Book Review: “Fallout” — Memorably Detailing the Defeat of the Hiroshima Cover-Up

By Helen Epstein

I heartily recommend Blume’s excellent Fallout, which ably synthesizes large amounts of archival, historical, and biographical material from three continents.

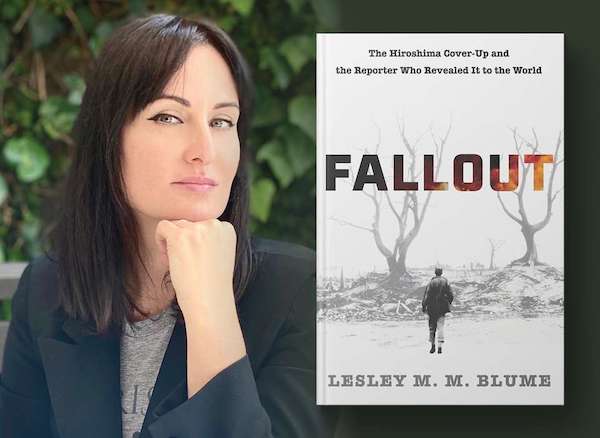

Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-Up and the Reporter Who Revealed it to the World by Lesley M. M. Blume. Simon and Schuster, 276 pp. $27.

Click here to buy

The 75th anniversary of the American atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was overshadowed last month by the turmoil of current American pandemics. And all but lost in the landslide of Trump-related books was Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-Up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World.

In it, author Lesley M. M. Blume examines the extraordinary story behind “one of the deadliest and most consequential government cover-ups of modern times” – the long-term consequences of the American atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki – and the unlikely trio of journalists who brought Hiroshima and the story of six survivors of the atomic bombing to millions of readers, first as a magazine article in the .S and then in book form, across the world. They were John Hersey, then a 31-year old former war correspondent for Time magazine, who had already won a Pulitzer for his novel A Bell for Adano; founding New Yorker editor Harold Ross; and Ross’s deputy editor William Shawn.

In her introduction, Blume describes her book as “the backstory” of how Hersey’s New Yorker article and subsequent book became “one of the most important works of journalism ever created.” On August 6, 1945, about three months after V-E (Victory in Europe) Day, the American Air Force dropped the first nuclear bomb, code-named “Little Boy,” on Hiroshima. Blume writes that “as many as 280,000 people may have died by the end of 1945 from the effects of the bomb, although the exact number will never be known.” The magnitude of the bomb was so incredible at the time that Walter Cronkite, one of the young American war reporters then in Europe, believed that reports of a payload equivalent to more than 20,000 tons of TNT had to be an error and changed the figure to read 20 tons.

That little nugget is a product of Blume’s research, which ably synthesizes large amounts of archival, historical, and biographical material from three continents. This includes background on Hersey’s small group of peers, the war correspondents who wrote with various degrees of candor under US military censorship; the Manhattan Project, in which thousands of Americans worked on a secret project without knowing what exactly they were creating; General Douglas MacArthur, then designated Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers in the Pacific, whose acronym SCAP also referred to the US military administration, which controlled and tried to sanitize the story of what had happened in Hiroshima; Ross and Shawn, “the Hayseed and the Hunch Man,” editors of the then 20-year-old New Yorker magazine, that until the outbreak of war had been read more for its chatty commentary on New York life than for its investigative reporting; and, of course, Hersey himself, the quiet practitioner of what would later become known as the New Journalism.

Many millions of students have read Hiroshima in high school or college but few know much about its pubicity-averse author. Blume does not probe as much as I would have liked into what made Hersey the kind of reporter and writer he was. She seems uninterested in his particulars, including his Christian missionary parents and childhood. In fact, she tells us less than Hersey’s obits do: that he was born in 1914, in Tientsin, China, spent most of his first 10 years there, and spoke Chinese before he spoke English – significant facts for a reporter drawn to write about Asia. When he was 10, the Herseys moved to Westchester County, NY, where he first attended public schools, and later was a scholarship student at the prestigious Hotchkiss School. From there, he went to Yale and then Cambridge before landing a job at Time magazine in 1937.

Blume writes slightly more about Hersey’s relationship with magazine publisher Henry Luce, who identified with him, hired him, and groomed him for the masthead of Time. By 1939, 25-year-old Hersey was working as a foreign correspondent in Asia, where he covered the war in the Pacific while writing his first two novels, Men on Bataan, and Into the Valley, a novel about a skirmish on Guadalcanal. Then – Blume does not explain why and how — he was posted to Moscow, where he opened the Time Bureau. The situation of Western correspondents in Moscow during the war was recently featured in the film Mr. Jones (Arts Fuse review) and it is hard to imagine Hersey being comfortable there. He was also not pleased with how Time edited his stories.

Luce was a rabid anti-Communist and Blume writes that Hersey angrily told his boss that there was as much truthful reporting in Pravda as there was in Time. By July of 1945, Hersey had resigned from the magazine and was back in New York contemplating a novelist’s and freelancer’s life when the atomic bomb was dropped first on Hiroshima and then on Nagasaki. Several of his correspondent friends who covered it wrote him privately about what had happened. Hersey began to think about writing about the aftermath of the bombing for the New Yorker.

Hersey had written his first piece for the New Yorker a year earlier, while still a staffer for Time. It was the story of how naval lieutenant John F. Kennedy, a former boyfriend of Hersey’s wife, had survived a Japanese attack on his PT boat. Hersey did it for Luce’s Life Magazine, which rejected the piece, but permitted Hersey to shop it elsewhere. He sold it to Shawn at the New Yorker, and followed up with what Blume calls a few “military-friendly” war pieces for the editor.

Writer John Hersey. Photo: Wiki Commons.

By the fall of 1945, Shawn and New Yorker editor Ross had become intrigued with the aftermath of the Hiroshima bombing and the subsequent US military attempt to restrict access to journalists. So had Hersey. He decided to spend a month in Asia, beginning in the country of his birth — China — and moving to Japan. No one had yet written a comprehensive story on the fallout in Hiroshima. Hersey, Shawn, and Ross were determined to report on “what happened not to buildings but to human beings.” Rather than try to trick the American occupation forces and sneak Hersey into Hiroshima, the New Yorker presented him as a model war correspondent and war hero who had written admiringly of General MacArthur, now in charge of the occupation of Japan.

Hersey first went to China, where he caught the flu. While recovering, he was given Thornton Wilder’s book The Bridge of San Luis Rey, published in 1927, about the lives of five people killed in Peru when a rope suspension bridge across a canyon broke. That group biography (which centered on a tragedy) gave Hersey the idea for structuring his New Yorker article around the lives of six survivors of the Hiroshima bombing.

Blume traces the intricate and insanely rapid process of Hersey’s research. He was in Hiroshima working for only two weeks. He began by interviewing two missionaries, who introduced him to others who would become characters in the article. He deferred writing what would become a 30,000- word article to New York. Instead he took only notes out of Japan, thereby escaping US occupation censors as well as gaining time. Blume effectively takes us through Hersey’s choice of interviewees, the interviews themselves, the writing and editing process with Ross and Shawn. They published what became the 30,000-word article on Aug. 31, 1946. Albert Einstein ordered a thousand copies for distribution and it was reprinted and serialized as well as published as a book that sold millions of copies internationally and helped create the nascent postwar peace and anti-nuclear movements.

Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-Up and the Reporter Who Revealed it to the World breathes new life into an old book, resuscitates an extraordinary story, and tells it well at a time when journalists like Hersey are finding it more and more difficult to publish vital stories, when journalists and their craft have been devalued by propagandists and publishers who’ve cut back on their support (money, copy-editors, fact-checkers) for investigative journalism.

It’s become disappointingly infrequent to read a substantial, well-written, and well-edited nonfiction book. So, while I would have liked to have read more about Hersey himself, about how his childhood informed his work, and why this reticent man who preferred writing fiction to reporting became the journalist who reported on the long-term consequences of the bombing of Hiroshima, I heartily recommend Blume’s excellent Fallout.

Helen Epstein is the author of 10 books of non-fiction and most recently edited her mother’s war memoir Franci’s War.

Just a note that, besides this book (I trust Helen), those interested in the cover-up of Hiroshima should turn to Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Michell’s indispensable 1995 Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial. The study takes a scathing, meticulously factual look at the obfuscation and repression that has driven the dominance of the ‘official story,” which rationalizes the dropping of the bombs. It also chronicles the years of determined sanitation, culminating in the debacle of the Smithsonian Institution’s botched (and censored) attempt to deal with the human effects of the bombing in its exhibit on the 50th anniversary of Hiroshima. Nothing had been scheduled at the Smithsonian this year to commemorate the anniversary! (In March, the LA Museum had put on the exhibit Under a Mushroom Cloud: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Atomic Bomb. The show is a collaboration between the Japanese American National Museum and Hiroshima Peace Museum in Japan. The JAMN is “planning to extend Under a Mushroom Cloud when the museum reopens to the public. It will provide a new closing date once it has been determined.”)

Significantly, given where we are today, Hiroshima in America backs up its first sentence: “You cannot understand the 20th century without Hiroshima.” Why? “”Hiroshima signified the pointless apocalypse — the sudden realization that we could extinguish ourselves as a species, with our own technology, by our own hand, and to no purpose.”

The book’s look at the resonance of that vision — culturally, psychologically, and morally — makes it particularly relevant now. Our continued acceptance of “Hiroshima distortions was bound to have its effects on the America psyche and American history … the cumulative influence of Hiroshima turns out to be much greater than most Americans suspect. Indeed, one may speak of the bomb’s contamination not only of Japanese victims and survivors, but of the American mind as well. But that very contamination — the aberrations in American life induced by Hiroshima — if confronted, can become a source of renewal.” Hersey’s book on Hiroshima was the first substantial examination — but Lifton’s monumental 1969 study Death in Life remains the best exploration of the bomb and its catastrophic effect on humanity.

The connections between Hiroshima and the Climate Crisis are obvious — our love/hate of the apocalyptic, our commitment to denial rather than confrontation — and these are examined by Lifton in another invaluable book, 2017’s The Climate Swerve: Reflections on Mind, Hope, and Survival.

I found Helen’s review thoughtful and compelling. I read Ms. Blume’s book, noting that, conspicuous by its absence, was any mention of Hersey’s relationship to James Agee, who later went on to become a literary giant.

Agee and Hersey were colleagues at Time Magazine. Many years later, Hersey chose him as the subject of “A Critic at Large” for The New Yorker, mentioning their friendship.

Agee is to be commended for writing an unsigned editorial piece for Time that would have deeply moved Hersey, and, I believe, inspired him to pursue his groundbreaking reporting in Japan:

“The rational mind had won the most Promethean of its conquests over nature,” Agee wrote, “and had put into the hands of common man the fire and force of the sun itself. Was man equal to the challenge? In an instant, without warning, the present had become the unthinkable future. Was there hope in that future, and if so, where did hope lie?”

But Blume left this important connection out of her book, a glaring error.

Excellent point, Bob. Agee’s Let Us Praise Famous Men (1941) pioneered Hersey’s journalist approach in Hiroshima. Perhaps Blume thought it made Hersey look more inventive/heroic by suggested that he and his book came out of nowhere. One note: a recently discovered Agee text, Cotton Tenants: Three Families, written in 1936 with photographs by Walker Evans, was published by Melville House in 2014. It is a marvelous text with particular relevance given the coming age of global hunger.

A salient passage:

Would Hersey be capable of writing this? I think not …