Jazz Album Review: Pianist Cecil Taylor — Lightning in a Piano

By Michael Ullman

“When you play with authority, then that’s what the music is about, like ooooh baby, and sing it.” — Cecil Taylor

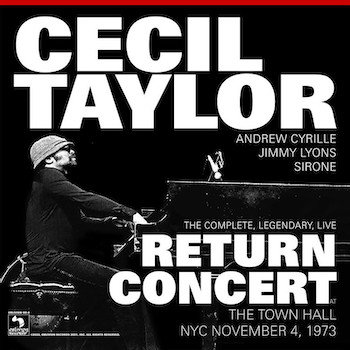

Cecil Taylor: The Complete Legendary, Live Return Concert (Oblivion Records: released exclusively on digital streaming)

Cecil Taylor in Detroit in 1971. Photo: Michael Ullman

In the notes to his 1966 Blue Note album Unit Structures, pianist Cecil Taylor defined jazz as “Naked Fire Gesture.” He added, more obscurely, “Dancing protoplasm Absorbs.” Elsewhere he refers to jazz as “Lightning.” One night in the spring of 1971, in search of that special “lightning,'”I stuffed three wary friends in my Volkswagen bug and drove to Detroit’s Strata Concert Gallery, a cooperatively run club, to hear the Cecil Taylor quartet. It would have been my first time experiencing this elusive giant of the avant-garde. We were met at the door by a disconsolate member of the Contemporary Jazz Quintet who told us that something had gone wrong and that Taylor wasn’t coming to Detroit after all. The disappointment was temporary. The next fall the pianist and his quartet did show up at Detroit’s other alternative jazz spot, the Ibo Cultural Center.

His two long sets were revelatory. As I remember it, Taylor began by playing solo piano, laying out the boundary lines for the music to come. He continued by supplying what seemed to be a series of flashes: every passage seemed to be flying upward. These explosions weren’t grounded in thunderous chords, in the manner of McCoy Tyner, who had also played at the Ibo Center. Taylor was fiery, even desperate-sounding, yet he was light as bells. He liked to play anxious patterns high in the treble. That night he performed with a rapt insistence; his overlapping phrases had the tireless energy of incoming waves. Jimmy Lyons’s saxophone could be equally assertive, yet his phrases seemed content to nestle under the torrent of Taylor’s delicate fury and Andrew Cyrille’s boisterous drumming. I had first encountered Taylor on an early Candid recording, when he played (with Buell Neidlinger and Archie Shepp) “Things Ain’t What They Used to Be.” There he seemed to be playing against the theme, which was carried by others. In Detroit, it was as if the other musicians had been tossed aside.

Next came Taylor’s 1973 solo set in Indent and Akisakila, a Japanese recording (with Lyons and Cyrille) in the same year, and then his own release on Unit Core records, Spring of Two Blue-J’s, an LP with a pretty blue and white cover that was recorded at New York’s Town Hall on November 4, 1973. It turns out that “Spring of Two Blue-J’s” had been the evening’s second set. Oblivion Records has now issued the entire concert, the 88-minute “Autumn/Parade” as well as the 38-minute (and change) “Spring.”

“Autumn/Parade” begins rather peacefully. Taylor plays a short, singable, three-chord theme and holds the chord for a bit before playing several short variations. Lyons enters with his version on the theme, serving up an answering phrase. The saxophonist continues with a variation on that response; he repeats it, as if to make sure it will stick in our heads. Meanwhile, Taylor is dancing all around him. Then, around two minutes into the piece, Taylor plays an ominous version of the three-chord theme in the bass.

This thunder seems to signal a shift in the music, but soon we hear (again) the dancing interplay of the swiftly moving piano and the (relatively) serene alto saxophone, now joined by the slightly underrecorded bass and drums (Sirone and Andrew Cyrille). Lyons drops out temporarily at around four minutes, so the piece essentially becomes a dialogue between piano and drums. After Lyons’s reentry, the piece becomes an agitated — though well-prepared — group improvisation. (Bassist William Parker has commented on this aspect of Taylor’s performances: they would rehearse for a week and then play “free.” Their freedom was made possible by the disciplined work that had preceded it.)

This thunder seems to signal a shift in the music, but soon we hear (again) the dancing interplay of the swiftly moving piano and the (relatively) serene alto saxophone, now joined by the slightly underrecorded bass and drums (Sirone and Andrew Cyrille). Lyons drops out temporarily at around four minutes, so the piece essentially becomes a dialogue between piano and drums. After Lyons’s reentry, the piece becomes an agitated — though well-prepared — group improvisation. (Bassist William Parker has commented on this aspect of Taylor’s performances: they would rehearse for a week and then play “free.” Their freedom was made possible by the disciplined work that had preceded it.)

At times, as in around 10 minutes in, Taylor does his version of laying out: he’ll play more quietly in controlled patterns in the mid-range of the piano. Lyons is let alone to do his thing. The saxophonist plays a stuttering phrase and Taylor stutters in his own way behind him. Elsewhere, even though all four musicians are playing, the spotlight turns on Taylor and the grandiose or fleeting phrases he plays and repeats. New themes enter: for instance, the see-sawing two-chord phrase that Taylor brings in momentarily at around 17 minutes in when he takes over from Lyons. The texture lightens soon after, as Cyrille drops out or down and Taylor converses with bassist Sirone. There are major shifts along the way. I hear what seems to me a transition around 25 minutes in, when everything quiets and Lyons introduces, in a fragmentary way, a new theme. Taylor responds with familiar phrases, but articulates them quietly and slowly until the music builds its way back up. At one point, Lyons seems to be, to my irreverent ears, riffing on the Woody Woodpecker theme. Halfway through “Autumn/Parade” there’s another pause and Taylor seems to reset the stage with his solo playing. The music continues to ebb and flow in ways I find fascinating, if also exhausting.

There is a pattern to the turmoil. Taylor repeatedly plays a short phrase and that will lead to numerous inventive variations. I rather like the transitions. At around 48 minutes, following a particularly explosive few minutes during which Taylor plays particularly knotted phrases, the pianist suddenly stops and softly rumbles around in the bass. Cyrille clicks what sounds like maracas, waiting for Taylor to reset the music. This time it is Lyons who plays a fanfare and repeats it; this gives them enough material to keep the music going until there’s another pause around an hour in. The piece ends when Taylor gently restates a theme by slowing it down — the ritard is a cue to the band.

The previously issued Spring of Two Blue-J’s is the second set. On the LP, it was rationally divided between Taylor’s 16-minute solo (side one) and the quartet set that follows. I am happy to have it digitized, though I am also glad I have the cover of the LP. In his notes to 1966’s Conquistador, Taylor proclaimed, “When you play with authority, then that’s what the music is about, like ooooh baby, and sing it.” Taylor plays with authority on The Complete Legendary, Live Return Concert — and, at times, even songfully.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Andrew Cyrille, Cecil Taylor, Cecil Taylor: The Complete Legendary Live Return Concert