Book Review: ‘Chuck Close: Life’ ignores the Big Questions

The narrative turns out to have the blandly cheerful tone and slightly stilted prose of an official biography: the sort of thing with the CEO’s picture on the cover, given out at stockholders meetings.

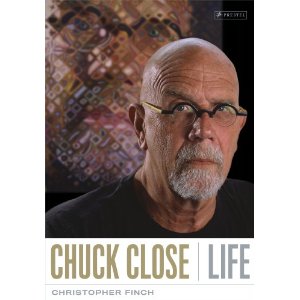

Chuck Close: Life, by Christopher Finch. Prestel, 352 pages, $34.95.

Chuck Close: Life, by Christopher Finch. Prestel, 352 pages, $34.95.

Reviewed by Peter Walsh

In these media-saturated, image-obsessed times, every public figure is surrounded by a cloud of buzz. Inside, like so many motes of dusk, float supporters and detractors, mentors and hangers on, friends and rivals, family and lovers, the grateful and the betrayed, news stories, documents, secrets, hype, rumor, lies, and hints at the truth.

When the time comes, if it does come, for a serious biography, the writer’s first job is to filter through all this: to make judgments about what really matters, ignore the fluff, and put everything in some kind of order.

This, unfortunately, is not what happens in Chuck Close: Life. Author Christopher Finch is a painter, a prolific art writer, and former curator at the Walker Art Center. His previous books, among them an early study of Pop Art, a biography of Judy Garland, and a companion monograph, Chuck Close: Work, range from serious to frankly commercial. Chuck Close: Life falls somewhere, awkwardly, in between.

Finch has been a devoted friend of his subject matter for some 40 years. The book, Finch explains in his preface, was not only the artist’s own idea but “the result of a huge act of generosity on the part of Chuck Close.” Finch’s account does, in fact, rely very heavily on interviews with his subject, his family, and an inner circle of long-time friends and admirers.

Finch seems to have little impulse to fact-check or even take a second, skeptical look at his voluminous but entirely subjective sources. Chuck Close: Life has just 24 footnotes, taking up a page and a half of a 350-page volume. It has no bibliography at all. A well-researched biography or work of non-fiction typically has hundreds of entries in both, together covering as much as a third of the whole.

Can such a book, in any way, be objective? For sure, there seems little in it that might ripple its subject’s own self-image.

It’s not entirely surprising, then, when Finch’s narrative turns out to have the blandly cheerful tone and slightly stilted prose of an official biography: the sort of thing with the CEO’s picture on the cover, given out at stockholders meetings or that appears in bookstores a few months before a presidential primary.

You know the plot already. The start is humble, but family, friends, and teachers all recall early signs of brilliant talent, great promise, and true generosity; detractors have hidden agendas; challenges are overcome; tragedy hurts deeply but strengthens. There are some years of struggle but success, when it comes, is triumphant and richly deserved.

Such books are intended to polish an image, not illuminate a life. Most are quickly forgotten.

Close deserves better. He is an important artist with an interesting and possibly instructive life. Born to a modestly middle class family in Monroe, Washington, Close is one of those American originals to come from extremely ordinary backgrounds in out of the way places (think Rauschenberg in Port Arthur, Texas; Hartley in Lewiston, Maine; Pollock in the scrappy small-towns of the American West; Warhol in working-class Pittsburgh), who nevertheless went on to set American art on a daring new path.

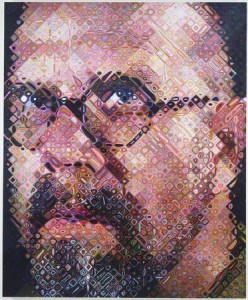

Coming as Pop Art and ‘60s counter culture both seemed to sputter to a halt, Close’s gigantic portraits, vivid and photographic yet clearly meticulously handmade, made an indelible impression.

Yet, in Finch’s book, all this disappears behind a barrage of anecdotes and shop talk. The stories of youthful antics and eccentricities are charming at first. But after a hundred pages or so, you feel you are trapped in a hotel bar after a funeral or a testimonial dinner with a couple dozen half-drunk guys laughing over old tales about some poor sod you don’t even know.

Artist biographies are tough. You have a life, a career, and a body of work. The three must somehow be related, but you can never mix them up. A great artist can have a miserable life and a messed-up career. On the other hand, a brilliant, successful career and an exciting, rewarding life can leave nothing behind but wasted canvas.

Self Portrait, Chuck Close

Case in point: Finch’s decision to pivot the book on Close’s sudden illness in 1988, a near-death experience that left him mostly paralyzed. The plot device, as Finch uses it, combines a dramatic personal tragedy with an inspirational story of inner strength overcoming physical adversity.

Finch may have been deliberately echoing Franklin D. Roosevelt’s famous bout with polio in 1921, which robbed him of the use of his lower body. The struggles Roosevelt endured as a paraplegic, his biographers claim, helped transform a pleasant, if over-privileged and somewhat spoiled amateur politician into a great and empathetic president.

By 1988, though, Close had been a prominent artist for 20 years. His most iconic work already hung on the walls of museums. So his paralysis was a great personal tragedy and yet not a disaster for his work. Or even, in Finch’s account, more than a temporary interruption of his career. The illness tested the man. But it didn’t make the artist.

Finch’s book is hardly a waste. It is mostly an easy, jargon-free read. The author’s long-standing personal relationship with the artist means that there are some intimate and revealing glimpses of the artist at work. There is much here to interest and entertain even a casual interest in late 20th century American art.

If Close’s work lasts (and I think it will), there will be plenty in Chuck Close: Life for future biographers to mull over. Still, Finch leaves the Big Questions about this particular life to them.

================================

Peter Walsh studied art, design, and art history at Oberlin College and Harvard University. A former Director of Publications for the Harvard University Art Museums, he has served on the staff of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Harvard Museums of Natural History, and the Davis Museum and Cultural Center at Wellesley College and has been a consultant to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, and the Art Museum Image Consortium, among many other organizations. He contributed to scholarly books on museum studies and new media, has lectured widely in the United States and Europe, and has published over two hundred articles and reviews in The Arts Fuse and elsewhere.

Tagged: artist, Christopher Finch, Chuck Close, Prestel

I was just looking at a note about this book last night and was considering purchasing it. Thank you for so honest a review.

Close is coming to D.C. later this month for a talk at the Corcoran, in conjunction with his show there.