Book Review: Selma Blair’s “Mean Baby” — Genuine Self-Reflection

By Henry Chandonnet

Actress and MS advocate Selma Blair’s memoir is not just another celebrity tell-all, filled with smarmy self-congratulation.

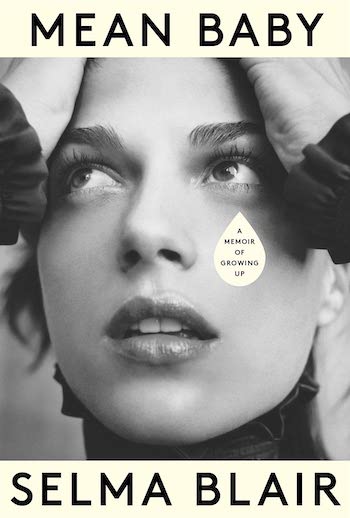

Mean Baby: A Memoir of Growing Up by Selma Blair. Knopf, 303 pp, $30.

It is rare to come across a celebrity memoir that isn’t about filling column inches in tabloids, stuffed with flimsy half-stories, listicles, and flickers of pseudo-gossip. Do any celebrities, from reality TV stars to political magnates, publish memoirs that are worth reading? What usually hits the shelves are little more than cash-grabs that inevitably betray the genre because they are less about evaluating personal behavior than serving as self-help manuals for wannabe household names. They OD on overconfidence because it is the triumph of ego over luck. So it is a pleasure to report that Selma Blair’s Mean Baby rises above the dismal mean. Where others are lifeless excursions into hubris, Mean Baby exudes an air of genuine self-reflection, a grounded modesty.

It is rare to come across a celebrity memoir that isn’t about filling column inches in tabloids, stuffed with flimsy half-stories, listicles, and flickers of pseudo-gossip. Do any celebrities, from reality TV stars to political magnates, publish memoirs that are worth reading? What usually hits the shelves are little more than cash-grabs that inevitably betray the genre because they are less about evaluating personal behavior than serving as self-help manuals for wannabe household names. They OD on overconfidence because it is the triumph of ego over luck. So it is a pleasure to report that Selma Blair’s Mean Baby rises above the dismal mean. Where others are lifeless excursions into hubris, Mean Baby exudes an air of genuine self-reflection, a grounded modesty.

Those who ask “who is Selma Blair?” are not alone. In fact, Blair recognizes that her notoriety comes from supporting roles. Her industry cred lies in her “second on the call sheet” resumé. Blair writes, “My career was on the rise, but I had a hunch I was not going to be a leading lady. I was a supporting player. That was who I knew how to be.” You probably know her biggest hits. Blair played Cecile Caldwell in the iconic ’90s teen drama Cruel Intentions, an Upper East Side adaptation of Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses. That movie also launched a friendship between Blair and Reese Witherspoon, a bond that would bring her to her next famed project, playing Vivian Kensington in Legally Blonde. Blair also starred in Guillermo del Toro’s fantastical Hellboy II, and was the first actress to grace the cover of Italian Vogue. Now, Blair spends most of her time working as a public advocate for those suffering from multiple sclerosis (MS).

Blair boasts a prolific resumé of Hollywood experience, but most of Mean Baby centers on her personal life and trials. The book’s subtitle underlies this: “a memoir of growing up.” Blair investigates her childhood in significant detail, touching on her problematic relationship with her mother, early alcoholism, and the trauma of sexual assaults. Blair never wallows in the pain, writing with the poise and grace it takes to remain emotionally distanced. For example, here she reflects on her rape: “I wish I could say what happened to me that night was an anomaly, an isolated incident. But it wasn’t. I didn’t think of them as traumas. I have been raped, multiple times, because I was too drunk to say the words ‘Please. Stop.’” These words are shocking because there is no attempt at self-pity. This is not a “woe is me” tale in which a horrid childhood and adolescence is gloriously overcome with fame as the reward. Blair’s writing is reflective rather than melodramatic. This is an instructive meditation on mistakes made.

Blair is so good at writing about personal strife that the industry tittle-tattle portion is surprisingly lackluster. This is ironic, given that juicy showbiz stories are the reasons many readers pick up celebrity memoirs. What was Reese Witherspoon like, or Carrie Fisher? The stories here are welcome, but they lack the depth and complexity of Blair’s self-examination. She is much better at analyzing herself than others. Luckily, the Hollywood tales only make up a short section in Mean Baby, and Blair soon turns back to her personal life and relationships. Once the book moves on to describe Blair’s journey through motherhood and an MS diagnosis the narrative becomes stronger.

Throughout Mean Baby, Blair references her lifelong love for the writing of Joan Didion, and that influence might offer a key to the memoir’s power. Like The Year of Magical Thinking, this is a skillfully restrained evaluation of agonizing intimate experiences. Maybe she hasn’t “conquered” her traumas, but Blair has articulated them clearly and cleanly, and that in itself is a kind of triumph.

Henry Chandonnet is a current student at Tufts University double majoring in English and Political Science with a minor in Economics. He serves as Arts Editor for The Tufts Daily, the preeminent campus publication. Henry’s work may also be seen in Film Cred, Dread Central, and Flip Screen. You can reach out to him at henrychandonnet@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @HenryChandonnet.