Theater Review: Notes on Shakespeare as a Bare Bard

Two recent productions of Shakespeare, one a heralded British staging heading to New York in April, the other an Actors’ Shakespeare Project presentation in Davis Square, provide examples of the strengths and weaknesses of tackling the Bard without frills.

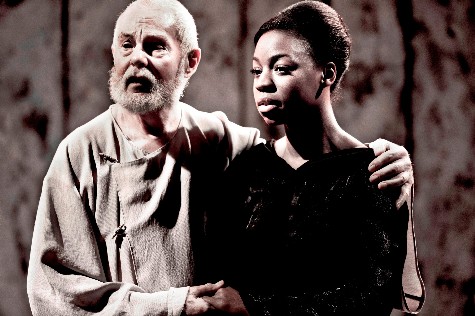

Derek Jacobi (King Lear) and Pippa Bennett-Warner (Cordelia) in the Donmar Warehouse production of KING LEAR. Photo: John Persson

King Lear by William Shakespeare. Directed by Michael Grandage. Presented by BAM and the Donmar Warehouse at the BAM Harvery Theatre, Brooklyn, N.Y., April 28 through June 5. Also, there are NT Live screenings of King Lear throughout New England in February and March. Check the NT Live site for venues and showing times. There is a Coolidge Corner Theater showing on February 26 at 10:30 a.m.

Cymbeline by William Shakespeare. Directed by Doug Lockwood. Staged by the Actors’ Shakespeare Project at the Storefront on Elm at Davis Square, Somerville, MA, through February 20.

By Bill Marx

Earlier this month I caught the NT Live screening (at the Coolidge Corner Theatre) of a much ballyhooed production of King Lear staged at London’s Donmar Warehouse in London, featuring Derek Jacobi as the unfortunate king. For once the tidal wave of critical adoration is well earned—this minimalist but mighty Lear, performed on a bare stage, tackles the epic script with an impressive muscularity and drive, seeing it as a passionate study in the deconstruction of identity, the deluded ego buffeted by arrogance and age.

Those who have the time and money to catch the production at BAM in New York (April 28 through June 5) should take advantage of the opportunity, though with the caveat that the intimacy of the small Donmar Warehouse space, suggested by the juicy close-ups in the NT Live Screening, will cut down on some of its merits. My tip is to bring your opera glasses to catch the illuminating details in the first-rate performances. (Also, there are NT Live screenings of King Lear throughout New England in February and March. Check the NT Live site for venues and showing times. There is a Coolidge Corner Theater showing on February 26 at 10:30 a.m.)

For me, Jacobi has rarely been better; this is a full-throttle performance from an actor who sometimes seemed to pull back. Jacobi has always had an air of prissiness (see his turn as a cleric in the film The King’s Speech), which made his Richard II as a fallen aesthete more memorable than his somewhat hollow Prospero, who came off as more grumpy than commanding.

In Lear Donmar Warehouse director Michael Grandage takes brilliant advantage of Jacobi’s fussiness in the first scene, presenting Lear as a vain monarch, a bit of a wise-cracking bully, who discovers, and is then destroyed by, the knowledge that his once unquestioned power to intimidate rests on the bloody whirligig of time. Blustering, his face turning beet red in childish anger, Jacobi’s Lear descends into madness (or senility) via an internal shredding of egotistic illusion, a humbling of self-satisfaction in the face of crushing reality.

Pippa Bennett-Warner suggests in her nimble Cordelia that the youngest daughter is a narcissistic chip off the spoiled old block—she thinks innocence alone protects, much like Lear, and that is an unforgivable sin in the Bard.

Sisters Sinister: Justine Michell (Regan) and Gina McKee (Goneril) in KING LEAR. Photo: John Persson

Grandage cuts the script in ways that keep the action driving ahead without losing the poetry and the complexity; the set, a box made of white boards, puts the emphasis on the acting, and it is generally at a very high level. Standouts include Gina McKee’s gloriously smoky-voiced virago of a Goneril, who has a terrific scene holding Albany’s crotch, squeezing tighter (to the beat of iambic pentameter?) while telling him she can treat her dad however she wants. (My late critic friend Arthur Friedman would have loved it.) The weakest performance comes from Alec Newman as Edmund, though this may be Grandage’s stratagem: to play down the energy of charismatic villainy in order to emphasize the pathos of Lear’s breakdown. Still, caught between McKee’s Goneril and the vibrant viper of Justine Mitchell’s Regan, Newman looks like a cub mugged by tigresses.

Ron Cook’s Fool is sardonically amusing but somewhat conventional; what is most interesting (and new) here is how Jacobi’s Lear treats the Fool with a tenderly tough competitiveness, as if the monarch is even picky about the jokes he hears. Gwilym Lee’s Edgar falls a bit short as an avenger, but the long-suffering character’s treatment of his blinded father, Gloucester, and Lear is evoked with a rare delicacy—this is not only a play about growing old but about how to treat the elderly with dignity.

Finally, this production contains one of the best dramatizations of the storm scene that I have ever seen. Grandage makes amazing use of beams of light flickering though the empty set’s floorboards and walls, but, even better, the chiaroscuro evokes an internal rather than an external melt-down. There’s no overwhelming bouts of thunder and lightening, no screaming and careening around the stage. The ”Blow, winds, crack your cheeks! rage! blow!” and “Rumble thy bellyful! Spit, fire! spout, rain!” speeches are treated as fleeting thoughts in Lear’s crumbling mind—Jacobi whispers the words. Chilling and wonderful stuff . . . the first time I have ever been able to make out every line during the melee, because Grandage doesn’t feel the need to whip up chaos—instead, he focuses on the efforts of the characters to maintain sense amid senselessness, which is what Shakespeare’s poetry struggles to do as well.

Another attempt to do a stripped-down version of the Bard, the Actors’ Shakespeare Project’s (ASP’s) staging of Cymbeline , is more problematic, though not because of the choice of the play, a late (1610) script that many critics consider to be, in the words of the Washington Post‘s critic Peter Marks, an “iffy achievement for Shakespeare, what with subplots recycled from weightier efforts and characters lacking in lightning-bolt impact.”

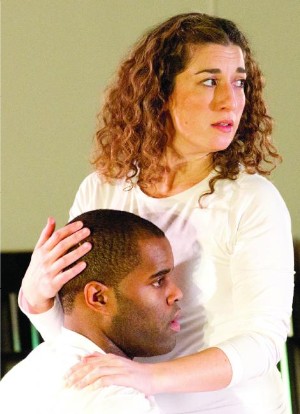

Love Endangered: Brooke Hardman (Imogen) and De’Lon Grant (Posthumus) in the ASP production of CYMBELINE.

The “greatest hits” aspect of the script doesn’t mean that the Bard turned in desperation to recycling: in fact, it could be argued that this miraculous play, rather than The Tempest, represents the dramatist’s real farewell to the stage. Yes, the latter dramatizes a wizard giving up the mechanics of magic, but Cymbeline is the product of a veteran playwright pulling out all the stops and then some, generating magnificent poetry, eye-popping, rabbit-out-of-a-hat stage tricks, and astonishing psychological insights. (Incredibly, a clueless Boston Herald “review” of the production considers the play without a single reference to its poetry, referring to the evening as a “wordy whirlwind.” Guess what—all of Shakespeare’s plays are hurricanes of syllables.)

Thus the ASP should be congratulated for producing the play—the only professional staging that I can remember in the Boston area is a solid 1990 production at the Huntington Theater Company. No chance to hear the gorgeous lament “Fear no more the heat o’ th’ sun,/ Nor the furious winter’s rages” or the affecting proclamation of love—”Hang there like fruit, my soul, / Till the tree die”—should be passed up.

The problem is that in an effort to clean up the ultra-complicated action, which jumps from ancient Britain and Rome to Wales, director Doug Lockwood has cut huge hunks of the script in order to focus on the bizarre trials and tribulations of Imogen, meritorious daughter of King Cymbeline, and the fate of her marriage to the poor, gallant, but thick-headed Posthumus. The approach is not new, but it ends up reducing the fascinatingly thorny script (with its religious, historical, and political conflicts) into a lyric romance, a pure and simple fairy tale with a few kinky, violent bumps complicating the road to the final embrace.

This is Cymbeline lite, an air-brush job that’s reinforced by having a cast of seven (dressed in white) playing a number of roles, the action taking place on a floor covered with rugs. Sometimes the idea is dramatically effective—it’s astute to have De’Lon Grant take on Posthumus and the character’s evil doppelganger, Cloten, but Grant doesn’t create sufficiently distinct figures, in particular failing to convey the darker side of his roles. Cloten is a clown, but one with homicidal dreams, while Posthumus explodes into a sick, macho frenzy once he believes that Imogen has betrayed him. Marya Lowry goes overboard trying to supply menace as the evil queen, while Neil McGarry doesn’t come close to expressing the glorious, psycho-sexual weirdness of Iachimo, who, in an effort to defame Imogen, hides in her bedroom and peruses her body as she sleeps. Here the lack of props works against the production—miming the presence of the trunk that Iachimo pops in and out of comes off as romper-room precious. Even the prop-scarce Donmar Warehouse Lear puts Kent in real stocks.

Brooke Hardman supplies an attractive and feisty Imogen, though she doesn’t come close to exploring the tragic possibilities of the part, including the modulated, melodramatic hysteria in one of the play’s great gob-smacking scenes. Our heroine, disguised as a man, wakes up to find what she believes to be the headless corpse of Posthumus alongside her. Imogen embraces her dead love’s body, smearing herself with its blood—this episode, its horror, absurdity, and majesty, can work, but an actress must be willing to take more emotional risks than Hardman does.

And Cymbeline can cast its Byzantine spell as well if a production takes a chance and trusts Shakespeare more. A little cooperation helps: my rule for critics and audience members is to read a rarely performed Shakespeare play before seeing the performance—it heightens the pleasure and understanding considerably. In writing about the text in Prefaces to Shakespeare, critic Tony Tanner argues that “our pleasure should be tragical-historical-comical-pastoral-romantical; and also, theatrical-magical. Cymbeline, it seems to me, is the most extraordinary play that Shakespeare ever wrote.” The ASP touches on the comical-pastoral-romantical—the rest is left on the cutting room floor.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Actors' Shakespeare Project, Cymbeline, Derek Jacobi, Donmar Warehouse, King Lear, Michael Grandage, drama, romance, tragedy