Theater Review: R. Buckminster Fuller — I Sing the Body Geodesic

D.W. Jacobs’s presentation of the life and ideas of American visionary R. Buckminster Fuller invites you to make your own intellectual structure out of what you have seen—connect Fuller’s dots and you have an image that expands your mental horizons or at the very least ups your powers of analysis and recall.

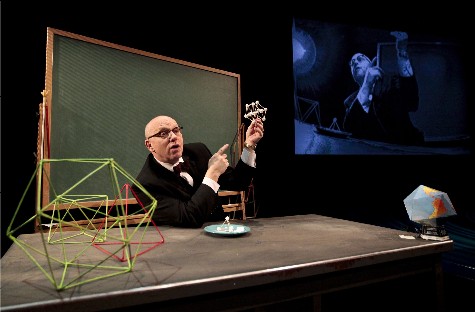

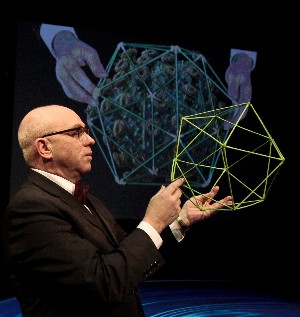

Thomas Derrah (R. Buckminster Fuller) contemplates the mystery of the icosahedron. Photo: Marcus Stern

R. Buckminster Fuller: The History (and Mystery) of the Universe. Written and directed by D. W. Jacobs, based on the Life, Work, and Writings of R. Buckminster Fuller. Performed by Thomas Derrah. Set and Lighting design by David Lee Cuthbert. Video design by Jim Findlay. Presented by the American Repertory Theatre at the Loeb Drama Center, Cambridge, MA, through February 5.

By Bill Marx

Playwright D. W. Jacobs calls this rousing, one-man talk-a-thon dedicated to the futuristic imagination of American visionary R. Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983) a “pileup of ideas.” And that is how the evening comes off, a whole kit-and-kaboodle journey through the capacious life and quirky mind of the inventor of the geodesic dome. At first the script’s brusque zig-zagging from subject to subject doesn’t seem right for Fuller’s life-long dedication to the majesty, beauty, and flabbergasting flexibility of structure: hymns to the magic of synergy jump to family tragedy, paranoid meditations on worldwide capitalist conspiracies give way to smiley peons to mankind’s chances for survival by making more out of less.

Like Walt Whitman, another American genius powered by an expansionist imagination, Fuller contains multitudes, and Jacobs stuffs a lot of them into R. Buckminster Fuller: The History (and Mystery) of the Universe. Even though there is an effective use of multi-media to jazz things up, and the play’s Fuller dances, sings, and even strolls up the aisles from time to time to instruct us on, for example, the fine art of syncing with the earth’s rotation, at times it feels as if you are sliding at supersonic speed around the points of a dodecahedron. At worse, and that isn’t too often, the script feels like a version of the preachy, pick-me-up programming dredged up by PBS during pledge time with Dr. Wayne Dyer or some other other guru of self-improvement pitching the audience, via books, tapes, videos, a happier sense of self. But the play’s Fuller isn’t selling anything but his ideas, which remain fascinating though head-scratching.

What’s more, by the end of the show the burgeoning amount of information, on the nature of Nature, the essence of energy, the pragmatic pizazz of the Platonic forms, the battle between muscle and mind for the future of the world, makes sense because it poses a challenge. Jacobs invites you to make your own intellectual structure out of what you have seen—connect Fuller’s dots and you have an image that expands your mental horizons or at the very least ups your powers of analysis and recall. Infusing the intellectual banter with additional life is an almost childlike spirit of American can-do, an infectious sense that with sufficient application and gumption anybody can figure this stuff out.

At times this invitation to thought points out the inevitable limits of the one-man show—it would be compelling to hear Fuller challenged by a competing interpretation of the universe, especially one that reflects a more acute sense of the horrors of the 20th century. Fuller registers man’s proclivities for fear and greed (and his picture of global corporate control is draconian) but, for someone who sees synergy as the key to the universe, he has a tendency to break things apart into surprisingly simple units.

For example, Fuller tells us that for the ecologically endangered earth to remain viable mind must triumph over muscle. But can mind and muscle be so easily separated? Is there such a thing as pure mind? (Sometimes Fuller comes off as a hip Platonist.) Can the conscious and the sub-conscious be divided neatly? Doesn’t the notion of structure suggest that there will always be tensions (healthy, not-so-healthy) among contraries? And aren’t our corporate overloads thrilled with the idea of doing more with less? The theater thrives on intellectual conflict—it would have been nice to see some brainy sparks fly under Fuller’s dome.

Certainly Thomas Derrah’s wily and wonderful performance as Fuller shows how to balance contradictions creatively: in the play, Fuller comes off as a mix of Horatio Alger, Whitman, and the absent-minded professor, an ornery individualist who pulls up his boot straps in order to re-imagine the universe, a mystical seeker after abstract truth who remains a loving father and family man, a rebel disdainful of all things conventional who never becomes threatening, a scientist who wallows in humanism.

Friendly, self-deprecating, folksy, and breezily eccentric, Derrah gives us a Fuller who patiently explains his complex ideas yet doesn’t forget that the medicine goes down best with some show biz personality. The performer puts his talent for comic timing to good use, especially his arch physicality.

The script’s scatter shot leaps from topic to topic flatten some of the emotional contours of Fuller’s life—at one point the designer mentions that his beloved wife is ill and then quickly moves on. Derrah chooses to bounce through the traumas and depressions, perhaps indicating that Fuller’s personality compensates for metaphysical down time by maneuvering his energetic mind onto new projects to improve or protect “this beautiful little spaceship called earth.” It is difficult not to become a more awe-struck traveler after watching Bucky’s speculative spiel.

Tagged: American Repertory Theater, D.W. Jacobs, R. Buckminster Fuller, The Hisory (and Mystery) of the Universe, drama