Book Review: “Hard Rain” — For Dylan Completists Only

By Daniel Gewertz

It’s a work that shifts gears often, which is not in itself a bad idea for a book about a famed shape-shifter.

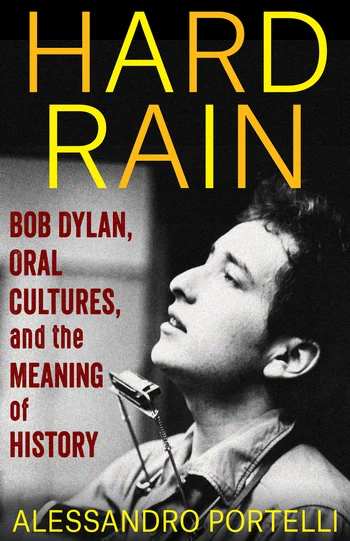

Hard Rain: Bob Dylan, Oral Cultures, and the Meaning of History by Alessandro Portelli. Columbia University Press, 135 pages.

Written by a scholar of the oral tradition in music, Hard Rain is a curious slender, casually constructed book graced with a grandiose title. It comes at Dylan from an unusual angle, but it’s difficult to know to whom the book might appeal, other than Dylan completists. Dense with technical music vocabulary, the 135-page volume is an odd concoction: it drops numerous names and mentions myriad references (many just for padding). Yet, at its best, it supplies a perceptive exploration of both song lyrics and form. Author Alessandro Portelli ends, surprisingly, with an extended storm of Dylanesque anger at the state of the world. It’s a work that shifts gears often, which is not in itself a bad idea for a book about a famed shape-shifter.

It is probable that no volume about Dylan has begun with a more engaging account of the author’s youthful biographical credentials. Here are its first words: “‘A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall’ is the first Bob Dylan song that was ever aired on Italian radio. I know because I was the one who played it.” The Italian professor emeritus of American literature at the University of Rome then tells the tale of his teenage fascination with American folk music. He first heard the commercial side of it — The Kingston Trio and The Limelighters — while a high school exchange student in California in 1960. Four years later, back in Italy, he was given a Dylan album by an acquaintance who’d traveled to America. The Times They Are a-Changin’ wasn’t appreciated in his home: Portelli’s father demanded he “turn off that awful voice.” Luckily, his peers were more accommodating. The brother of a friend allowed folk fan Portelli to play one record of his choosing per week on his Italian national radio show. And so, that “awful voice” made a fortuitous entrance into Italian broadcast history.

After this personable beginning Portelli announces — in query letter style — the academic rigor he intends to demonstrate. But he rarely lives up to his own promises. Despite the author’s field of expertise, the book lacks focus. A good deal of it is devoted to Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall,” and its folk predecessors: “Lord Randal” — the traditional English ballad — as well as an Italian version of the same ancient song called “The Poisoned Man’s Testament.” In the old folk ballad, the story concerns a dying young man who returns to his mother after being poisoned by a lover. Dylan’s song, on the other hand, is extravagantly metaphoric — an ominous, apocalyptic vision of the singer’s travels. Written during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, it reverberated with his audience as a stunningly worded warning of inevitable doom. The melody is precisely the same as “Lord Randal”‘s and the first lines of each verse bear lyrical similarity. A mother and son appear in both, though in Dylan’s masterpiece the vast majority of the lines are uttered in the first person voice of the “the blue-eyed son.” Portelli sees much in common between the simple old folk song and young Dylan’s fiercely expansive reimagining, though the professor’s reasoning is often a stretch. “Hard Rain” is largely a soliloquy. It is, essentially, a different song, the original just a jumping off point.

After telling us how he got hooked on Bob, the author writes of a few other Dylan devotees he’s encountered. Oddly, one early tale — of a Dylan fan growing up in a poor coal mining town in England — meanders along for three straight pages, to no apparent purpose. Was this just ill-chosen padding? Since the author has been a faculty member of the Columbia University Oral History Summer Institute, I assumed the whole book might be filled — or filled out — with taped tales from Dylan fans. But that’s not the case. Very few fan anecdotes ensue, none lengthy. By far the best one concerns Shillong, India. Bizarrely, it is a city totally obsessed with Dylan — the home of The Bob Dylan Café as well as a small annual Dylan festival that occurs on the great man’s birthday, May 24. He’s never played Shillong, or anywhere in India.

The next segment of Portelli’s introductory chapter travels from Shillong to Stockholm, and an intelligent discussion of Dylan’s Nobel Prize for literature in 2017. The most unusual element here is the up-front way Portelli explains his reason for writing this book in the first place. Knowing of Portelli’s early love of Dylan, his Italian publisher “forcibly dragged” him into the book project, motivated to take advantage of the Nobel publicity. Portelli then admits to the reader that he hasn’t closely followed Dylan’s career for several decades, and has never seriously entertained the idea of a scholarly book on the musician before his publisher “insisted” on it. An unusual act of coming clean, indeed. Was it motivated by unease? Occasionally, mid-book, he self-referentially remarks on the writing process — as if it were a long life journey. Though it hardly reads like one given the study’s scant pages. There are also 45 pages of notes. Oddly, for a scholar of oral tradition, he has little interest in being a storyteller in most of the chapters. Only the charming introduction tells tales.

Much of the book wanders through a freewheeling procession of sources. A line from an early Simon & Garfunkel song is referenced. One page bobs about from Bruce Springsteen and New York City mayor Bill DeBlasio to Lord Randal’s mother and the G8 Summit in Genoa. But this particular free-association ends up coalescing well with the assessment that Dylan’s songs “never lose touch with the deep historical forces that shape them, and consign the news of the day to the long duration of archetype or myth, so that the story of the present foreshadows those of the future.”

Portelli’s major perception about Dylan’s appeal doesn’t get much space, but it’s brilliant. Starting as early as 1962, Dylan didn’t foretell a coming apocalypse as much as he proclaimed we’d already reached it: a dark societal road with no escape. Doomsaying became his power. (Does that make “Desolation Row” his No Exit?)

And then, just as one hopes the author will return to Dylan or the ballad form in a substantial way, he’s off on what even he entitles “a digression,” about African migrants from Eritrea, all of whom have brown eyes. He then mentions a few Black singers of the ’60s who changed “Hard Rain”‘s lines about a “blue-eyed son” to a brown-eyed one. Darting farther afield, Portelli claims that one of the images in “Hard Rain” (“I met a white man who walked a black dog”) is about race. Since the song’s lyrics already mention black branches, black forests, and, finally, the phrase “where black is the color, where none is the number,” it is clear to this reader that in this one song, black is synonymous with doom-laden, not an indication of race.

This points up a major flaw in many academic treatises on Dylan. The literature prof presumes that Dylan has shaped every line with a clear intention. Scholars are often fascinated by artists of instinctive genius — those dependent on spells of quasi-magical inspiration. And then these academics diagram the resulting works as if they had been engineered entirely by the left side of the artist’s brain! At one point, Portelli questions some of Dylan’s more cryptic lines in “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” What does the image of “a white ladder covered with water” mean, and might it not be a reference to the biblical Jacob’s Ladder? He would do better to remember that the whole brilliant song was typed out in a single haunted, inspired night. Some of its oddest lines bring chills because their meaning remains so elusive.

Portelli calls this line the most mysterious in “Hard Rain”: “Where the home in the valley meets the damp dirty prison.” He asks if prison and home have been fused somehow, or if a “rural idyll” has been contaminated by incarceration. But he doesn’t supply the obvious answer. This epic song revolves around only two things: the corruption of our society and the inevitability of a future disaster, maybe nuclear, maybe not. When the complacent ’50s first gave way to the ’60s, Dylan was the first ominous voice in youthful pop culture. So, just like almost every other imagistic line in the song, this supposedly inscrutable lyric simply means what so many of the other lines do: the safety of home can easily be decimated by the bomb, or merely by the ongoing desecration of truths and moral values.

When dealing with Dylan’s wildly comic songs of the early ’60s, the interpretive acumen of a writer as humorless as Portelli falls short. “Talkin’ World War III Blues,” despite the post-apocalyptic subject, is a gem of daffy, dazzling comedy. But Portelli sees only disconsolation and pain. (To be fair, his comparison of the song to Bill Haley’s “Thirteen Women,” a post-bomb male sex fantasy, is on target, and his discussion of Vern Partlow’s 1946 “Talking Atomic Blues” is also of interest.)

Traditional folk songs and their long history is Portelli’s field, and he is far surer afoot in that territory. The lengthy history of “Lord Randal” is well handled. But when he tries to link the apocalyptic theme of “Hard Rain” with “Lord Randal”’s subjects of maternal love, mysterious murder, and the legal disposition of wills, he goes haywire. There is no indication, for example, that the hero dies at the end of “Hard Rain”! (The lines: “I’ll stand on the ocean until I start sinkin’/But I’ll know my song well before I start singin’” is not an indication of impending death, but rather, a promise of the troubadour’s true calling.)

As a scholar of the oral tradition, Portelli is naturally fascinated by how much Dylan’s songs owe to older folk and blues. He goes on for a while about “Crash on the Levee” and “High Water” because they closely resemble other folk songs about water disasters. That is Portelli’s prerogative as a historian. But he also implies that these songs are major works because they depend heavily on ancient folk. Yet most would agree that Dylan’s truly great songs — to paraphrase a ’60s phrase — boldly go where no songwriter has gone before.

The next chapter dives into a knowledgeable technical dissection of “Lord Randal” and “Hard Rain.” Portelli has a firm grasp here, though the specialized musical vocabulary is bound to frustrate the lay reader. Some of the pages around the halfway point of the book are cluttered with obscure or specialized words: on one page I found diachrony, orality, systole, diastole, anaphora, and burden. (The latter two concern repeated phrases.) Some of the specialized words were not just obscure but misspelled! Enjambment had an extra “e” stuck in the middle. Synchrony should be spelled with a “y” not an “i”.

But then a lovely thing happened. Right at the point I was giving up on “Hard Rain,” I arrived at a sturdy segment: a lyrical assessment of Dylan’s early songs, highlighting his intensely imaginative use of words and imagery. For a few pages there is fine analytic writing, avoiding an excess of technical terms. Also taking a back seat, thankfully, is Portelli’s frequent tendency to list comparisons without any relevant comment.

He adroitly explains, for example, why a traditional folk song, given its long oral history, has no need for adjectives, how its plot is condensed over the centuries, and that repetition enhances understanding at first hearing and then makes the song more easily memorized and sung. In the murder ballad “Pretty Polly,” for example, there is no reason given for the man killing his female lover. Men kill women, period. But the original version — “The Gossport Tragedy” — specifies an out-of-wedlock pregnancy as the cause of the murder. (One diligent folklorist studied the various versions of the onetime 39-verse ballad, and ascertained the names of both the murderer and victim!) Portelli is also on firm terrain explaining Dylan’s use of anaphora (repetition of words and phrases at the beginning of lines) to build hypnotic power.

But his thinking can be too literal. At one point he even wonders about the term “hard rain,” saying hard rain is merely hail! Often, a dubious comment is quickly followed by a perceptive one. He calls Joan Baez “wrong” for saying (50 years ago!) that she is a more politically active and socially hopeful musician than Dylan, without adequately explaining his objection. But when he then credits Dylan for being uninterested in the Pollyanna-like “Kumbaya” strain of folk music sentimentality, he’s cogent. Reading such an unmoored, free-form academic as Portelli makes me yearn for the solid virtues of journalism. The writing often seems to go in circles, rarely building an argument. He is often content to toss out loosely connected quotes, or snatches of vaguely similar lyrics by others to prove a point. And then there is the occasional bombast. One quote here will suffice: “Alessandro Carrera was absolutely right when he wrote that Bob Dylan’s later albums ‘are perhaps the last modernist poem in American literature.’” To which I say, “Huh?”

The last chapters of Hard Rain include political tirades against America’s perpetual adolescence and the evils of our age. In a way, Portelli inhabits Dylan in his last pages here, tossing together anger and foreboding, often adroitly. He ends — after ignoring much of Dylan’s work post 1964 — with an appendix of several pages devoted to “Murder Most Foul,” his subject’s lengthy, patently bizarre 2020 song that centers on the JFK assassination by way of an increasingly weird slow-motion jumble of famous names, places and catch phrases. The tune might strike one as a brooding, nonsensical invention, a possible goof on a gullible public, Dylan’s parody of his own brand of doom, or a marathon wordplay slowed down to the speed of Thorazine. It may be an unplanned portrait of the artist as an old senile man.

“Murder Most Foul” makes for a sickening contrast to the powerful “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” Dylan has become the man who cannot fail. Hard rain or not, we have fallen a very long way from the flirtation with pop literacy Dylan represented nearly 60 years ago. Portelli, though, seems to include the song to keep up to date, considering the Nobel Prize angle is over five years old. He avoids specific conclusions about the song, though as a final flourish, the professor does make a connection more haphazard than the ones in “Murder Most Foul,” linking Pretty Boy Floyd and George Floyd.

For 30 years, Daniel Gewertz wrote about music, theater and movies for the Boston Herald, among other periodicals. More recently, he’s published personal essays, taught memoir writing, and participated in the local storytelling scene. In the 1970s, at Boston University, he was best known for his Elvis Presley imitation.

Very worthwhile review. A writer myself, I see the appreciation and the work that went into it. Congrats.

Thanks. Always nice to read a good word from a fellow writer!

Dylan wrote Hard Rain months prior to the Cuban Missile Crisis.

This is one of those confusing results of Dylan being a frequent fiction writer (about his own life) early in his career. (He’d tell truly imaginative fibs when he was brand new in NYC.) On the album’s liner notes in ’63, often reprinted, he was quoted by Nat Hentoff as saying he wrote it during the October Missile Crisis. He even went so far as to say he was so scared of the end of the world that he composed it in a single night, with each line being like a separate song… because he wasn’t sure if he had time to write more songs. That’s why the writer of the “Hard Rain” book, and me, and Hentoff, and a lot of other people, have reported it as such. I see from Wikipedia he first performed it a couple of months before the crisis. He recorded it right after the Crisis, in December ’62. Maybe he really re-wrote it in October. Who knows with Dylan, eh?

Very interesting read. My favorite takeaway is that, just like Dylan, his lyrics should not be dissected beyond the imagery.

Good point. It makes me recall one of my interviews with Joan Baez. She had just recorded a song by the then very young Josh Ritter. I told her that Ritter had told me the story and the meaning of the song, which was rather arcane in nature. She said, firmly: “Please don’t tell me. I prefer not to know.” She had learned from all her Dylan songs that the mystery is part of the charm!

The book and reviewers thoughts only seem to further indicate that the only thing we can really figure out about Dylan is that we can’t figure him out

To tell the truth, I always try to read different book reviews because I think that it is important to delve into another point of view and look at the book from a different angle. I can say that I haven’t read such an extensive and detailed review for a long time, but this one was able to attract all my attention with its interesting concept. From my point of view, this book has both its strong and weak sides, but stands out with its own highlight which makes it unique. I really like the manner and style in which this book has been written because it helps you feel everything which the author wanted to convey. I really like how Alessandro Portelly reveals the personality of Bob Dylan, showing all his talent and inscrutability. Of course, this book can cause different ambiguous reactions because it has a lot of cons and it is absolutely not perfect, but the idea has a paramount importance. I think that Alessandro Portelly was able to cover many points of Bob Dylan’s creativity and the oral traditions in a more wide way.