Book Review: “Scissors” — A Sharp Exploration of the Creative Process

Scissors is a roman à clef. But Stéphane Michaka has not composed a fictionalized biography mapping out the itinerary of Raymond Carver’s life. The novelist above all focuses on the creative process in which a writer named “Raymond” is involved.

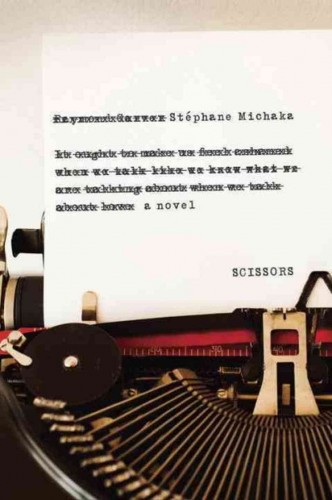

Scissors by Stéphane Michaka. Translated by John Cullen. Doubleday (Nan A. Talese), 209 pp., $25.95.

By John Taylor.

Admirers of Raymond Carver and even readers who have never opened a collection by the American short-story writer (1938–1988) will find themselves absorbed in Scissors, an astutely constructed novel written by the French writer Stéphane Michaka (b. 1974). The French original, Ciseaux, was rightly praised in France last year when it was published by Fayard. The story is gripping, almost surprisingly so, and the psychological, ethical, and aesthetic issues it raises are essential ones.

Given a lively translation by John Cullen, this fictional narrative is indeed closely inspired by Carver’s life and his relationships with his first wife Maryann Burk Carver (called “Marianne” in the novel), his second wife the poet Tess Gallagher (called “Joanne”), and his editor Gordon Lish (called “Douglas”).

It is thus a roman à clef. But Michaka has not composed a fictionalized biography mapping out the itinerary of Carver’s life. The novelist above all focuses on the creative process in which a writer named “Raymond” is involved: his drawing on intimate experience for his writing, his difficulties (notably stemming from poverty and alcoholism) to find the time and energy to write, his ambition to publish, and, once his work has been discovered by a domineering, New York editor — nicknamed “Scissors” — his inner turmoil about the aggressive cuts that are made in his manuscripts. Yet it is Douglas’s severe editing that enables Raymond to appear in print in one of the most important American magazines, to publish his first collection, and, soon thereafter, to become famous.

The novel opens with Raymond self-confined to a detoxification center after he has broken a bottle over Marianne’s head. We first hear him speaking as the initial narrator, and then Douglas — with whom Raymond has not yet interacted — takes the floor and begins revealing his own personality:

My imagination is concise. My work is reduction. I edit short stories, epics in miniature. [. . .] I’m not God. Who said I thought I was God? I have enemies everywhere in the publishing business. In rival houses, at other magazines. Enemies spreading like a case of psoriasis I purposely encourage. I love the constant eruption of envy around me.

After another passage in which Raymond confesses, to the co-director of the detoxification center, that he wants “to preserve at all costs” his stories if he can recover from his alcoholism (and in the process, he neglects to mention Marianne and their two children), Michaka inserts the short-story submission that first attracts Douglas’s editorial attention. Michaka has himself written this piece — “Who Needs Air?” — and the other stories that are used in Scissors; they are not Carver’s, though apt, moving imitations in their graphic realism and emphasis on telltale gestures.

Michaka thereby weaves Raymond’s, Douglas’s, Marianne’s, and later Joanne’s voice into a polyphonic tapestry that also includes full-fledged — “unedited” — stories at key spots in the narrative. Although this subject matter might seem exceedingly literary, the plot emerging from it is by no means stuffy. At stake here are not only the battle to write and be published but also, and especially, self-destruction, family responsibility, power over others, personal integrity, love, and the end of love. With its multiple viewpoints, vivid scenes, and strong emotional undercurrents, the tale of Raymond’s personal and literary struggles is thoroughly compelling.

The reader is a silent eyewitness who remains somehow particularly close to the action as it is conveyed through the characters’ spoken words. We watch Raymond slightly fictionalizing raw experience, usually changing little more than the names. Often this same raw experience is subsequently referred to by the other protagonists involved in it, especially by Marianne, who is thus a character in the novel but also a “fictional” (yet perfectly true-to-life) character in Raymond’s stories (within the novel). This fascinating Russian-doll effect also of course applies to Raymond (when he is an author within an author, as it were) as well as, similarly, to Douglas, who interacts with Raymond in real life and also “reworks” the autobiographical narrators of Raymond’s stories.

“Reworks” is a euphemism. Douglas heavy-handedly cuts away what he deems superfluous in Raymond’s writing. He sometimes eliminates whole passages, even several pages in a row. He changes the original titles as well. For him, Raymond has “too much heart.” Douglas in this novel, like Gordon Lish in American literary history, launches “minimalism”; only the barest narrative bones are allowed to remain in the final version of stories. But amid scenes in which Douglas self-confidently crosses out words, sentences, paragraphs, and pages, cracks show in the editor’s hard psychic surface. Douglas is not without moments of self-awareness. For example, as he muses about Raymond, he avows to himself this:

When I’m editing Raymond, a strange phenomenon occurs: I see Douglas through him. All his secrets are mine. When I edit Raymond, I have no more doubt.

Ruminating once again about his massive editing of Raymond’s stories, Douglas thinks aloud, almost touchingly:

His life, the giant screw-up he’s made of it—the two kids by the age of twenty, the debts, the booze, the wife who loves him and weighs him down, the domestic drama of the working-class guy who stubbornly keeps on writing—that’s what I was looking for. The chronicle of an absurd ambition. Prometheus chained to the corner mini-mart. [. . .] I feel empathy. My scissors aren’t for cutting so deep that what’s left is unrecognizable. Their work is to make the resemblance total. I look in the mirror, and who is it I see? Him or me?

The aforementioned notion of “heart” and its corollary, “hope” — whether a writer can have “too much heart” and whether he should, if he feels so inclined, offer glimmers of “hope” even in the grimmest personal or social context — is the pivot around which Michaka’s novel revolves. After Douglas has accepted for his magazine Raymond’s story “Petunias,” in the process changing the title to “Compost” and making massive cuts, Raymond reflects:

It’s the tale of a guy who wants to be forgiven.

That’s my subject. I’m not going to call it “Compost.”

The story’s full of hope. Like everything I write. Hope isn’t to be found on every page, but you do find the possibility that . . . in the course of the . . . when you get to the end . . .

Happy endings are out of fashion, but hope remains. It’s the hardest thing to grasp.

Further on in their increasingly antagonistic writer-editor relationship, Raymond begins to resist Douglas’s editing more and more. He pens a letter to him:

I don’t want my stories to be published in their present form. [. . .] Put simply, they’re no longer my stories. I recognize something very dark in them that resembles my past life, but I don’t see myself in them as I am today. I’ve come through all that. I sure came close to not making it, but if there’s one thing this collection—in my version—shows, it’s that I’ve come through. I didn’t write twenty-two short stories as hard-edged as despair. I don’t know where that despair comes from, Douglas. Is it yours?”

The dilemma that Raymond expresses so poignantly here recalls the aesthetic issue already formulated by Thomas Mann in his novella Tonio Kröger (1902). Speaking through the voice of his main character, Mann ponders the role of feeling for the writer:

. . . only amateurs think that a creative artist can afford to have feelings. It’s a naïve, amateur illusion; any genuine, honest artist will smile at it. Sadly, perhaps, but he will smile. Because, of course, what one says must never be one’s main concern. It must merely be the raw material, quite indifferent in itself, out of which the work of art is made, and the act of making must be a game, aloof and detached, performed in tranquility. If you attach too much importance to what you have to say, if it means too much to you emotionally, then you may be certain that your work will be a complete fiasco. You will become solemn, you will become sentimental, you will produce something clumsy, ponderous, pompous, ungainly, unironical, insipid, dreary, and commonplace; it will be of no interest to anyone, and you yourself will end up disillusioned and miserable. . . For that is how it is, Lisaveta: emotion, warm heartfelt emotion, is invariably commonplace and unserviceable. . . All emotion, all strong emotion, lacks taste. As soon as an artist becomes human and begins to feel, he is finished as an artist.

As to the French literary context in which the bilingual Michaka (who is well-versed in Anglo-American literature) is writing, André Gide’s proverbial quip also pertains: “It is with good feelings that one produces bad literature.” Every well-read Frenchman and Frenchwoman can recite this phrase as a sort of maxim: “C’est avec les beaux sentiments qu’on fait de la mauvaise littérature.”

Author Stéphane Michaka — he has written a novel in which the boundaries between good and bad, right and wrong, hope and despair, fiction and reality remain appropriately — realistically — fuzzy.

When Gide notes this down in his Journal on September 2, 1940, he is not implying, inversely, that “bad feelings” constitute a sufficient condition for producing “good literature”; he is pointing out, like Mann in Tonio Kröger, that there is a danger inherent in noble sentiment when it comes to writing. As Gide explains in the same diary passage, “good intentions often make for the worst art and (. . .) the artist runs the risk of damaging his art by wanting it to be edifying.” Gide goes on to mention a well-known poem that he personally finds mediocre — Charles Péguy’s “Eve” — and posits that the many readers admiring it “remove themselves from the realm of art and place themselves in a completely different vantage point.”

If one uses Gide’s aphorism as a criterion, Douglas, as an editor, is on Gide’s and Mann’s side. All the while claiming to improve the artistic qualities of Raymond’s narratives, Douglas pares away all signs of what he considers to be “edifying” hope so that only the gritty, even sometimes sordid, details of the plots remain, along with endings that leave no room for the slightest optimism.

Scissors thus chronicles, from four viewpoints, a growing conflict with psychological, ethical, and aesthetic ramifications. Rising in opposition to Douglas’s systematic stylistic bias is the original impetus behind Raymond’s writing, not to mention his retrospective vantage point once he has stopped drinking for good and seeks to acquire control over the future development of his literary career — which, like Carver’s, will be nipped in the bud by lung cancer soon thereafter, at the age of 50. By increasingly standing up to the very editor who has forged him and given him a livelihood (for Raymond now can supplement his royalties by teaching creative writing), the short-story writer becomes ever more aware of what he had been trying to accomplish, via writing, from the onset. As Raymond puts it above, his stories are about a “guy” (himself) who seeks to be forgiven. By writing, he has sought to save himself, but not in the manner that Douglas has designed.

Seeking forgiveness can surely be expressed in countless edifying ways in prose. Any writer doing so falls prey to the artistic traps that Mann and Gide pinpoint. But this is untrue of Raymond’s stories in their original drafts (as credibly invented by Michaka). Toward the end of the novel, Raymond decides to drop Douglas as his editor, and, in an intense encounter inside the latter’s New York office, he declares, “I don’t want you cutting me anymore. [. . .] I am anything but a minimalist.”

Readers of Raymond Carver know of the battles that Tess Gallagher waged to recover and publish her husband’s original drafts. Michaka stages an analogous meeting, after Raymond’s death, when Joanne announces her intentions to Douglas. In Joanne’s version,

I remain silent.

“A terrible responsibility, Joanne.”

He feels my resolution wavering.

I gather my strength. “I know what I am doing.”

“In that case—“

He opens the door.

“But don’t say ‘butchery.’ Don’t say I butchered his stories.”

At the instant when the door shuts, I think I hear him say, “I loved him too much to do that to him.”

But the wind chimes drown out his words.

There are many such fine touches in this book. Michaka constantly deepens the psychological intricacy and ambivalence of his characters as well as their interactions with one another. Note that although Raymond is the main character, Douglas’s nickname “Scissors” — which also refers to his editing, of course — is used as the title of the book. The author knows that Douglas is also fragile in his own secret ways. Although the two heroines, Marianne and Joanne, are, arguably, somewhat less complex than the two men, their roles are no less engaging. Ultimately, this thought-provoking novel avoids the pitfalls designated by Mann and Gide in that boundaries between good and bad, right and wrong, hope and despair, fiction and reality remain appropriately — realistically — fuzzy.

John Taylor is the author of the three-volume essay collection Paths to Contemporary French Literature (2004, 2007, 2011). He has recently translated works by Philippe Jaccottet, Pierre-Albert Jourdan, Louis Calaferte, and Jacques Dupin. His most recent collection of short prose is If Night is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press, 2012). Originally from Des Moines, he has lived in France since 1977.

Tagged: fiction, Gordon Lish, minimalism, Raymond Carver, Scissors

A thoughtful, absorbing review of a novel based on one of the great puzzles in American literature — the fraught relationship between the Carver camp and Carver’s editor, Gordon Lish. Taylor made me want to read more about a subject I thought I was done with.