Book Review: Amina Cain’s “Indelicacy” — Brilliant, But Icy, Minimalism

By Katharine Coldiron

Amina Cain’s style is unusual, and it may tow readers so rapidly through this brief novel they won’t look back.

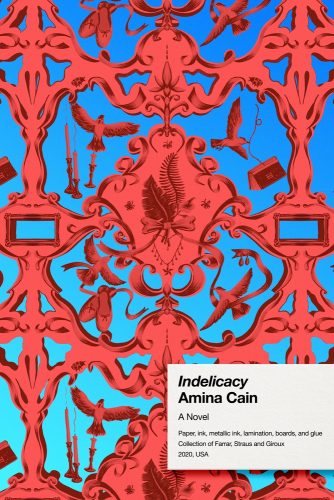

Indelicacy by Amina Cain. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 176 pp, $25.

“Writing is endless, what it allows you to consider,” explains Vitória, the first-person narrator of Amina Cain’s new novel. The book proves this point neatly. Indelicacy fits an extensive sheaf of ideas into its minimalist prose and story, like a deep-focus shot in a masterful film. However, books worthy of study are not always the most enjoyable ones. Cain’s style is not for everyone, and those who read for pleasure might find Indelicacy a bit too prickly to develop affection for it.

Admiration, however, comes easily. Vitória’s story is deceptively simple: she begins the novel as a maid in a museum, trying to write and unable to find time for it; she marries a rich man, who allows her to stop work; she loses interest in the marriage and develops a combative relationship with her maid; she forces her husband to divorce her, and winds up “free,” to write and to live without having to work as a maid or a wife. Running through this story like bright threads are big ideas: how creativity is lost to capitalism and duty, how class divides women who ought to be on the same side, how necessary solitude is to the act of writing.

Instead of embellishing this story with subplots or even very many scenes, Cain offers mere crumbs of information and atmosphere, inviting the reader to think about the themes of the novel rather than staging its conflicts with much specificity. Her endeavor demonstrates how little architecture a novel actually needs to stand up. Cain has shaved it down to a character with a desire and a series of events that either ease or hamper her trajectory toward that desire. Her economy approaches Lydia Davis’s, or that of a poet whose sole pen is running out of ink.

Moreover, Cain’s sentences are sharp, forthright, unearthly. “In a department store I saw earrings that looked like drops of blood and I wanted to wear them.” “Only rarely did I see her in repose, sitting in the garden with a newspaper in her lap, eating food sent to her by her family.” “After my bath, I sat in front of my mirror and thought about death.” There’s something unapologetic about her prose, bordering on hostile, that makes it rare and fascinating. She has placed each word with such care that readers may worry they aren’t adequately appreciating the effort it took to write a novel with such poetic diligence.

Yet, economy like this is a flame burning brightly with no warmth. Vitória’s desire to write, and her struggle to find circumstances suitable for writing, calls on the struggle of women writers back to Woolf and well beyond. But for Cain it’s an intellectual puzzle, a labor devoid of emotional richness, a sample inside an airless glass bell instead of a warm, breathing thing. This quality makes Indelicacy a praiseworthy novel, but one not especially fun to read. Such blunt, intense sentences—and a lack of definition on the time period or location of the novel—may leave readers feeling adrift, unable to plant themselves in a tactile world and root around in it.

For others, this lack of emotional engagement will not matter. Cain’s style is unusual, and it may tow readers so rapidly through this brief novel they won’t look back. Further, she (along with other writers who, like Cain, previously published with the small press Dorothy) has nudged minimalism further away from the grasp of last century’s all-white, all-male concerns and made it dance to a feminist tune. Late in the book, Vitória attends a reading and conversation between two male authors: “I wanted to lock them in the room after the reading was over and make them listen to each other forever.” In speaking of her husband, she tells a sly truth: “If I were another kind of woman, maybe I wouldn’t have let him out of my sight.… I was naturally out of his sight, as women usually are with their husbands. It gave me great freedom.”

Restlessly, Vitória turns to visual art for answers and solace, but doesn’t exactly find either. Her writing, too, provides inconsistent comfort: “Sometimes I am immersed in my writing, ecstatic; sometimes I am only able to write one paragraph. On certain days I hate that paragraph.” Visual art plays as important a part in this novel as writing, but its significance remains in the subtext. “In every painting, someone or something emerges,” Vitória writes.

What is it that emerges from paintings? From this novel? What emerges from Vitória’s writing, or from Cain’s? Even in the closing pages, it remains unclear. Impressions. Ideas. A strong respect for a brilliant and idiosyncratic writer. But a story that will stick with you for years, or give you a thrill, or lighten your load? Nope. That’s not what Amina Cain is here to do.

Katharine Coldiron‘s work has appeared in Ms., the Guardian, the Rumpus, and elsewhere. She lives in California and blogs at the Fictator.