Poetry Review: Henri Cole’s “Touch” — Love Thy Neighbor, Like Thyself

Is it true that if I love my neighbor I can, or will, like myself? This question cuts to the heart of the poems in Heni Cole’s volume Touch, and the answer is yes.

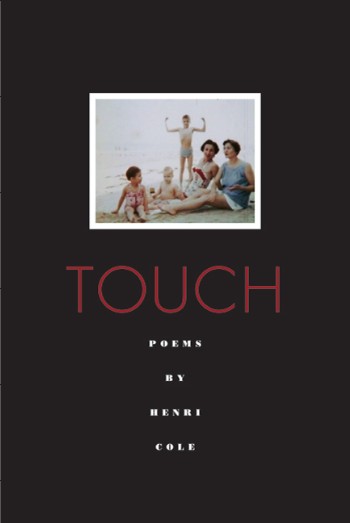

Touch by Henri Cole. Farrar Straus Giroux, 80 pages, $23.

By Daniel Bosch

Just before the volta in Henri Cole’s sonnet “Bats,” the first poem of the third and final section of Touch, an intimate, new installment of Cole’s biography-in-verse, there is a poem-within-the-poem, legible in a slow, close reading of lines seven and eight:

they hit one another’s furred wings—Love thy neighbor

like thyself—and then soar off again to drink . . .

“They” in line seven refers to bats under the empathic surveillance of the Cole’s speaker. One way to paraphrase the line is to see these barely visible, blind mammals touching their exceedingly long fingers—skin stretched over and between them—as they fly past each other, as if “knocking the rock” or fist-bumping by echolocation. Cole’s line supports such a reading by changing registers so drastically at the em dash: we’re reading about bats, and then we’re suddenly enjoined by the speaker to follow Jesus’s “Golden Rule”? Yet it’s pleasant enough to imagine voracious bats in sightless flight achieving the kind of Christianity we humans find so difficult.

Cole’s enjambment of line seven into line eight at “neighbor” emphasizes the integrity of the line, something always worth paying attention to in a poem by Cole. As an independent unit, line seven stresses the violence with which these bodies touch—“they hit one another . . .”(italics mine), but violence ends in a compassion we associate with humans rather than rodents: “Love thy neighbor.” When the rock explodes, in line eight, and the bats “soar off again to drink,” the encounter is anthropomorphized even more strongly; in Cole’s speaker’s account, even brief contact with the other, a mere touch, is fraught and sends both parties off in search of a drink, in this poem’s case, a bleach cocktail.

But these lines’ deftest touch is in how Cole translates Jesus’s “Golden Rule” as he breaks it across his enjambment. Every version of the New Testament I’ve read follows the King James Bible and translates the Golden Rule “Love thy neighbor as thyself” (my italics). Cole’s queering of the biblical text is the more surprising because I am prepared, by the moment’s hesitation at the line break, to receive, in the beginning of line eight, the unrevised, standard version. Yet “Love Thy Neighbor” in Cole’s newer testament leads instead to what sounds like a command, at the beginning of line eight, to “like thyself” (emphasis mine). The bats are just doing their batty thing, but Cole’s speaker joins with them as they supercharge the gloaming atmosphere. Is it true that if I love my neighbor I can, or will, like myself? This question cuts to the heart of Touch, and Cole’s answer is yes. The experience of how he supports such an affirmation, in spite of the risks of being touched, is one of the pleasures of this heart-rending book. But the genius of Henri Cole’s lines is in how casual they seem, even as he loads them with meaning.

Touch is divided into three Roman numeral-divided sections. Arts Fuse readers may recall that I have made fun of the tri-partite mode as a default poetry book structure (see my review of Zagajewski’s Unseen Hand), yet here Cole’s three sections neither posit nor imply a fictional Hegelian triad. Each section is 14 poems long, and the number resonates with Cole’s choice of form for most of the poems in Touch: 43 of its 52 poems are sonnets; one is a double-sonnet. Each section is introduced by an epigraph from one of Cole’s familiars, a spirit who presides, implicitly or explicitly, over that section: Cole’s Mother (I), Elizabeth Bishop (II), and W. H. Auden (III).

Open Touch to its first page and you meet Mother Cole’s admonition: Don’t be an open book. Immediately we realize that this son does not obey his Mother—we hold his book open in our hands, and the poet is there to be read on its pages. Yet Cole’s choice of the sonnet—even if they don’t rhyme, his twist and turn within tight bounds—suggests how Cole has negotiated, in Touch, both the demands of Mother and the demands of art without compromising either: I must be an open book, so I’ll write Touch in closed form; or, I must open up my poems, make my book and myself more vulnerable now that she is gone, so in them I’ll swerve at the volta—sometimes toward face-saving indirection. Mother Cole’s final days, and the first days following her death, touch all of the poems in the first section. Here is “Sunflower”:

When Mother and I first had the do-not-

resuscitate conversation, she lifted her head,

like a drooped sunflower, and said,

“Those dying always want to stay.”

Months later, on the kitchen table,

Mars red gladiolus sang Ode to Joy,

and we listened. House flies swooped and veered

around us, like the Holy Spirit. “Nature

is always expressing something human,”

Mother commented, her mouth twisting,

as I plucked whiskers from around it.

“Yes, no, please.” Tenderness was not yet dust.

Mother sat up, rubbed her eyes drowsily, her breaths

like breakers, the living man the beach.

Do you hear the “son” in “sunflower”? Now instead of bats it’s house flies that trace invisible halo arcs in the air. And now it’s mother and son; he’s plucking masculinizing whiskers from around her mouth, and she is prone in an estranged, reversed pietà. Note the precision of the flower simile: her head is raised and it droops. Is the embarrassing ambition of a healthy sunflower, the heliotropism that eventually breaks its neck, an evolutionary advantage even if it makes every sunflower, at the end, less beautiful? Look at all those seeds scattered on the ground! A memory of birds closes the first section, as if Cole wanted to complete the set of flying things:

Remember how they sang with their beaks closed

when we set them free each night,

listening and watching

as they circled overhead

in the bright lights that imitated daybreak?

Remember the notes that resembled bubbling water?

What a fine performance they gave!

Though they didn’t know where they were going,

they made the prettiest song of all.

Mother Cole’s comment, “Nature is always expressing something human,” which could have been the epigraph for the whole book, sounds almost like an order to her son: Pursue the pathetic fallacy! Thankfully, Cole resists, the way the beach resists the sea.

Two lines from Elizabeth Bishop’s poem “Sandpiper” bless the second section of Touch: “His beak is focused; he is preoccupied, // looking for something, something, something,” and we feel the mimesis in those “somethings,” each one stabled into wet sand. (Compare it to Frost’s indelible image of how “the wetter ground like glass // reflects a standing gull,” where “gull” is both the seabird and the foolish human who can see, a the shoreline, “Neither Out Far Nor In Deep.” Bishop’s bird is at least after a bellyful.) So the middle passage of 14 poems is the most searching of the three, in the sense that Cole’s speaker, unmoored from the death of his Mother, wanders, hungrily and persistently but with a great deal more intelligence than a sandpiper. Animals and insects abound—birds, of course, and a spider and a stuffed fawn, a brief mention of a donkey, and a make-believe elephant with a phantasm at the end of its name. There is a dream poem and a poem about an execution (you make the connection) and two ecumenical, ekphrastic poems, one about a Piero della Francesca, one about a newspaper photo of U.S. soldiers sleeping. The emblematic sonnet of section two is “Pig”:

Poor patient pig—trying to keep his balance,

that’s all, upright on a flatbed ahead of me,

somewhere between Pennsylvania and Ohio,

enjoying the wind, maybe, against the tufts of hair

on the tops of his ears, like a Stoic at the foot

of the gallows, or, with my eyes heavy and glazed

from caffeine and driving, like a soul disembarking,

its flesh probably bacon now tipping into split

pea soup, or, more painful to me, like a man

in his middle years struggling to remain

vital and honest while we’re all just floating

around accidental-like on a breeze.

What funny thoughts slide into the head

alone on the interstate with no place to be.

It is a funny picture and a moving analogy, the identification of the poet with a load of pork “enjoying the wind . . .” its bristles like strings of an Aeolian harp, both man and pig “like (souls) disembarking . . . // . . . accidental-like on a breeze.” Being a teacher myself, and knowing that Henri Cole teaches at Ohio State University, makes me wonder if the speaker who observes this pig is driving toward his day job in academia,

. . . a man

in his middle years struggling to remain

vital and honest . . .

Poet Henri Cole — the genius of his lines is in how casual they seem, even as he loads them with meaning.

No one who reads the third section of Touch will doubt that Cole has mastered this struggle or that a soft-spoken, daring art is the means by which he has achieved such mastery. Its epigraph is from “In Memory of Sigmund Freud,” one of the last great, public poems composed by Auden on the cusp of his arrival in the new world. Cole snatches from it a frame for an elliptical love story (not to say a family romance), the fragment, “To be free // is often to be lonely.” This set of 14 poems records, in its way, what it was like for the speaker to be intensely, sexually, lovingly involved with an abusive drug addict—a record as Robert Lowell had it when he said that “a poem is an event, not the record of an event.”

The section begins, as I did, here, with “Bats,” a poem that records, in its observation of what comes naturally, the proximity of agape and violence. Throw sex into the mix and add three swallows of that older testament shame that keeps a man from saying “I am gay” and a glug of that newer testament pride at being able to write in a poem (and in one’s life) “I am gay,” and the results are inflammable. “Bats” closes with the speaker no longer able to watch, or listen, to his fellow Christians: “I can hardly stand it and put my face in my hands, // as they dive to-and-fro through all their happiness.”

Here as elsewhere in Touch, Cole’s imagination draws elements from the deep and the near past together with immediate, palpable, and searing present events, as in “Quilt.” The opening image is of the domestic object, perhaps made by a grandmother or Mother Cole, comfortingly gathered around an ill Henri. But the sonnet form allows no time for any recovery, and in a brilliant jump-cut to the present, Cole juxtaposes this picture of his feverish child-self with his adult arrival “with a new lover” at a family gathering.

Little muslin sacks from chewing tobacco,

home-dyed in pink and yellow, pieced as a zigzag—

a lively recycling of materials seen often in the South—

with sturdy stitches and a two-color scheme,

like a temperature chart pulled up around me.

What temperature is Henri, the black sheep,

arriving unexpectedly with a new lover—alcoholic

and impetuous—jolting the rest of the family

into spasms of pity, resentment, and half admiring

amazement at his sheer nerve? I’m sorry I broke

the Ming Dynasty jar and set Poppop’s beard on fire.

I could actually be normal if the imagination

(unstable, disquieting, fragile) is the Father penetrating

the Mother and this is my Child-poem.

In the self-reflectiveness of the question “What temperature is Henri, the black sheep,” Cole echoes the posturing protagonist of John Berryman’s Dream Songs. But where “Huffy Henry” poured on the bravado and poured down the sauce, “Henri, the black sheep” is soberer and in possession of a touching empathy for his judges. To be with his family is to re-enter a cartoon world, where the child is always letting everybody down by breaking the priceless porcelain or burning somebody’s nest. The poem is “a lively recycling of materials” in the best sense, the “Child-poem” of a man who will not, perhaps, supervise anyone else’s childhood but who has recovered from some of the familial illnesses that plagued his own and who makes lines and sentences that live will outlive him.

The New Yorker has recommended Touch as one its “Reviewer’s Favorites for 2011” with the terrifically concise and accurate phrase, “Poems of voluptuous candor.” I couldn’t, and haven’t, said it better. The closer one gets to Henri Cole’s Touch, the more generous both poems and author seem.

Always a pleasure to read Daniel Bosch here.