Film Review: Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project — The Art of Restoration, Around the Globe

Director Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project is committed to doing the indispensable work needed to save examples of damaged but worthy landmarks of cinema.

By Rob Ribera

Last week, the Library of Congress released the findings of their exhaustive study on the state of American silent film from 1912-1929, and the results were devastating, if not surprising. Most American silent films from the period are gone. A little more than 3,000 of the 11,000 films released now survive. Half of those that do survive are incomplete or in poor condition. The majority of films are gone. Not missing, not sitting in a vault because they haven’t yet been digitized in our latest media transition. Gone. There are many reasons for this, ranging from neglect and destruction to the fragile nature of early nitrate prints. This was yet another stark reminder that parts of our film heritage are disappearing. This is not a new issue here, and there have been some great strides toward restoring and preserving our precious celluloid heritage. The cinemas of Africa, Senegal, East Bengal, South Korea, and other countries around the globe have not been as fortunate at finding champions. Luckily, they have the formidable Martin Scorsese on their side.

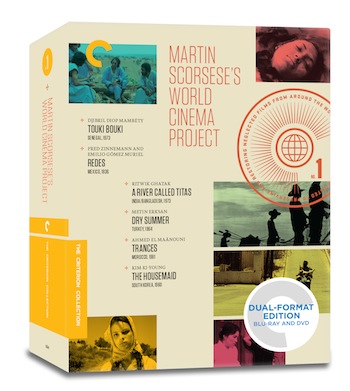

The Criterion Collection has just released Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project, which collects six of the films that have been restored under the aegeis of the WCP since 2007: Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Touki Bouki (1973), Fred Zinnemann and Emilio Gómez Muriel’s Redes (1936), Ritwik Ghatak’s A River Called Titas (1973), Metin Erksan’s Dry Summer (1964), Ahmed El Maânouni’s Trances (1981), and Kim Ki-Young’s The Housemaid (1960). All of the films come with an introduction by Scorsese, interviews with many of the filmmakers, visual essays, and other bonus materials. Though the individual releases are not chock full of extra material, the fact that this box set exists is a blessing for any lover of cinema. I do not say this glibly—Scorsese is perhaps the most important face in film restoration today. He is a tireless champion of this kind of preservation, and the World Cinema Project has done most important work to help save unknown but worthy landmarks of cinema. Each of the films presented in this box set is worth our attention—forgotten classics that will hopefully now receive the necessary critical and public appreciation.

For me, Redes is the standout release in the set. Paul Strand’s Modernist photography, paired with the direction of Fred Zinneman and Emilio Gómez Muriel, can only make us wish that Strand had done much more with the movie camera. The film is a wonderful addition to his cinematography for his own film Manhatta and Pare Lorentz’s The Plow that Broke the Plains. Funded by the Mexican government in 1935, the story revolves around a man who struggles to survive in a small fishing community on the Gulf of Mexico. He fights to find employment, stands up to local politicians, and begins to organize the laborers, all with the hopes that he will come up with the resources to pay for his son’s medical treatment. There are lively, beautiful, playful images throughout, including those of hopeful fisherman throwing nets into the ocean (the fish leaping into the air, their scales glinting with the midday sun) and stark close-ups of the faces of men who have struggled to survive for far too long. The scene where a man grabs a shovel from the gravedigger so he can pour the dirt over his son’s body is one I will not soon forget.

Ritwik Ghatak is another figure who deserves more attention. A teacher and mentor to other filmmakers in India, including the famed Satyajit Ray, Ghatak did not, as Scorsese notes in his introduction, get his due during his lifetime. Like Redes, A River Called Titas is a beautiful film about the lives of fishermen, though on the other side of the world. The film’s ambitious scope, its crisp black and white photography and stirring music, has the substance of an epic but watching it comes off as an intimate rather than bloated experience.

The Housemaid is a perfect example of the powers of restoration. Some of the original reels were missing. Luckily, acceptable replacements were found in the 1990s, but they had English subtitles burned right into the celluloid. With the help of the Korean Film Archive, the World Cinema Foundation was able to digitally remove the subtitles and bring this intense drama back pristine condition. Incredibly, as Kyung Hyun Kim writes in his liner notes for the film, hatmakers and chemists destroyed many Korean film prints in the 1960s and 70s. The ‘worthless’ celluloid was used to keep straw hats sturdy and stylish, or the valuable silver in the film strips was extracted. A desire to not waste unfortunately laid waste to many South Korean masterpieces.

There is much more to be found here. Touki Bouki, the Senegalese film, reminds us that $30,000 is plenty enough money to create a masterpiece. Director Djibril Diop Mambéty should be placed right alongside Ousmane Sembène as one of the great filmmakers of an African Golden Age in cinema. Dry Summer is the restoration of the Golden Bear winner from the 1964 Berlin Film Festival, one of the few films that Metin Erksan made in his short career before withdrawing from the industry in the late 1970s. Trances is a wonderful music documentary, focusing on the Moroccan band Nass El Ghiwane, that was released just a few years after Scorsese’s concert film The Last Waltz. It is no surprise that the director was drawn to the music here—especially when we hear the band, particularly its song “Ya Sah,” which was an influence on Peter Gabriel’s work on The Last Temptation of Christ. This beautiful film was the first movie the World Cinema Project restored. As Scorsese recalls in his introduction to the film, “It was a good place to start.”

Cinema itself is only a bit more than a century old, yet we have gained and lost so much in that time. Films have been thrown away and rediscovered. Seismic shifts in technology have thrown the art and industry upside-down a number of times. Across the globe there have been vital acts of restoration and preservation in the face of encroaching oblivion. With the release of The Criterion Collection box set, The World Cinema Foundation and Martin Scorsese have put pressure on the wound. Every one of these films, just six of the near two dozen that have been restored so far, is vibrant and alive.

If the amount of lost and damaged films is disturbing, there is a promising number to be found. Emblazoned on the side of this indispensable box set is the number 1, which promises that this is just the first in a series of World Cinema Foundation sets. We can only hope.

Rob Ribera is a filmmaker and music video director in Boston. He is the co-creator of the music website Sleepovershows.com, and is currently working on his PhD.in American Studies at Boston University.