Book Review: “Lessons from Sarajevo” — Talking About What War Means

In this powerful book, Jim Hicks explores a collection of narratives about the experience of war in many genres and a wide range of media that eschew the sentimental.

Lessons from Sarajevo: A War Stories Primer, by Jim Hicks. University of Massachusetts Press, 192 pages, $22.95.

By Ellen Elias-Bursać

Anyone who writes or speaks about war knows how difficult a subject this is to talk about with students. Jim Hicks has taught a course on war stories at UMass Amherst for many years, and in the process he has assembled a remarkable collection of visual materials, reading assignments, films, graphic novels on the subject. Furthermore he has built up a method for approaching war narratives that permeates this book. It started for him with a good question, as so many endeavors do. He describes a conversation with a friend who had always been puzzled by literary criticism. She couldn’t understand how literary criticism benefits teachers and scholarship. “What are we left with that wasn’t there before?” Hicks spent a decade thinking about the question and throughout the book he addresses aspects of his response. His analysis begins with him pointing out that understanding how war stories are told may be necessary in order to arm ourselves against them.

The course and the book grew out of time he spent in Sarajevo in the late 1990s, and took shape in classrooms where some of his students were war veterans while others were victims of a war, as is the case in so many classrooms all over the United States.

As he guides us through the course, Hicks takes us through the transformative sequence he has built for his students and for himself, a search for the kind of complexity one needs in order to think seriously about what and how war means. Hicks argues that much of what is written, said, photographed, and filmed about war is still shackled to an 18th century sentimentality, which Hicks traces to Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality. He takes us from there through the work of sentimental novelists and shows that, even today, the photographs on the covers of news magazines emphasize a voyeuristic sympathy that allows observers to simplify wartime suffering in the name of an abstracted concern.

The narrative of Lessons from Sarajevo is woven out of digressions, a series of loops and detours that take us through a sinuous sequence of visions, expressions, and explorations of war. Its themes are so beautifully laid out via juxtapositions and parallels that one begins to feel a little guilty at the pleasure there is to be had in reading the book despite its painful subject.

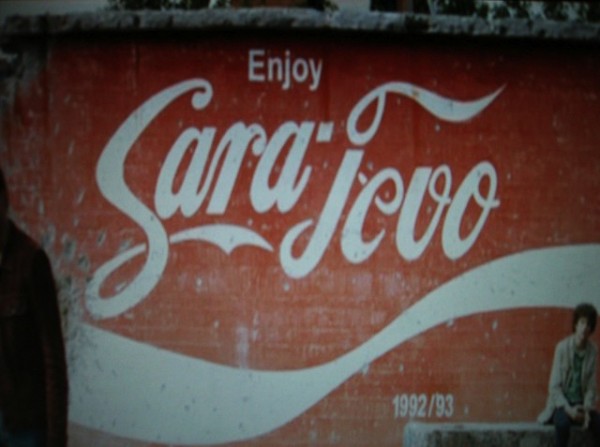

Hicks steers us from one example to another—the printing of Sara-Jevo [Coca Cola] art postcards in besieged Sarajevo, the stories from US soldiers in Iraq, the staging of Civil-War photographs, a graphic novel about Goražde under siege, accounts of Abu Ghraib, Scilingo’s testimony of the Argentinian atrocities, war-related art installations. He teaches through these examples just how crucial art and literature are to any serious consideration of war as a subject, or how to understand what it means to be a victim, or how to fight back against aggression with art.

The starting point is an exploration of the constraints of narrative: “the limitations on knowledge caused by perspective and narrative positioning” and how these “haunt our representations of war.” He is out to do more than examine war stories. He seeks to bring about change. To set the stage he asks: “Where then, as we survey the field, do we find models, stories that do not fall into the trap of giving easy, outdated, and sentimental definitions of their subject?”

His answer is to bring us narratives that do not fall into the sentimentality trap. He champions complication: “We’ll need the complex thinking of artists like these to identify and explore our social rigging, whether historical, actual, or potential. It would do a disservice to these rich, complex, and nuanced stories to reduce their strengths to a sound-bite conclusion.”

And he finds for us, teachers and other readers, a collection of narratives about the experience of war in many genres and a wide range of media that can be used to deepen our own understanding or as classroom material. In his choices he has been guided by the rule of thumb that, “War stories today should be judged on whether, and to what extent, they deny us the easy way out, and make it impossible for us to see the positions of victim, aggressor, and observer as immutable, assigned in advance.”

The thoughtful elegance with which Hicks meanders with us through his stories, images, films is precisely what makes it a pleasure to read a book on how to speak about and teach about war.

Ellen Elias-Bursać has been translating novels, stories, and nonfiction by Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian writers for the last twenty years. She has translated three books of David Albahari’s writing: Words Are Something Else, 1996, awarded the AATSEEL Award in 1998, for best translation from a Slavic or East European language; Gotz and Meyer, 2004 (Britain) and 2005 (US), awarded the National Translation Award by the American Literary Translation Association in 2006; and Snow Man (Canada) in 2005. She has also translated writing by Antun Šoljan, Dubravka Ugrešić, and Slobodan Selenić. She has co-authored a textbook for the study of Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian with Ronelle Alexander, and has written a study on poet Tin Ujević and his work as a literary translator.