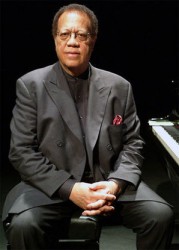

Fuse News: Grace Notes for Pianist Cedar Walton

By Michael Ullman.

For a time, particularly during the early sixties, pianist Cedar Walton seemed almost ubiquitous. In the course of his long and respected career Walton would take part in over 400 recording sessions. From 1955 (when he left the army and moved to New York City) until his death on August 19 at the age of 79, the pianist was a vital member of some of the most potent bands in jazz history, most famously Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, with whom he played and for whom he recorded between 1961 and 1964.

Blakey’s music was dubbed ‘hard bop,’ yet there was little that one would call hard about Walton’s playing, though his performances could be intense. Walton’s fingers seemed to dance across the ivories, particularly when he was performing his own nimble compositions. He could be funky, as on his pieces “Jake’s Milkshake” (found on Spectrum, Prestige) and “Shaky Jake” (on Blakey’s Buhaina’s Delight, Blue Note). Yet his playing even in the latter tunes always had a lyrical lilt. Walton composed dozens of blues, one of his most memorable, “Bremond’s Blues,” he recorded solo (Cedar Walton at Maybeck, Concord) and in a trio (Ironclad: Live at Yoshi’s, Monarch). Yet there’s not a blues cliché amongst them: his playing, while recognizably bebop, proffers an agile gracefulness that made him unique amongst his talented generation of pianists.

Walton’s mother was his first teacher: he continued his studies at the University of Denver, where he is reputed to have played with dozens of travelling musicians, including John Coltrane. He moved to New York City to jump start his career, but was soon drafted. He made the most of his army experience, meeting and playing with other musical soldiers, such as saxophonist Leo Wright. Back in New York City, Walton was immediately in demand, not least because he was a fast reader, a brilliant composer and arranger, and seemingly able to fit in anywhere. His first recording was on trumpeter Kenny Dorham’s This is the Moment on July 7, 1958. In the next six years, he would join and record with most of the young masters of the bebop era. He was on Dorham’s Blue Spring, trombonist J. J. Johnson’s J.J., Inc, Wayne Shorter’s Second Genesis, Freddie Hubbard’s Body and Soul and Hub Cap, and Lee Morgan’s The Rajah, as well as sessions with Jimmy Heath, Joe Henderson, Eddie Harris, Lee Morgan, Art Farmer, Clifford Jordan, Curtis Fuller, and Blue Mitchell. He was the pianist for Benny Golson and Art Farmer’s famous Jazztet, and when Walton was with Blakey he made a half dozen of the Jazz Messengers’ most celebrated recordings, including Ugetsu, for which he wrote the title tune.

He was thrown for a loss only once. In March 1959, Walton was hired to record several new compositions with John Coltrane, including Coltrane’s “Giant Steps,” a now familiar tune in which the sax player deliberately lets a series of chords awkwardly fall downward, the sound suggesting what he perceived to be giant steps. The Walton session has now been reissued, and we can hear Coltrane urge the band not merely to make the changes but “to tell a story.” Walton never got a chance: he didn’t solo. Weeks later, Coltrane remade the tune with pianist Tommy Flanagan.

Walton always wrote and he became a stellar, though often overlooked, composer of jazz tunes when he was with Art Blakey. He was unlucky in terms of his timing. In the Blakey band he was overshadowed by saxophonist Wayne Shorter, whose inevitably intriguing compositions attracted more attention than Walton’s efforts. That started to change when Walton began recording on his own in the late 60s. Nine of his compositions can be found on Cedar Walton Plays Cedar Walton, including the delightful “Short Stuff,” an instantly ingratiating tune played to perfection by a tightly muted Kenny Dorham. The disc is an excellent place to begin a Cedar Walton collection: it includes the funky “Higgins Holler” with Walton’s chattily comping behind the horns as well as a strong version of Walton’s hit “Ugetsu,” first recorded with Art Blakey.

Given such a prolific career, Walton played everywhere. As far as I know, his last appearance in Boston was when, still musical but with clearly diminished technical skills, he played at Tufts on February 25, 2011. Luckily Walton’s recording legacy is rich and varied: one can hear him play solo, in duet with bassist Ron Carter on Heart and Soul (Timeless), with his trio (Walton particularly liked Ironclad: Live at Yoshi’s, Monarch), and with the small, hard bop groups, including Eastern Rebellion, a band that Walton made distinctive with his spot-on grace and sweetly original blues feeling.

Born and raised in Belmont, MA, Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet, and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, the New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, the Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling and others have appeared in academic journals. For over twenty years he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University He teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.