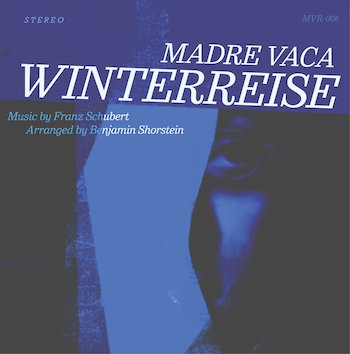

Jazz Album Review: Madre Vaca’s “Winterreise”— Varied Jazz Arrangements Bring Schubert in from the Cold

By Allen Michie

A Mother Cow of jazz iconoclasts takes on German lieder, because why not?

Winterreise, Madre Vaca (Madre Vaca Records)

Schubert schmubert: Who says classical composers need to be treated with deferential reverence? With respect, yes. With an informed approach, yes. With technique, more-or-less yes. But if you’re in a restless and eclectic jazz band, there’s no need to play second fiddle to the original compositions and arrangements.

Schubert schmubert: Who says classical composers need to be treated with deferential reverence? With respect, yes. With an informed approach, yes. With technique, more-or-less yes. But if you’re in a restless and eclectic jazz band, there’s no need to play second fiddle to the original compositions and arrangements.

The jazz collective Madre Vaca (Spanish for “mother cow”) started its own record label and has released 11 records since 2018, two of them under its own name: Nexus (2018) and Nero (2019). Their latest, Winterreise, is a concept album featuring their virtuoso drummer and arranger, Benjamin Shorstein. The disc proffers a jazz take on Franz Schubert’s song cycle “Winterreise,” a setting of 24 short poems by Wilhelm Müller. The loose story line is a man leaves his lover’s house in winter, he gets cold, he momentarily regains some hope, and then he gives up. It’s German.

It’s hard to think of a less obvious or likely source for a jazz album that ranges from trad jazz to Henry Threadgill–style pastiche to New Orleans stomps to Coltrane-inspired outside modal jazz, but that’s what I love about this record. A Mother Cow of jazz iconoclasts takes on German lieder, because why not?

The album opens, paradoxically and appropriately, with the farewell song “Goodnight.” Think Leon Redbone’s band or Postmodern Jukebox covering a Kurt Weill song. There’s a rough-edged New Orleans trad jazz feel with banjo and a cup-muted trumpet, and they expose the cornball melodrama of the original “Gute Nacht” for what it is. If it sometimes sounds like an under-rehearsed group of locals sight-reading from charts, that’s the intent: to exaggerate the contrast with the precious precision of the kinds of classical recordings you’ll hear on Deutsche Grammophon (such as the recording of Winterreise by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Gerald Moore, which I used as my source of comparison here). “The Stormy Morning” similarly takes Schubert on a trip to Bourbon Street, replacing the oppressive march beat of the original with a joyous New Orleans second-line rumba groove.

“Frozen” introduces another style showcasing the impressive versatility of pianist Jonah Pierre: driving, rumbling modal jazz in the vein of McCoy Tyner. “Frozen” and “The Crow” have a more modern swing and tighter ensembles, making Juan Rollan’s powerful tenor sax solos all the more effective. The harmonic core of Schubert’s originals poses no problems for these soloists, though the melodies seem burdensome at times. The melody to “The Crow” is played straight, one note per beat. Shorstein arranges it for different instrument combinations in different keys, but there’s no disguising a melody that simply doesn’t swing. Guitarist Jarrett Carter does what he can, but he doesn’t find much in it to anchor or inspire his solo.

Franz Schubert looking relaxed. Photo: Wiki Commons.

At other times these arrangements are a wonderful gift to some of Schubert’s dreary melodies. “The Hurdy-Gurdy Man” mines the gloomy original song and discovers an exotic, snaking Middle Eastern melody in 6/8 time. “The Weathervane” brings out the waltz rhythm only implied in the original, finding a lively dance hidden in the ups and downs of the melody. “Loneliness” strips away the grim listlessness of Schubert’s original. This version perks it up, blends it a fruity drink (a little umbrella toothpick added), and turns it into a samba. Once heard, you can’t unhear the samba repressed in the melody when you go back to Schubert’s original. Moments like these are what keep this from being just a novelty album.

There are a few oddities (relative to this generally odd record). “Last Hope” is a pastiche of jazz styles, with flashes of stride piano, angular Thelonious Monk–style piano injections, free interplay between piano/guitar/drums, rock rhythms, the tiniest bit of polka, and some Herbie Hancock–style harmonic accompaniment. The closing unison melody sounds flat and dull given the imaginative range of the track. “The Sun Dogs” is a straight reading of the original score, just piano and (uncredited) voice. It’s hardly necessary, especially as the penultimate track, to ease us into the concept of the album. It’s uninspired and works as neither individualized jazz nor polished classical performance. In fact, it lets out much of the creative steam that has been building up.

The packaging is spare, the cover is meh, and there are no liner notes — it would have been interesting to learn more about the arranger’s inspiration and approach. I’m curious to learn how Shorstein landed on Schubert’s “Winterreise” of all things. As it stands, this is a fun and interesting record, worthwhile for Pierre’s diverse piano stylings alone. I hope it will remind jazz arrangers that there’s much more out there to reimagine than the Great American Songbook. Who’s up for Bartok?

Allen Michie works in higher education administration in Austin, Texas, and he has a PhD in English Literature. He has been to Germany in the winter and retains his will to struggle onward.