Fuse Theater Review: “The Cocktail Hour” — A Pick-Me-Up for Waning WASPS

With the 1% rapidly vacuuming up the resources of the upper and middle classes, A.R. Gurney’s comic vision of the tipsy idle rich, shorn of cares and criminality, floats completely free of reality.

The Cocktail Hour by A.R. Gurney. Directed by Maria Aitken. Staged by the Huntington Theatre Company at the Boston University Theatre, Boston, MA, through December 15.

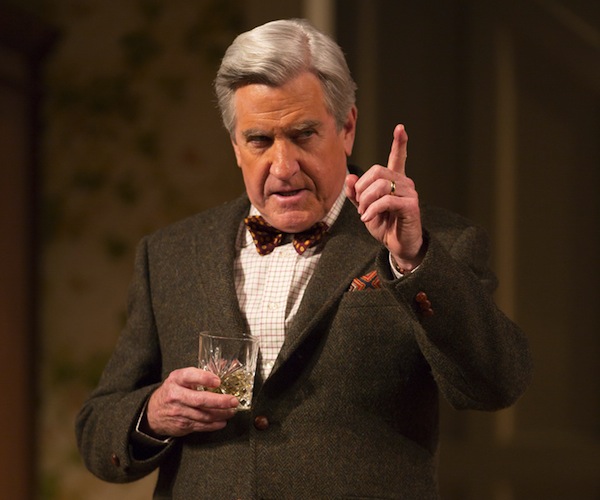

Richard Poe as Bradley in the Huntington Theatre Company production of “The Cocktail Hour.” Photo: T. Charles Erickson.

By Bill Marx

Nostalgia is one of playwright A.R. Gurney’s favorite topics, and my curiosity about a hankering for the past was one of the reasons I went to see The Cocktail Hour. I reviewed the Huntington Theatre Company’s production of Gurney’s The Dining Room in 1982 (as well as the HTC’s The Snow Ball in 1991), and I wondered how his comic take on the decline of the WASP would fare after the arrival of another generation. God knows what Generations X, Y, and Z make of Gurney’s ambivalent fuss about the collapse of genteel white-bread wealth and manners: my guess is that they probably find it inscrutable, as bizarrely antique (to them) as black and white movies. But perhaps, given the passage of time, Gurney’s genial vision of an America slowly slipping out of the hands of the “right people” might be more compelling, or at least reassuring, as the country becomes more multi-cultural. Maybe Gurney ages well.

He doesn’t. Thirty years ago I found his version of the fall from grace of the elite featherweight class facile, and its commercial superficiality hasn’t changed its spots. Now, with the 1% rapidly vacuuming up the resources of the upper and middle classes, his vision of the tipsy idle rich, shorn of cares and criminality, floats completely free of reality. (Writer Louis Auchincloss trod over some of the same genteel ground, but he understood that larceny was mother’s milk to the nation’s ruling moneybags.) Gurney isn’t interested in generating laughter by digging into the innards of American privilege and its accumulation of wealth or probing deeply into attitudes on race, class, and success. The plot of The Cocktail Hour suggests (ironically?) that the laughs lines will be connected with the script’s exposure of uncomfortable topics, its revelation of disturbing relationships among the upper crust. But this is “A Long Day’s Journey into a Cocktail Hour” — the characters may be boozers, but the dramatist remains resolutely sober, maintaining polite and upbeat proceedings for the discreet bourgeious in the audience. No one’s feelings, no matter how reactionary, will be hurt.

The plot is simple enough: it is the 1970s and son John, who works in publishing but is also a semi-successful playwright, visits his superannuated parents in Buffalo, NY, with a time bomb — a new script that, we are told repeatedly, reveals disagreeable family secrets. John is frequently castigated as the family troublemaker, but, ever dutiful, he wants his parents’ blessing or he will not stage the play. Patriarch Bradley and matriarch Ann, downing martinis as they wait (and wait…. and wait) for dinner to be served, put the kibosh on the idea. Daughter Nina arrives and takes the side of the oldsters against John’s attacks, which generally revolve around his belief that he wasn’t sufficently loved. That is about it regarding dramatic explosions, anarchistic zingers, and real revelations: John’s barbs are either undercut by his hypocrisy or childishness. He is a rebel without a clue, not even able to question the family’s thinking about race, which are low hanging fruit.

Instead of exploring social contradictions or personal traumas, The Cocktail Hour revolves around (and around) speculation about John’s script and what it contains. It is not a sufficient comic hook and director Maria Aitken knows it. She tries, futilely, to suggest that some sort of Pirandello-lite layering is going on: the play we are seeing is John’s play! But that means that the script is a real bomb, absolutely toothless aside from its intimation that his parents are alcoholics, so all the angst is much ado about nothing. Pirandello’s theatrical games are rooted in some sort of horrific truth and/or shame that the characters are willing to distort reality to hide. But there is no gnawing darkness in the lives of Gurney’s characters — they are not able to look deeply into what is wrong because, well, nothing is amiss that a little gumption can’t cure.

James Waterston and Maureen Anderman in The Huntington Theatre Company production of “The Cocktail Hour.” Photo: T. Charles Erickson.

And I think that is the point. Despite John’s claims, he isn’t on the hunt for the truth. That might actually shake things up. The Cocktail Hour is about repackaging the good old American virtue of self-reliance — Bradley doesn’t quote (or mis-quote) Emerson for nothing. By the end of the play the characters have learned that they must reject dependence (even on maids) and be on their own — forget clinging to the past, wanting the family to stay together forever, remaining a pampered, charity-minded housewife, staying in a job you hate. Get-up-and-go doesn’t seem to do much for the servant class in the play, but if you are white and well-off it does wonders. Cue applause …

Another reason I went to The Cocktail Hour is that I really liked Aitken’s production of Harold Pinter’s Betrayal last season and I hoped that she could import some of that edgy sensibility into a staging of this very different script. Can Gurney’s mainstream characters be made sharper, more mysterious? The verdict, based on this outing, isn’t encouraging. Aitken’s turn to Pirandello for needed heft is a misfire, while the dialogue’s banter is too soft and staidly sit-comish to suggest that John and his imbibing family live lives of quiet desperation. The cast is solid, but only Maureen Anderman as Ann provides some of the quirky line readings necessary to make her character memorably askew. Richard Poe is far too one-note blustery as Bradley to suggest there is anything behind the figure’s megaphone facade. James Waterston makes for a pretty irritating John, to the point that the character’s turn toward emotional sympathy isn’t convincing. Pamela J. Gray’s Nina is pitched a bit too high at times.

At the end of The Cocktail Hour, Bradley and John agree that plays should be celebratory. Roll over Aristotle, tell Brecht the news. That cheerily commercial idea explains why Gurney’s nostalgia about waning WASPs might appeal to theater audiences today. Fuse Film Critic Gerald Peary noted recently that there is current a trend in films that features “individual heroes battling adversity.” The aging, upper middle class demographic that regularly attends major theaters is hungering, during a period of rapid economic and cultural change, for reassurances that the magic tricks of the old days still work, which may explain the turn in the repertoire to plays with a conservative bent. But theater that is really worth celebrating redeems us from that kind of easy redemption.