prophets, including Mendelssohn’s Elijah, Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s violin concerto I profeti (The Prophets), and Bernstein’s Symphony No. 1: “Jeremiah” (whose movement titles are Prophecy, Profanation, and Lamentation). Someone could write an interesting essay comparing these and other such portrayals. The German-Jewish composer Ferdinand Hiller (1811-85) crafted a wonderful Jeremiah oratorio, in German, that was much praised by Schumann and oft-performed for several decades: its title is The Destruction of Jerusalem (1840). A vivid recording, featuring the eloquent baritone Daniel Ochoa, was released in 2012.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.