Visual Arts Review: Go Worlds Away at SoWa Boston

Both galleries have successfully paired photographers who work in parallel idioms and who, through simple visual details, deliver a vivid sense of place tinged with memory and nostalgia.

Works by Wei Bi and Mehran Mohajer at Ars Libri Gallery, 500 Harrison Avenue, Boston, MA, through May 25.

Works by Judy Brown and Meg Birnbaum at the Griffin Museum @ SoWa, 530 Harrison Avenue, Boston, MA, through June 11.

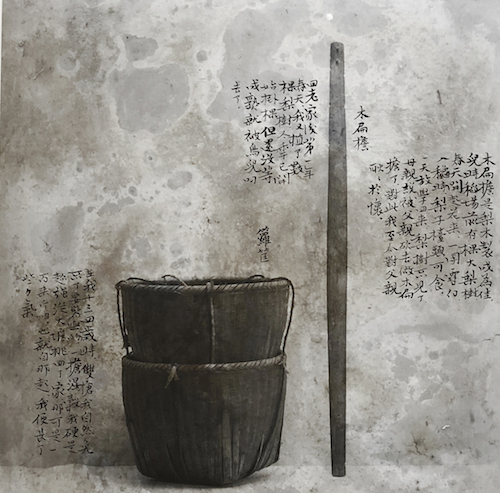

Wei Bi, “Shoulder Pole for Carrying Large Bamboo Baskets,” 2007-2013 , from the Mengxi II series. Courtesy of See+ Gallery, Beijing.

By Kathleen Stone

These two photography shows in the South End transport you far from the gritty hipsterism of SoWa Boston. The Ars Libri Gallery takes you to China and Iran, while the Griffin Museum deposits you in rural Massachusetts, closer in miles but still worlds away from Harrison Avenue. Both galleries have successfully paired photographers who work in parallel idioms and who, through simple visual details, deliver a vivid sense of place tinged with memory and nostalgia.

Wei Bi’s photos, at Ars Libri, draw on his childhood in rural China. Each picture shows a single ordinary object from his village in Hunan Province, often from his father’s house. A drying rake, a withered sweet potato, a pile of roof tiles, a double happiness jar, a pair of felt skippers: quotidian items in China’s rural life. He uses a similar compositional arrangement throughout — a single object in matte black is placed against a mottled gray background. The austerity gives off a totemic quality. The artist adds hand-lettered calligraphy to the images; the delicate tracing of black ink provides a counterbalance to the blackness of the object while the writing also personalizes the picture. Even if you are unable to read the Chinese characters, you sense he is writing about people close to him who once wore the slippers, or dug the potato from the ground, or acquired the jar on their wedding day. The nostalgia is palpable, even from the other side of the globe.

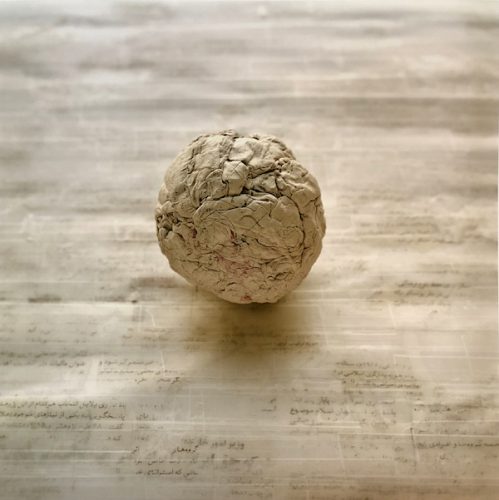

Ars Libri is also exhibiting the photos of Mehran Mohajer. They, too, picture a single object with text, but they take us to cosmopolitan Teheran instead of rural China. Mohajer studied linguistics and photography at the University of Tehran and now, in addition to being a photographer, he writes and translates poetry. His objects are as descriptive of his world, one of urbane and intellectual pleasures, as Wei Bi’s are of his. Balled-up newsprint suggests reading in a tea house, a slab of white marble alludes to intricate carvings, a tintype case conjures up vintage photographs, and a dried slice of fruit evokes refined Persian cuisine. His palette is soft, emphasizing ivory, brown, rust, and glossy black with flecks of red and green.

Mohajer also uses text in his images, but his approach differs from that of Wei Bi’s. Farsi script — probably pages of poetry he composed or translated — make up the backgrounds of his photos. Sometimes the words are obscured by water spills or shadow, but that only heightens our appreciation of the way these objects signify an ancient culture. Both Mohajer and Bi are artists who invest single objects with an emotional resonance so great that we feel their pull, both personal and cultural, even while standing in a gallery in Boston.

Mehran Mohajer, Untitled. From the Things & No-things series, 2011. Courtesy of the artist.

Just a few steps down Harrison Avenue is the Griffin Museum’s SoWa outpost, which is presenting photographs of animals found on Massachusetts farmlands. Photographer Judy Brown examines these critters close up, and her attention to detail is aborbing. These photos are delicately observed portraits: the long eye lashes of a lamb, the wirey hair of a pig, the ruffled forelock of a cow. In her artist’s statement for the show, Brown discusses her determination to capture each animal’s personality, to evoke its humanlike qualities. To some viewers, this anthropomorphism may come off as a little forced. But it is inescapable that looking straight into an animal’s eyes and noticing, for instance, how one forelock differs from another, makes us notice animals as individuals, rather than as members of a disposable herd.

“Baby,” Judy Brown, Courtesy of the Griffin Museum.

The Griffin is also displaying the work of Meg Birnbaum. The backstory to her photos is, alas, sadly familiar. A couple who make their life on a farm lose its land. Sadness and dread threaten to overcome the family’s love of the beauty of their fields. In one photo, the man holds his young son on his shoulders. The former’s eyes are closed, forestalling the inevitable tears — but the boy’s are open, apprehensive. In another picture, the couple makes its way home from the fields. We see them from behind, at a distance. They hold hands, and we sense, and hope, they will go forward together, even after the farm is gone.

Beyond the poignancy of the situation, Birnbaum brings a keen sense of composition to her photos. Even a sight as simple as two greenhouses sitting side by side create an echo of form. The curly tail of a black pig is as tactile as the tree roots among which he pokes. In one particularly striking picture, a farm hand grasps the bodies of three Rhode Island Red hens. Improbably, she wears a string of pearls around her neck; the pearls set up a visual motif of rounded forms, from the worker’s open neckline to the hens’ bodies to the cuffs of the rubber gloves that poke out of her jeans pocket. The image was so impressive I assumed it had been posed. But Birnbaum assured me, when I met her at the opening, that the shot was spontaneous — this farm hand really did wear pearls.

The photos in both galleries remind us that traditional ways of life — close to home as well as far away — continue to disappear. We should be grateful for artists and writers all over the world who are witnesses, and help us remember the value of what is passing.

Kathleen Stone lives in Boston and writes critical reviews for The Arts Fuse. She co-hosts a literary salon known as Booklab and is at work on several long projects. She holds graduate degrees from the Bennington Writing Seminars and Boston University School of Law, and her website can be found here.

Tagged: Ars Libri gallery, Judy Brown, Kathleen White, Meg Birnbaum, Mehran Mohajer, photographs