Classical CD Reviews: Harmonia Mundi Serves up First-Rate Performances of Schubert and Elgar

Harmonia Mundi has, of late, released a series of excellent Schubert albums.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

There’s no shortage of Schubert recordings on the market, but with over a thousand pieces to his name it’s inevitable that some of them turn up on disc more often than others. Harmonia Mundi has, of late, released a series of excellent Schubert albums, from Paul Lewis’s acclaimed accounts of the late piano sonatas to Matthias Goerne’s multi-volume survey of the lieder. Their most recent disc, featuring Pablo Heras-Casado leading the Freiburger Barockorchester, features energetic and lively accounts of the Symphony no. 3 in D major and Symphony no. 4 in C minor, both written when Schubert was in his mid-teens.

The sunny Third Symphony uncannily foreshadows the mighty Ninth (though, of course, on a far smaller scale): the slow introduction of the first movement introduces the important motivic material of the subsequent sonata-allegro section and the breathless finale comes on the heels of two lilting middle movements that ooze charm and warmth.

The Fourth turns up with somewhat greater frequency than the Third on concert programs and, though less than a year younger than its predecessor, it feels like it was written by a much more mature composer. Part of the reason is that Schubert – much like Mozart and Beethoven – knew how to take full advantage of the dramatic possibilities of the minor mode and he did so here. Another is that its musical materials are far more substantial than the Third’s – the Fourth runs a full third longer and contains a big, sonata form finale as well as an expansive slow movement.

Heras-Casado, a young conductor who tends to pull off the difficult-to-achieve blend of charisma and insightful musicianship, draws appropriately youthful-sounding playing from the Freiburgers: the Symphony no. 3, especially, is light and tripping. He doesn’t try to plumb too deeply into the Fourth, but, rather, lets the music speak for itself, and, as a result, there are some wonderful, striking moments (such as the delicate blend of instrumental colors in opening of the finale). On the whole, it’s a brilliant disc that presents two less-well-known pieces of Schubert’s in an idiomatic light and makes one look forward to the next release from the Heras-Casado/Freiburger pairing.

*****

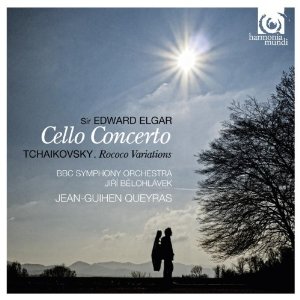

Elgar and Tchaikovsky aren’t two composers who often share the same breath (let alone sentence), but they’re two of the prominent figures on cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras’s new album of music for cello and orchestra. Elgar’s Cello Concerto, the disc’s opening work, receives a grand performance: weighty, tragic, and noble, one that calls to mind the incomparable Jacqueline du Pré, even if it doesn’t quite top the charisma with which she sometimes imbued the piece. Still, it’s a satisfying performance that captures the nostalgic, bittersweet quality of Elgar’s late worldview.

As a rule, Tchaikovsky’s works for solo instrument and orchestra tend to be pretty shallow vessels: the piano and violin concertos are brilliantly showy, but there’s not much beneath the virtuosic veneer. The Variations on a Rococo Theme are the closest Tchaikovsky came to writing a cello concerto and it’s filled with trademark tunes and show-stopping flashiness. Queyras handles everything with aplomb, though he can’t quite redeem the slightness of the material. Even so, the slow third variation passes like a dream and the finale is full of pep.

Much more impressive are the two short pieces by Dvorak that act as filler between the Elgar and Tchaikovsky selections. The first, a Rondo in G minor, is filled with classic, Dvorak-ian melancholy: phrases and melodic gestures foreshadow that composer’s Cello Concerto, but there’s a questing, pensive air to everything – it’s the kind of striking miniature that Dvorak could do so well.

The other work, Klid (or Silent Woods), is a beautifully essay for cello and a subdued orchestra of strings and winds. It’s not a showy piece – most of it takes place within the cello’s middle range – but achieves a straightforward expressivity that is at once heartfelt and memorable.

Jiri Belohlavek and the BBC Symphony Orchestra make fine accompanists: Queyras is always front and center, but the exchanges between soloist and orchestra (especially in the Elgar) are boldly realized – there’s a real sense of collaboration between all parties throughout.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: BBC Symphony Orchestra, Freiburger Barockorchester, Harmonia Mundi, Jean-Guihen Queyras, Jiri Belohlavek