Film Review: Essential Francois Truffaut — “The Green Room” and “The Man Who Loved Women”

The Museum of Fine Arts’ retrospective of the films of Francois Truffaut offers an opportunity to see some rarely screened late works by this master of 20th-century cinema.

The Films of Francois Truffaut at the Boston MFA, through December 28.

The Man Who Loved Women / L’homme qui amait les femmes and The Green Room / La chambre verte

The Man …, Saturday 1 p.m. in Alfond Auditorium

The Green Room, Saturday 3:30 p.m. in Alfond Auditorium, Sunday 10:30 a.m. in Remis Auditorium

“The Green Room” has an extraordinary unity, perhaps because most of its scenes were shot within a large, decaying house in Honfleur, Normandy.

By Betsy Sherman

As the month-long Francois Truffaut retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts goes past the halfway mark, it offers some rarely screened late works by this master of 20th-century cinema. Nearly twenty years on from the director’s nouvelle vague classics The 400 Blows and Jules and Jim, films such as the 1977 The Man Who Loved Women, an intriguing comedy that playfully examines some of his personal and artistic proclivities, and the 1978 The Green Room, an achingly affecting drama that ranks among his finest works, deserve to be seen on the big screen.

It has been said that the history of cinema is that of boys filming girls. Truffaut, known for working with beautiful actresses and having affairs with some of them, acknowledges the fuzzy area between desire and obsession in The Man Who Loved Women (co-written with Michel Fermaud and Truffaut’s longtime assistant Suzanne Schiffman). The movie places the Male Gaze, or, at least, one gazer, under a microscope. Bertrand, played by the hatchet-faced, elegantly compact Charles Denner (Burt Reynolds played the lead in the Hollywood remake), has sophisticated manners, great posture, impeccable diction and a pervy mind (old school pervy, that is, compared to the protagonist of this year’s Don Jon, Bertrand is downright Victorian). Although the movie is presented in flashbacks after Bertrand’s untimely death (hence the past tense in the title), most of it features Denner’s gravel-mixed-with-honey voice-over, in which he recounts his taxonomy of the female attributes he prizes. The camera, with smooth formalism (no shakey-cam fake spontaneity for Truffaut) presents us with a parade of women’s legs, from swinging skirt (knee-length, no minis) to high heeled sandals, walking briskly along to it-doesn’t-matter-where. Bertrand can’t seem to stick with one pair for very long; this has something to do with his distant, promiscuous mother. Denner is a delight, and the movie gives nice roles to an array of actresses as the objectified women who stride in and out of Bertrand’s life (and return to mourn him at his end).

In the autobiographical 400 Blows, young Antoine Doinel builds a bedroom shrine to his idol Balzac; the candle he lights sets the cardboard enclosure on fire. The apotheosis of Truffaut’s impulse to pay homage to the artists, books, movies and music he loved is The Green Room. The screenplay is based on Henry James’ stories “The Altar of the Dead” and “The Beast in the Jungle,” yet reflects the director’s often expressed concerns about honoring memory and creating something for posterity. Truffaut knew that the film, about a World War I veteran deeply shaken by the deaths of his comrades and of his young bride, would not be a moneymaker. He therefore shot it on a low budget and on a tight schedule, and played the lead himself (he had acted in his own The Wild Child and Day for Night, and for Steven Spielberg in Close Encounters of the Third Kind). The brilliant cinematographer Nestor Almendros, in his book A Man With a Camera, wrote that in spite of the morbid themes, the film’s shoot was a joyful one.

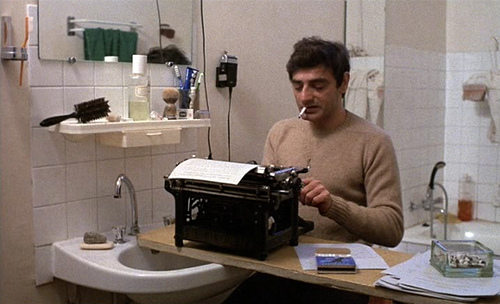

In contrast to the main character in The Man Who Loved Women, Julien (Truffaut) takes monogamy to the extreme. An obituary writer for a moribund newspaper in provincial France, he lives a spartan, quiet life in the company of his elderly housekeeper and the deaf-mute boy for whom she serves as guardian. He keeps an entire room as a shrine to his late wife, who had waited for Julien throughout the war but who died a few months after they were wed. At an estate sale, he encounters Cecilia (Nathalie Baye in her breakthrough role), a young woman of similar temperament. Each finds they can speak freely to the other of feelings no one else would understand. However, there is no place in Julien’s heart for a woman other than Julie. When he’s locked in at a cemetery after hours, he comes upon an abandoned chapel; he later receives permission to renovate the chapel as a memorial, illuminated by candles, to “my dead.” Cecilia becomes a partner in this mission that can only lead to more death, more grieving.

It is evident that Truffaut worked with complete independence on The Green Room. The film has an extraordinary unity, perhaps because most scenes were shot within a large, decaying house in Honfleur, Normandy. The visual scheme, featuring veiled faces, gloved hands, dark stairways, wrought-iron doors, and mirrors that capture mere glimpses of the players, makes the viewer yearn to find out what’s being hidden. If not for the automobiles, one would think this 1920s story took place in the 19th century. The pace is somber and austere. Truffaut knew when he conceived the film that he would use music by Maurice Jaubert, a composer who scored many French film classics from the 1930s and who had been seriously wounded in World War I. The stately, stirring score is just one of the film’s rewards.

Throughout his career, Truffaut embedded references from films he loved into his own. Fittingly, The Green Room contains so many talismans that one could play reference bingo. Most obviously, there’s the Hitchcock of Vertigo and Rebecca, and an aura of Edgar Allan Poe. There’s the influence of silent film in general (in the World War I battle footage that haunts Julien), but in particular of Carl-Theodor Dreyer and Abel Gance. In addition, Truffaut’s films are linked by direct or indirect reference to his own earlier works—in this one, for example, there’s the name Julie (common to several Truffaut heroines), and a photo of a World War I veteran that’s actually Oskar Werner in Jules and Jim. Julien’s tutelage of the deaf-mute boy recalls the Truffaut character’s tutelage of the feral boy in The Wild Child. The chapel shrine is adorned with images of idols such as Oscar Wilde and Jean Cocteau. These inclusions don’t detract from the story but, by adding an extra layer of reverence, contribute to its richness.

By all means check out these Truffaut offerings, so that maybe the MFA will add a coda featuring two of the director’s movies they have overlooked: the zany black comedy Such a Gorgeous Kid Like Me, and my favorite Truffaut movie, Two English Girls (the European cut, please!).

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in Archives Management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Nice piece, Betsy, about two Truffaut movies nobody much sees or talks about.Concerning the autobiographical component of The Man Who Loved Women: Truffaut, an obsessive womanizer, slept with every single leading lady in his movies until The Story of Adele H., Isabelle Adjani said “No,” only to succumb soon to another obsessive girl chaser, Warren Beatty.

Among the dead on the wall in The Green Room is Henry James himself, whose novellas, as Betsy indicated, inspired the movie. One correction: Jean Cocteau couldn’t possibly be on the wall since he died in 1963.