Film Commentary: “Inside Llewyn Davis” — Another Perspective

Among the important things the filmmakers get right — the elemental pissiness of a scene that is far smaller than it is envisioned by the narcissists who once occupied it.

See that kid sitting back at the bar

Picking up a storm with a Martin guitar

Poor fool thinks he’s going to be a star

But he’s just another loser like me

Losers, losers, some are raggers, some are bluesers

Making disco sounds in a HoJo lounge

With a bunch of other losers like me…

“Losers,” Dave Van Ronk

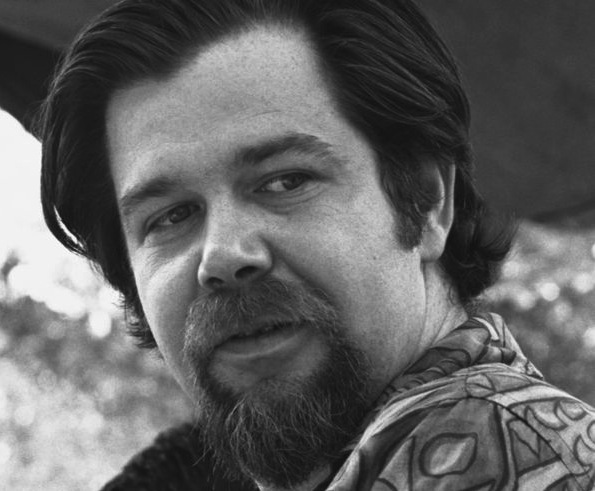

By Jackson Braider

All contrarians aside — Sorry, Suzanne! Sorry, Christine! — the Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis explores with considerable accuracy the Greenwich Village folk scene circa 1960-61. It follows the rocky trajectory of one Llewyn Davis, a fictional, composite folksinger who devotes himself in the film to making traditional music relevant again. As a participant in the Greenwich Village singer/songwriter scene twenty years after the film’s mythic date, I witnessed, in the flesh, both the picture as drawn by Dave Van Ronk in his memoir The Mayor of MacDougal Street (a source for the film), and what is portrayed in the Coen Brothers’ narrative. What else to say? They are both true.

Let me start with the obligatory disclaimer: I opened for Dave Van Ronk back in 1995 in the Westborough coffeehouse once known as the Old Vienna. As a one-time singer/songwriter, I will freely admit that this was the highpoint of my folkie career, and no one will ever be able to take it away from me. I held my own in the course of my set; Van Ronk, of course, rocked. “You can see I spend a lot of time tuning,” he said to the audience that night. “That’s because I hunt down the one string that’s out of tune, then tune all the rest of them to it.” The crowd roared their approval — another classic rim-shot/cymbal crash from a master of folk performance.

One of the problems with the artistic commentary on this subject is how frequently it features what the commentator would have made the film — or the song or the album or the book or the poem. To put is another way, such commentary almost always dwells on the film/book/album/poem/twitter said writer would have created — had he or she been willing to devote the time and effort to such a project. Case in point: this column.

Meanwhile, much of the commentary surrounding the film so far has turned on questioning how closely the Coen Brothers got the facts of the Greenwich Village scene right — let’s call this the trail of veracity. David Haglund at Slate.com, for example, offers up a who’s who of characters in the film possibly based upon persons living or once-living, as well as a list of events that may (or may not) have occurred. Others parse the film in terms of its lack of veridicality.

Missing in both instances is acknowledgement of the Coens’ choice of narrative genre: the epic myth. As any folklorist or mythologist will tell you, the myth is a vehicle that is designed to deliver not facts so much as higher truths that resonate with the formative beliefs that define the culture. And Inside Llewyn Davis is rich in such higher truths. Who are the real bearers of tradition, for example? Who are the performers that work with traditional material but want to interpret it for contemporary listeners? Who are looting the past? Who are the pillagers trawling their way through traditional materials in order to create something vital and new?

The Coen Brothers introduce us to all of these types in the course of the film. Among the important things the filmmakers get right — the elemental pissiness of a scene that is far smaller than it is envisioned by the narcissists who once occupied it. I, for example, know that I did not get the attention my artistry and talent deserved. As a result, I can effortlessly reach back and retrieve ancient resentments and slights. Among noted acidic open-mic experiences (though this comment, happily, was not aimed at me) — “You with the guitar! Put your hands up and slowly step back from the microphone!”

The world of the Gaslight and Folk City — or later, the Speakeasy — was really no bigger than a village, with one to two hundred residents vying for the main stage in hopes of getting that big weekend gig. Some were pretty; some had talent; but most, quoth Van Ronk himself, were losers.

And so the Coen Brothers nail an essential aspect of the New York folk scene: there were little difference between six of one and a half-dozen of another. Little difference, but many approaches. As the film reveals, the New York folk world in the early ’60s divided itsel into three parishes. In the first and highest parish were the tradition bearers themselves, bluesmen and aging fiddlers, lured from their obscurity as postal workers and janitors at hot-sauce factories to reclaim their tradition-bearing roles. The one-time blues artist Sun House somehow managed to wrap his palsied hands around a guitar neck again in the early 60s, only to be introduced by one Harvard undergrad as “the epitome of the cool Negro.”

In contrast, there were folk players of the time, claiming to represent Tradition, who were not necessarily interested in recreating traditional performance. What they wanted was — what? — to make the old time music palatable. Thus the recreation of Peter, Paul and Mary’s “500 Miles” (written by Hedy West) in the film. Then there are Llewyn Davis’s (Oscar Isaac) own brand of performance; when he plays “The Death of Queen Jane” for the club owner in Chicago he knows he’s doing it justice. Only a hard-and-true folkie would actually conceive of presenting the climax of a sixteenth century English ballad in an unadorned sotto voce. The screwiest thing about that? Done right among the right kind of people, you can hear the silence. Sometimes, of course, the pursuit of the dramatic in the people’s music can also go, oh, so terribly wrong.

Which leads me back once more to all the bitching and whining about how Inside Llewyn Davis misrepresents Dave Van Ronk. Yes, there are some elements of Dave in Llewyn — they both get beaten up once (or twice). Roland Turner (John Goodman) may be the stand-in for one Doc Pomus, but I feel in my bones that his rants voice Van Ronk’s profound sense of musical eclecticism, combined with an ironic lack of musical curiosity that is frequently displayed by the folkies.

Here’s the thing that everyone who knew or knew of Van Ronk — he was a man of great resourcefulness, spirit, and fun, a lickity-spittle virtuoso of a fingerpicking, ragtime, old-time guitar. Unlike Davis, Van Ronk always knew who he was and where he stood.

And that’s why Van Ronk’s “Losers” is so inspired. It’s not only true; it’s goddamned funny.

Jackson Braider Jackson Braider is an independent radio producer and writer based in Boston. A longtime music journalist, Braider earned his masters in folklore and mythology at UCLA and participated in the New York singer/songwriter scene in the 1980s. He had two songs published in Fast Folk: “The Four Seasons” in 1984 and “Paris by Night” in 1988. Both are available digitally at Smithsonian Folkways.