Music Perspective: The Context of Wadada Leo Smith’s 12 String Quartets

By Steve Elman

Wadada Leo Smith is among the most prolific composers of string quartets in the modern era, the only Black composer to have written so many, and one of the most adventurous writers of quartets in terms of his notation system and the distinctiveness of his musical language.

In my review of the 2022 release of string quartets Nos 1 – 12 by Wadada Leo Smith, I noted their significance as an important cycle in string quartet repertoire and as the most significant body of work for string quartet ever written by a composer whose primary identity with the public is as a jazz musician.

But there’s a lot more to the story, as I learned in my research over the past few months.

Like his contemporaries in the Chicago School of the jazz avant-garde — Anthony Braxton, Henry Threadgill, Roscoe Mitchell, and others who emerged from the Association for the Advancement of Creative Music, Smith seeks to find ways for his music — whether it is heard as jazz or classical or as music without boundaries — to sound fresh and of the moment, even as it evidences the profundity of considered thought. These qualities are amply manifested in the quartets.

In this post, I’d like to delve into the Why and How of these pieces, because the context in which Smith created them is interesting in itself, and because the Why and How illuminate the composer as a person and as a creative artist.

A listener who has begun to explore the Smith quartets will probably ask: Where do they come from?

Smith has been direct about his inspirations as a writer of string quartets. He says he began writing for the medium in 1965, after hearing Ornette Coleman’s “Dedication to Poets and Writers,” which was played at Coleman’s 1962 Town Hall concert in New York City and released on ESP-Disk’ in 1965.

This short work for string quartet is Coleman’s first classical piece, one of only three works he is known to have written for string quartet, and the first through-composed classical work by a composer whose primary association for the public is as a jazz musician (all of Ellington’s hybrid pieces involved improvised solos for himself or members of his orchestra, and Mingus’s through-composed work was yet to come). “Dedication to Poets and Writers” is completely coherent within the classical vernacular and deserves rediscovery by string quartets with a passion for new music. The long lines of melody that thread through it seem like they could be transcriptions of Coleman’s own saxophone solos from the period. This is clearly Coleman’s music in Coleman’s voice, transferred to another medium, and a worthy inspiration to a young performer-composer.

Smith says he was also inspired by Bartók’s six string quartets. These works are composed of brief kernels of notes that are transformed ingeniously into complex fabrics of sound that follow some of the established forms of classical music – but in a very personal way. Smith does not construct his music as Bartók did (more about this below), but Smith’s language is perhaps closest to Bartók’s among the top rank of classical composers, and those who love Bartók will find Smith’s language congenial.

Smith also cites the late Beethoven quartets, Debussy’s quartet, and the string quartet writing of John Lewis (whose “Sketch,” with the Beaux Arts String Quartet, was issued on Atlantic in 1960) as other influences.

These examples, from masters of the form, are only works that Smith particularly admires. His quartets are not “in the style of” any other composer. They are a logical progression for an artist whose work throughout his career has been an adventure in combining spontaneous and planned elements.

Many of his other works feel and sound like jazz. But this is adventurous and ground-breaking jazz with profound ambition as I noted in a post about his four “Chicago Symphonies.” They are not written for orchestra, but for what looks, on its face, to be a standard jazz quartet — trumpet, saxophone, bass and drums. In contexts like these, Smith is a warm and supple soloist whose admiration for Miles Davis is obvious — but (just as in his string quartets), Smith is standing on the shoulders of his predecessors, not trying to emulate them.

It may come as a surprise that Smith did not hear Shostakovich’s landmark cycle of fifteen quartets until 2013, almost 50 years after he started writing his quartets and when he had already completed eight. Smith’s language was fully formed by that time, but he has embraced the Shostakovich works with enthusiasm since hearing them. In a July 2016 interview he said, “In my studio right now I have [the scores of] every one of the string quartets that Shostakovich composed. And the late Beethoven string quartets. And Béla Bartók’s six string quartets. And Villa-Lobos’s seventeen string quartets.”

Comparison between Shostakovich and Smith is probably inevitable. It is instructive, especially if Shostakovich’s works are your paradigms of the medium in the twentieth century.

Shostakovich’s sound-world is not like Smith’s. His quartets constantly seize a listener’s attention with their strong musical motifs and song-derived earworms. He remains concerned with traditional classical forms even when he comes close to breaking their bonds. His quartets are also suffused with an intense personal drama; the composer is struggling to suggest feelings that are imprisoned deep within his own heart. Smith’s language is beyond tonality, more abstract and less tuneful than Shostakovich’s, and he expresses no such angst about his life or his world.

Shostakovich’s movements are more private than public, like diary entries that have come to light posthumously. Smith’s are more public than private, like readings of poems that express his reflections on his life and his hopes for a better world.

Shostakovich’s cycle comes to a dark end, as he stares into the abyss of eternity in the fifteenth quartet with a sense that he is about to enter a place of nothingness. Smith’s greater quartets have all been written after the age that Shostakovich died. In his pieces there is no sense of the darkening hours in his days; instead, he is glorying in a rich sunset.

Wadada Leo Smith. Photo: Jimmy Katz.

If Shostakovich’s work can be heard as an organic product of the Soviet era in Russia, Smith’s can be heard as an organic product of late-twentieth-century American optimism. If Shostakovich is quietly celebrating the persistence of the creative spirit over a world of repression, Smith is exuberantly celebrating the vitality of a society where creative personal expression is moving forward, despite the obstacles in its way.

Shostakovich dedicated his Quartet No. 8 to “the victims of fascism and war” and six of the others (collectively and individually) to the members of the Beethoven Quartet, who premiered thirteen of the works. Otherwise, he allows his string quartet music to stand as pure sound for the listener to interpret.

At the age Shostakovich died, he had written fifteen quartets. At the same age, Smith had written only six, in which he tested himself and the form to see what he could accomplish. The quartets Smith has written after the first six, in the past decade-plus — after his 70th birthday — are new testaments in a more confident language, his more mature works in the idiom. He apparently has found the medium so rewarding that he continues to add to his cycle.

Smith’s titles show that his music is at least a partial expression of his reverence for his cultural heroes. It is clear from the people named in his first twelve quartets that Smith is well aware of the challenges that came with widening the horizon of freedom in America. His works are no less optimistic because they recognize that struggle. Quartet No. 5 is dedicated to Haki Madhubuti, a poet who co-founded the Chicago-based Third World Press, an outlet for Black literature. Quartet No. 7 is inscribed “In Remembrance of Dorothy Ann Stone” – Stone was a flute virtuoso who founded a pioneering new-music group in Los Angeles, the California EAR Unit. And there are ten movements named for Smith’s predecessors in music, including five pioneering Black composers of classical music and five titans of jazz, blues, and gospel.

In my review, I noted that the titles Smith has given to some of the quartets, including the people he names as honorees in individual movements, should not be considered keys to understanding the compositions. A listener should engage directly with the music first, see how it makes them feel, and only then reflect on what additional resonances the titles or names may suggest.

Here are a few comparisons of Smith’s titles with the music as it is heard on the new set.

The title of quartet No. 6 (“Taif: Prayer in the Garden of the Hejaz”) evokes the Middle East and suggests a connection to Smith’s Muslim faith. Still, the music seems to exist somewhat independently of either. “Garden of the Hejaz” refers to Al Bahah, a town in the Hejaz region of Saudi Arabia that has grown around a hilltop village with a 400-year history. The music of No. 6 is not conspicuously Middle-Eastern, and its tone is not particularly contemplative or prayerful. It has an unusual and distinctive color, thanks to a trio of instruments playing mostly in contrast with (but subordinate to) the string quartet — trumpet and piano each have prominent roles here, with support from a percussionist. There is a moment of particular eloquence from Smith himself, who plays the trumpet part, and this may be analogous to the prayer in the title. But a listener certainly does not need the title to hear the eloquence in the playing.

No. 10, the one-movement quartet named for Angela Davis, is eloquent, poetic, meditative, and declamatory by turns. It even includes a little folk-tune-like motif that is rare for the cycle as a whole. I have the impression that the music is more of an homage to Davis than a portrait of her.

No. 11 may be particularly notable because of the people Smith names in eight of its nine movements, ranging from people in his own biological family to Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong, and Black classical composer Alvin Singleton. It is the longest of the quartets, taking more than 90 minutes to perform. But the names, and the fact that so many of the people are members of Smith’s own family, do not make this his “Family Quartet.” There is a distinctive motif that returns in each movement — long unison chords played by all of the four strings. In the central movement, titled “At the Heart’s Core, Knowledge,” this motif blossoms into a long passage of unison melody that is striking and very distinctive — one of the highlights of the entire quartet cycle. But is Smith suggesting some kind of confluence among all the people he names? I don’t think so.

Even in Quartet No. 1, in which each of the four movements is named for a pioneering Black classical composer, the naming does not pay off in direct references to the four composers’ styles. Each of them wrote in modern classical idioms, and each had some personal connection to the jazz tradition — a trait Smith shares with them. But the connections may stop there.

- Ulysses Kay, for whom the first movement of No. 1 is named, composed mostly in a neo-classical style that was tonally adventurous. He had a gift for melody. Smith’s movement has some striking features, including a passage of heavily massed sound that suggests all of the quartet’s players playing as many of their strings as possible simultaneously.

- T. J. Anderson, the composer named in the second movement, writes open-hearted modern music that is eclectic and innovative, with some usage of non-traditional scoring and organizational techniques. This movement has lots of fire and excitement, with sudden bursts and interjections.

- Hale Smith, named in the third movement, was a Midwesterner who wrote modern music with an open spaciousness that evokes the big skies of the heartland. This movement is long-breathed, but filled with tension.

- The music of George Walker, for whom the last movement is named, was harmonically modern, crafted with elegance and grace. This movement is a series of passionate songs. The movement begins with a beautiful solo cello statement which evolves into lyrical lines played by each member of the quartet, sometimes in duet, sometimes as a group, sometimes independently, sometimes in near-consonance, almost always songful.

Strictly speaking, only seven of these twelve pieces are string quartets in the traditional sense — written for only two violins, viola, and cello. Four of the others bring in additional instruments, and these augmented quartets are notable for the variety of ways in which Smith integrates the other timbres. However, even in each of these, the traditional quartet remains the principal voice.

These “ringers” should be considered true string quartets, but quartets in which the standard ensemble is decorated, juxtaposed, or integrated with other instrumental colors. (In fact, the idea of a “string quartet” having additional instruments or voice as coloring elements is not new with Smith. Arnold Schoenberg included voice in his second quartet, and Australian composer Peter Sculthorpe added didjeridu to three of his.)

RedKoral Quartet. Left to right: Ashley Walters, cello; Shalini Vijayan, violin; Andrew McIntosh, viola; Mona Tian, violin. Photo: R.I. Sutherland-Cohen.

Smith’s No. 4 is written for the traditional quartet plus harp, which is played in this recording by Los Angeles-based harpist Alison Bjorkedal. The harp has a decorative role in this piece except for a short solo interlude that serves as the fourth movement. Overall, the work has a strong sense of forward motion and passion. I particularly like the third and fifth movements.

No. 6, “Taif: Prayer in the Garden of the Hejaz” is written for the traditional quartet and a contrasting trio of trumpet, piano, and percussion (traps without snares [played with mallets], cymbals, marimba, and a few little percussion instruments). The guest artists in this recording are Wadada Leo Smith himself playing trumpet, Anthony Davis (a Pulitzer Prize-winning composer in his own right) playing piano, and Lynn Vartan handling the percussion parts. Once again, the string quartet has the primary role. Each of the two ensembles is given an independent statement in the first two sections. In the third, the strings begin, and the augmenting trio gradually takes over and gets the final words. In the final section, the strings have long opening and closing statements, juxtaposed with a very short fanfare-like section from the augmenting trio about a minute and half before the end of the movement.

The seventh and eighth quartets are named for species of desert succulents, and both include guest artists. It may be a coincidence that the work with a Los Angeles-based guest is named for a Western plant and the work with a New York-based guest is named for an Eastern one, but the symmetry is pleasing.

No. 7, “Ten Thousand Ceveus Peruvianus Amemevical (In Remembrance of Dorothy Ann Stone)” is written for the traditional quartet with amplified acoustic guitar, played in this recording by Stuart Fox, a Los Angeles-based musician who has a very broad range of repertoire, from Renaissance lute to new music. The composition sets up a constant conversation among the five instruments, with occasional solo spots for the guitar.

No. 8, “Opuntia Humifusa” is written for the traditional quartet with trumpet (again in this recording played the composer) and wordless voice, sung here by baritone Thomas Buckner, a New York-based singer who has been a leading light of new music for more than 40 years. He is also a former member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Music (AACM) in Chicago, where Smith began his composing and performing career. Buckner’s voice is an interesting compromise between wind and string instrument — he favors long tones, and holds pitch well without vibrato. He draws on a few extended techniques in this piece, but he uses mostly pure tones, produced without operatic show or jazz inflection. The music of No. 8 is kaleidoscopic, with the strings in the spotlight most of the time, but there are solo interludes for the voice and the trumpet, and a short duet for voice and trumpet without the strings.

Finally in this set, there is Quartet No. 12, which is unique in Smith’ s work so far, and unusual for any composer — it is a quartet for four violas, led by RedKoral’s violist Andrew McIntosh. This is a rare turn in the spotlight for a “subordinate” string instrument, which becomes an evocative celebration of all the rich sonorities it can produce.

Quartet No. 13, which is as yet unrecorded, is also reportedly an augmented work, including soprano voice.

Smith described the challenges RedKoral and the other musicians faced in bringing his scores to life when he spoke in 2018 with violist Doyle Armbrust of the Spektral Quartet:

My scores are essentially non-metric, and a full page is a ‘bar’ with no down and up beats. Part of the horizontal flow of the music comes from the score but within [a performing] ensemble the leadership shifts from person to person as the decisions for continuity keep changing from page to page. . . . Even in cases where there are clearly written lines, the artists . . . use their imagination to construct or shape the music lines, and therefore its flow.

In July 2022, Seth Colter Walls filled out this concept and its challenges in an article on the quartets in the New York Times: “Players use a ‘constructed key’ of Smith’s design when interpreting and creating their responses to the symbols and colors on each page. Some of his quartets require players to move back and forth between traditional notation and Ankhrasmation pages, within a single movement. Navigating this takes practice and dedication.”

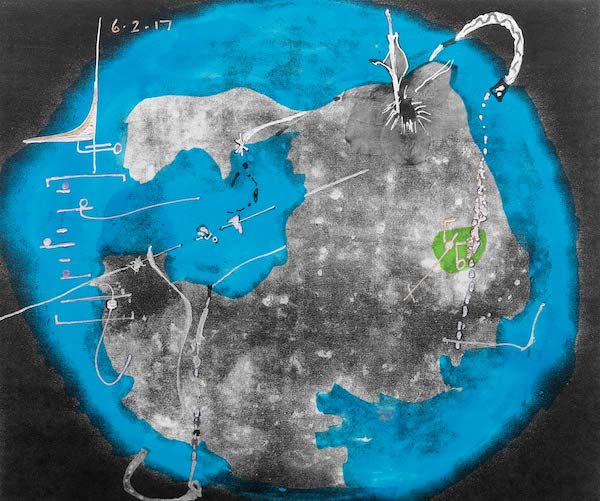

Walls’s article also includes a reproduction of a page from the ninth movement of Smith’s Quartet No. 11, the movement dedicated to his father – “Red Autumn’s Gold (For Lucius G. Smith).”

Anyone interested in the How of Smith’s music should have a serious look at the image there, and at the Ankhrasmation pages of his website, where more pages are reproduced. Smith’s site also offers four pages of scores from his “Seasons” symphonies, along with descriptive notes that show what the visual images represent and provide specific directions to the performers.

An Ankhrasmation page from Wadada Leo Smith’s Symphony No. 1, Spring.

(Note: The “Seasons” symphonies are not pieces for orchestra. In a 2016 performance at The Lab in San Francisco, the instrumentation was trumpet (played by Smith himself), piano (played by Anthony Davis), harp, percussion, and electronics. This link provides a 10-minute video excerpt of that performance.)

Despite all the titles and the technical challenges to the players, the sound of the music and its impact are ultimately the only things that matter to the ordinary listener. And this reality presents important challenges to the lasting influence and continued performance of Smith’s music. When the composer is gone, the method to interpret an Ankhrasmation score will have to be transmitted to young musicians orally, by someone who knows Smith’s systems intimately — as I see it now, that torch would be most appropriately carried by one of the members of RedKoral. But for those at more distance from the music, those who know it from recordings alone, performance will mean transcription of a recording as a guide to interpreting the score — which might be a legitimate act from Smith’s point of view, but it also would sacrifice the personal interpretive element that would bring the music to life in the way the composer desires.

So hear the music in its time, now, vitally interpreted by living artists under the guidance of a living composer. And look forward to its next chapters.

MORE:

I am profoundly grateful to my old friend and radio colleague Doug Briscoe for providing his invaluable musicological advice in the final edit of this essay.

A number of sources illuminate how Smith has modified quartets 9 – 12, and provide a preview of No. 13.

Some insight into the original inspiration of Quartet No. 9 comes from the Hartford Jazz Society newsletter in 2017 in a preview of a RedKoral performance in Wadada’s “CREATE Festival in New Haven, April 2017, when he was on the faculty at Yale.

“No. 9” features four movements dedicated to female African-American pioneers in music and the Civil Rights movement (Ma Rainey, Marian Anderson, Rosa Parks, and Angela Davis).

Two movements from the original idea remain in the final version of No. 9, and they have a completeness that makes them ideal companions. The Angela Davis portion may have been expanded or transferred to independent status in the one-movement Quartet No. 10. The Rosa Parks music may have been transformed into or included within his Pure Love: an Oratorio of Seven Songs (released on TUM, 2019) which includes RedKoral among the performers — but there are no pure string-quartet movements as such in it.

A 2017 article by Ted Panken includes a reference to a piece called “Quartet No. 10”, with Anthony Davis on piano, performed on April 20, 2017 at The Stone in NYC – but this is clearly not the same piece as the one given the final title of No. 10. It is not known whether that music was incorporated into the finished version of No. 10, which does not include piano.

In 2022, new subtitles were added for movements 4 and 6 of Quartet no. 11, the movements naming Smith’s daughters, as shown in a program for a performance by RedKoral at LAXART, May 2022:

- Kashala Kiom Smith (Two Stars in a Golden Sky and the Book)

- Sarhanna Kabell Smith (A Reddie Copper Sky)

Some insight into the original inspiration of Quartet No. 12 comes from the Hartford Jazz Society newsletter in 2017 which includes this note: “Sunday’s concert begins with Smith’s 12th String Quartet, the “Pacifica,” which was premiered at the 2016 Vision Festival and was written for four violas with Smith’s trumpet and electronics.”

Avant Music News also includes a description of a performance of the same version of No. 12.

In the final version of No. 12, the 4-viola concept and the “Pacifica” name remains — now attached only to the second movement — but Smith’s trumpet and the electronic effects are gone. In addition, there is a now a movement named for Billie Holiday.

Some indication about the character of Quartet No. 13, which has not yet been recorded, comes from a LAXART program in May 2022, previewing the quartet’s West Coast premiere. The performers are shown as Karen Parks, soprano, with the RedKoral Quartet. The movement titles are also shown:

I. The Dark Lady of the Sonnets (Text by Amiri Baraka)

II. Billie Holiday, 1915-1959: The Dark Lady of the Sonnets

III. Fred Hampton: I am a Revolutionary for Freedom, Liberty and Justice

IV. Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party 1964 / Black Panther Party 1966 – Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, Bob Moses, Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale, Elbert Howard

Wadada Leo Smith. Photo: Michael Jackson.

Finally, some perspective on Wadada Leo Smith’s place in string quartet history:

Smith, who turned 81 in December 2022, begin writing his first quartet in 1965 (although it took 17 years for that work to reach its final form). He began his second quartet in 1969, and it reached its final form in 1980; this was the first quartet that he declared “finished.” As of this date, his cycle of quartets now stands at 17.

With 1965 as the starting date, he has been writing for the medium for 58 years. With 1980 (the year his second quartet was completed) as the starting date, he has been fully engaged in writing quartets for 43 years. He is among the most prolific composers of string quartets in the modern era, the only Black composer to have written so many, and one of the most adventurous writers of quartets in terms of his notation system and the distinctiveness of his musical language.

The writing of ensemble pieces for early viols may have begun as early as the mid-1500s, although these early works would not sound like the string quartets we know today. For hundreds of years, pieces for four stringed instruments, were most often “occasional music”– background music or light music for events held by the nobility and the wealthy.

Serious and significant works in the form began to be produced in the late 1700s by Franz Josef Haydn — as he did in so many other genres, Haydn grew in his prowess of composing these pieces over time, and he brought the form to maturity as he did so. He wrote his first string quartet around 1760 and his last in 1803, a span of more than 40 years, over which time he wrote some 77 works for string quartet.

Perhaps the most prolific composer of string quartets in history was Italian composer Giuseppe Cambini (1746 – 1825?), who started writing them about 1772, and produced at least 149 in about 50 years.

Other prolific composers of string quartets in the classical era include Johann Albrechtsberger (1736 – 1809), who wrote 73; Paul Wranitzky (1756 – 1808), who wrote nearly 60; Ignaz Pleyel (1757 – 1831) who wrote some 94 quartets over 60 years of composing; Franz Krommer (1759 – 1831), who is credited with 100 or more; and Louis (Ludwig) Spohr (1784 -1859), who wrote 36.

The first masterpieces come with the late quartets of Haydn. In his wake, Mozart and Beethoven set new standards of brilliance. Mozart completed his first string quartet in 1770 and wrote the 23rd, his last, in 1790, in a span of about 20 years, at an average of more than one quartet a year. Beethoven began his first quartet in 1798 and wrote the 16th, his last, in 1826, a span of 28 years.

Then the floodgates open. Hundreds of quartets (maybe more than a thousand) were produced in the 19th century by composers at all levels of talent and skill, and the 20th century saw many more.

Franz Schubert was among most prolific and distinguished writers of the 19th, with 15 composed over a span of 16 years or so.

In the modern era, composers have broadened the language of the form and the ways in which their quartets were written. Some of the boldest experimenters were Arnold Schoenberg (1874 – 1951) who wrote 5, four of which utilize his serial or 12-tone system, and John Cage (1912 – 1992) and Witold Lutosławski (1913 – 1994), who each wrote only one, employing chance elements in their compositions.

Here are some other notable string quartet writers of the modern era, ranked by the number of quartets completed as of this date. It is worth noting that, unlike Smith’s, nearly all of their quartets utilize standard notation.

Northern Irish composer Ian Wilson (1964 – ) wrote his first string quartet in 1992. He has written 21 so far in over 31 years.

Danish composer Vaqn Holmboe (1909 – 1996) wrote his first in 1926 and his last in 1995, producing 21 works over 69 years.

French composer Darius Milhaud (1892 – 1974) wrote his first in 1912 and his last in 1973, producing 19 works over 61 years.

Serbian composer Aleksandra Vrebalov (1970 – ) wrote her first in 1995. She has written 18 so far over 28 years.

Australian composer Peter Sculthorpe (1929 – 2014) wrote his first in 1945 and his last in 2010, producing 18 works over 65 years. Several of his quartets add the Aboriginal instrument the didjeridu to the standard ensemble.

Brazilian composer Heitor Villa-Lobos (1887 – 1959) wrote his first in 1815 and his last in 1957, producing 17 over 42 years.

English composer Robert Simpson (1921 – 1997) wrote his first in 1945 and his last in 1996, producing 16 works over 51 years.

Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich (1906 – 1975) wrote his first in 1938 and his last in 1974, producing 15 over 36 years.

English composer Peter Maxwell Davies (1934 – 2016) wrote his first in 1961 and left his last unfinished at the time of his death, producing 14 works over 55 years.

English composer David Matthews (1943 – ) wrote his first string quartet 1969. He has written 14 so far over 54 years.

Russian composer Nikolai Miaskovsky (1950 – 1881) wrote his first in 1907 and his last in 1949, producing 13 over 42 years.

English composer Elisabeth Lutyens (1906 – 1983) wrote her first in 1939 and her last around 1979, producing 13 over 40 years.

English / Irish composer Elizabeth Maconchy (1907 – 1994) wrote her first in 1933 and her last in 1983, producing 13 over 40 years.

Hungarian composer Béla Bartók (1881 – 1945) wrote his first quartet in 1909 and his last in 1939, producing 6 over 30 years.

Armenian-American composer Alan Hovhaness (1911 – 2000) wrote his first in 1936 and his last in 1976, producing 5 over 40 years.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included 10 years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

Tagged: Ankhrasmation, RedKoral, RedKoral Quartet, Steve Elman, String Quartets, String Quartets Nos.1-12, TUM, Tum Records