Book Review: Martin Cruz Smith’s “Tatiana” — More than a Thriller?

After 2010’s too spare “Three Stations,” fans old and new will find Martin Cruz Smith back in full form with “Tatiana,” creating a taut, subtle, often darkly funny and even moving tale.

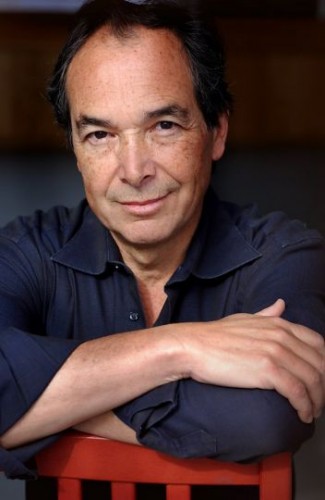

By Eric Grunwald

In and of itself, Martin Cruz Smith’s latest mystery thriller, Tatiana, is a welcome addition to the acclaimed series which began back in 1981 with the dogged Arkady Renko taking on both corrupt communists and over-greedy capitalists in Gorky Park. Fans old and new will find Smith back in full form after his too spare Three Stations, creating here a taut, subtle, often darkly funny and even moving tale. Yet despite its strengths the novel leaves the reader with a sense of disappointment, of an opportunity missed.

“It was the sort of day that didn’t give a damn,” Tatiana begins. “Summer was over, the sky was low and drained of color, and dead leaves hung like crepe along the road. Into this stillness dashed a cyclist in red spandex, pumping furiously, taking advantage of the flat terrain.” The cyclist is an interpreter, and his cryptic – all but hieroglyphic – notebook finds its way into the hands of the title character, an outspoken journalist, who soon falls from her balcony, an apparent suicide.

Renko enters the scene during a protest at the foot of that apartment building, the marchers protesting not only Tatiana’s suspicious death but also the fact that the police seem to have lost her body. “What caught Arkady’s attention,” Smith writes, “was that a neighbor had heard her scream. Suicide usually took concentration. People who committed suicide counted pills, stared in fascination at their pooling blood, took the high dive in silence. They rarely screamed.”

And so continue the mysteries that have led the incorruptible Renko through the ebbs and flows of power and money in the former Soviet sphere, with stories set as far afield as Siberia, Havana, and Chernobyl. Renko is in fine form here, too, with his obsessive, reckless pursuit of justice, his cleverness, and his mordant, self-deprecating wit. Early on, for example, a Moscow gangster asks him, “Is it true you don’t carry a firearm? For what reason?”

“I’m lazy,” answers Renko.

“No, really.”

“Well, when I did carry one I hardly ever used it. And it makes you stupid. You stop thinking of options. The gun doesn’t want options.”

“But you’ve been shot.”

“There’s the downside.”

Renko soon gets ahold of the notebook and begins to bear the punishing brunt of its ownership as the story moves to the enclave of Russian territory west of the Baltic states that was once Prussia: “The rain was miserable. The mud was miserable. Tomorrow would probably be miserable. ’Kaliningrad.’ Maxim spread his arms to welcome Arkady.”

Aided by his oft-drunk partner, Victor, and by his wayward semi-ward, Zhenya, a chess genius bent on joining the army, and accompanied by a cast of the usual thugs, corrupt or uncaring bureaucrats, strong, smart women, and even a suspect poet, Renko braves the headwinds to decrypt both the notebook and Tatiana’s death.

Smith is great at conjuring up sudden intimations of intimacy, as when Arkady listens to old cassettes of Tatiana recordings of the cases she’s covering and comes to the last one: “At first he thought it was blank and then he picked up her low, soft voice. ‘People ask me is it worth it.’ A pause, but he knew that Tatiana was there on the other side of the tape. He could hear her breathing.”

Yet here is where we begin to run into trouble. Smith clearly sets up the book as homage to Russian journalist and human rights activist Anna Politkovskaya, an outspoken critic of both the Chechen conflict and Vladimir Putin who was shot execution-style in the elevator of her apartment building in Moscow in 2006, a murder that still remains unsolved.

From the character’s name, Tatiana Petrovna, to her personality—she is described as “fearless” and “independent” in her criticism of both Russian and Chechen leaders—even to both women’s being invited to participate in the hostage negotiations in the Moscow theater hostage crisis in 2002, we are clearly meant to see her as representing Politkovskaya.

And Tatiana’s editor tells Renko early on, “You and I know that our demonstration was about more than Tatiana. It was about all journalists who have been attacked. There’s a pattern. A journalist is murdered; an unlikely suspect is arrested, tried and found not guilty. And that’s the end of it, except we get the message. Soon there will be no news but their news.”

Our expectations are further heightened when Renko visits the university “and could not help but measure his progress in life against the precocious student he had been. What promise!” But “Somehow, he had wandered. . . . Crimes that displayed planning and intelligence were all too often followed by a phone call from above, with advice to ‘go easy’ or not ‘make waves.’ Instead of bending, he pushed back, and so guaranteed his descent from early promise to pariah.”

One of the great things about fiction, as writers such as Hillary Mantel have shown, is that it encourages us to reimagine history, to offer new explanations of murky events or characters, even, when writing about current events, to inspire justified action or outrage. It need not be programmatic, but it does need to be willing to go for high stakes.

Oddly, though, while Arkady does have to do some pushing, even upon threat of death, the book doesn’t deliver on its own early promise. Even as Smith sets up an ambitious plot with the potential to reach high and wide, his recent penchant for understatement, possibly born of a fear of indulging in formulaic melodrama, narrows his focus.

Perhaps that’s a bit of a spoiler, but when a book sets itself up to be more than just a thriller and mirrors real people who have been murdered; when not only Anna Politkovskaya but also a lawyer who had investigated many of the abuses she had alleged is killed during the trial of her suspected killers; when one of the suspected murderers is an FSB officer; when a politician is rumored to have ordered Politkovskaya’s death; when the International Federation of Journalists has launched a database of over three hundred deaths or disappearances in Russia since 1993; when the investigations of these murders always somehow lead nowhere; when, in short, journalists can be killed with impunity and there is clearly something rotten in Moscow, then this is not the occasion for excessive restraint.

Late in Tatiana there comes a point when Renko, still only semi-armed, must risk getting very close to the real bad guy in order to take him down. By the end of the book, one is left wishing Smith had taken a similar risk.

Eric Grunwald studied Russian and East European history at Stanford University and later was managing editor of Agni. He now teaches writing at MIT and is at work on a novel. www.ericgrunwald.com

Tagged: Eric Grunwald, fiction, Martin Cruz Smith, Mystery thriller