Classical CD Review: An Inspiring 80th Birthday Tribute to Conductor Claudio Abbado

This attractive, inexpensive box set dedicated to Claudio Abbado contains a rich gathering of lucid, colorful recordings, among the most accomplished modern performances of symphonies that are absolutely central to the repertoire.

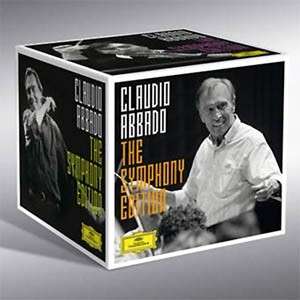

Claudio Abbado Symphony Edition: Symphonies of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Franz Joseph Haydn, Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Schubert, Frederic Mendelssohn, Johannes Brahms, Anton Bruckner, Gustav Mahler. Orchestras including Orchestra Mozart, Chamber Orchestra of Europe, London Symphony Orchestra, Lucerne Festival Orchestra, Wiener Philharmoniker, Berliner Philharmoniker, Mahler Chamber Orchestra. (2013) – 41 disc Box set, Deutsche Grammophon, $94.19.

By Michael Ullman

This imposing set, recorded mostly between 1986 and 2012 (the exception is the 1967 Brahms Serenade No.2) celebrates the 80th birthday of the supremely accomplished conductor Claudio Abbado, who was born in Milan on June 26, 1933 and who made his debut in the same city in 1960. It contains distinguished recordings of the complete symphonies of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Brahms, Schubert, and Mahler, five of Bruckner’s, six Mozart symphonies (including the last three), eight of Haydn’s (including the Drum Roll), plus overtures, serenades, and incidental works by Brahms, Mendelssohn, and Schubert.

Listening to this gathering of recordings leave one in awe of the conductor’s range and productiveness: yet this set doesn’t touch on the over 20 complete operas he has recorded. Who has recorded more sparkling versions of Rossini’s La Cenerentola or Il Barbiere di Silviglia? Nor does it take notice of his investigations of more contemporary music, including his distinguished recordings of Bartok.

Instead of the definitive Abbado collection, we have a rich gathering of lucid, colorful, detailed recordings, among the most accomplished modern performances of symphonies that are absolutely central to the repertoire, and packaged in an attractive, inexpensive box. In Abbado, who has been the musical director of La Scala, the Vienna Philharmonic, and the principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic (replacing Herbert von Karajan), we have (to my ears) the ideal conductor. (Bostonians have heard him conduct the BSO performing Ravel and other composers.) Abbado seems to capture not merely the style but the unique sound and personality of every composer he approaches: he renders with equal skill the terse wit of Haydn, the long-lined (and, to me, long-winded) phrases of Bruckner, the depths of Beethoven, and the sardonic romanticism of Mahler. All are reproduced in beautifully balanced performances filled to the brim with illuminating details.

There are surprises: the brisk pace and impressive precision of the finale of Mozart’s Symphony, the clarity and occasional prominence of the percussion and winds, may remind many of so-called “historically informed” original instrument performances. I imagine some listeners will find the tempo too fast, a reminder that one of Abbado’s early influences was Toscanini. Happily, Abbado heard Toscanini rehearse and was shocked by the way the older man harangued the members of the orchestra. Abbado vowed never to be such a nasty martinet. His own rehearsals are described as consistently calm.

In the notes to this collection, the conductor explains one aspect of his approach: “I often get the various orchestral groups to play on their own. But I don’t do so in order to expose their mistakes or beause they need correcting but for the benefit of others: It is so that the rest of the players can hear what their colleagues are playing at this particular point in the score. Rehearsals can be tedious. Of course, I try to ensure that individual passages turn out in the way that I’ve learnt they should from the score. But then, at the concert, you get this sense of the overarching structure, the flow of the whole, the actual form of the piece. That’s what’s most important.” Perhaps that is the reason so many of the recordings included here, including all the Mahler and Beethoven, are live recordings.

It is hard to say what is most impressive about an Abbado performance. When I saw him conduct Beethoven with the Vienna Philharmonic, it was at first the beautiful sound he evoked and then his mastery of what Abbado calls most the important virtue of all, an appreciation of the overarching structure of the piece. His manner of reproducing that structure has what the superb critic B. H. Haggin called “plastic continuity,” the art of making even a lengthy and complex composition hold together rhythmically, of generating a seamless whole out of a series of fragments.

What further distinguishes Abbado is his ability to create incandescent performances from an ambitious range of pieces. Leonard Bernstein also conducted Haydn (the Paris Symphonies) brilliantly, but when he got to Mahler, for which he is still acclaimed, Bernstein frequently sacrificed continuity for the sake of local effects. (He also made anguished faces while conducting to stress Mahler’s supposed neuroticism.) Abbado’s way with Mahler is one that accents ease: I don’t know an opening of Mahler’s First that creates more of a sense of expectation than Abbado’s, or that fulfills those expectations so gracefully. This is not to say that Abbado’s Mahler is not dramatic, listen to his opening of the Second Symphony, perhaps his finest rendition of a Mahler symphony. This recording, with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra (the only Mahler here not performed by the Berlin Philharmonic) is Abbado’s third recording of the piece. Again, the lovely sound, the careful balance of the parts, entrance. Abbado is wonderfully patient with Mahler: every climax is prepared. He doesn’t whip up the orchestra, so it never sounds unduly frenzied. Another way of putting it is that he manages to convey the continuities as well as the stormy contrasts and sardonic surprises in Mahler’s symphonic compositions.

There are of course no such sardonic surprises in Schubert or Mendelssohn, but the only modern versions of Schubert’s 3rd and 5th symphonies that I prefer to Abbado’s were conducted by Colin Davis, and I may be influenced by the natural glow of having heard the latter conduct them live. In this set, one also gets the joy of hearing Abbado’s elegant conducting of Brahms’ Variations on a Theme by Joseph Haydn, as well as all four Brahms symphonies. His Beethoven has similar virtues. But I could go on almost indefinitely. Here are sublime performances of many of the symphonic masterpieces that make up the classical canon. That they come in such an inexpensive package is an added enticement.

Tagged: Claudio Abbado, Claudio Abbado Symphony Edition, Deutsche Grammophon