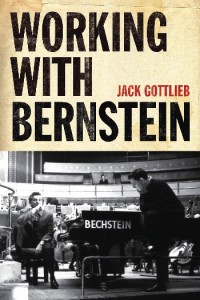

Book Review: Working with Bernstein

Working with Bernstein: A Memoir by Jack Gottlieb. Amadeus Press, 370 pages, $24.99.

Working with Bernstein: A Memoir by Jack Gottlieb. Amadeus Press, 370 pages, $24.99.

Reviewed by Caldwell Titcomb

A strong case can be made that the late Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) was the all-round greatest musician our country has produced—virtuoso pianist, composer of both classical and popular music, the most charismatic conductor of his century, acclaimed educator and lecturer, author, and public intellectual.

It is also probable that his career is the most fully documented in musical history. He has been the subject of numerous biographies. The print media have gone to town over the years (including the cover of Time magazine). Television cameras have amassed a huge body of visual coverage. His recordings total more than those of anyone else in the world. His countless attendances and speeches at leftish political events caused the Federal Bureau of Investigation to compile a dossier on him that ran to at least 666 pages.

You might think that there is nothing fresh to be said about him, but you would be wrong.

There has just appeared an important book entitled Working with Bernstein: A Memoir, which is crammed full of information unavailable anywhere else. It is written by Jack Gottlieb, who is a prolific composer himself. Gottlieb enrolled in a graduate course taught by Bernstein in 1954. Bernstein then hired him as an assistant to undertake all manner of tasks, extending from 1958 to 1970. After several years as music director of a temple in St. Louis, Gottlieb returned to New York and resumed his employment by Bernstein for the rest of the latter’s life, and since then has been the senior member on the staff of what is now called the Leonard Bernstein Office.

Gottlieb divides his book into two main parts. The first he calls “A Grab Bag of My Life With LB,” which contains “reminiscences, anecdotes, observations, testimonies, little known facts.” He keeps track of the frequent change of New York apartments along with the business staff (notably Helen Coates, Bernstein’s one-time piano teacher who became his secretary). “On the Road” describes Bernstein as “a notoriously reckless driver,” and provides an account of the awful time that everyone, including movie star Bette Davis, tried to cope with a Washington snowstorm at the time of the inaugural gala for President Kennedy.

Gottlieb was advised to keep a diary during foreign tours with the New York Philharmonic and the Israel Philharmonic, so he was able to supply detailed entries about the places visited in an “On Tour” section. “In the Workroom” is especially informative about recycling: “Bernstein was never one to let a good tune go to waste.” Gottlieb lists a host of musical ideas that began in one place and ended in another—something that nobody else could have supplied. Discussed too are Bernstein’s jottings in his orchestral scores, and his special commitment to Gustav Mahler. Bernstein did more than anyone else to implant Mahler’s music firmly in the core repertory (he recorded the cycle of all nine Mahler symphonies three times, although he unfortunately refused to perform Deryck Cooke’s wonderful completion of the nearly finished Tenth).

Author and composer Jack Gottlieb

In “Keeping Faith,” Gottlieb devotes a substantial number of pages to the Jewish content in Bernstein’s output, including Mass, an ostensibly Catholic (and still controversial) work written for the 1971 opening of the Kennedy Center in Washington. “Spinning Platters” deals with Bernstein’s discography. Gottlieb says that not even Herbert von Karajan or Sir Neville Marriner comes close to Bernstein’s total of 826 recordings. Asked once to name his own favorite recordings, he gives us his Top Ten lists for Bernstein as a conductor and for Bernstein as a composer.

“Teaching and Television” gives us an account of the Bernstein course that Gottlieb took, the televised Omnibus programs (from 1955) directed at adults, and then, especially, the 53 televised Young People’s Concerts that Bernstein—as explicator, pianist, and conductor—presented with the New York Philharmonic from 1958 to 1972. (In 1992 Gottlieb edited a volume of 15 of these scripts with musical examples and appended a list of all 53 programs and the music performed in each.) Gottlieb ends Part One with a moving account of Bernstein’s last days and funeral.

Part Two is devoted to Bernstein’s compositions—what Gottlieb calls “My Notes on LB’s Notes.” Gottlieb knows Bernstein’s oeuvre more intimately than anyone else alive. And this half of the book is a godsend since it pulls together conveniently in one place a host of Gottlieb’s writings scattered here and there among concert programs, record jackets, essays, and forewords to scores.

Gottlieb provides many musical examples as he proceeds through the compositions by genre: chamber music, choral works, dance and theater works, Jewish works, commentaries, overtures and entertainments, and songs. My one tiny complaint concerns the failed 1972 musical 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue (only seven performances, one of which I attended), which centered on our country’s presidents and first ladies along with their black servants. Gottlieb names the pair of actors who played the “upstairs” personages (Ken Howard and Patricia Routledge), but he failed to name the equally important black “downstairs” performers (Gilbert Price and Emily Yancy)—an unfortunate omission since the late Price (1942-91) was as great a baritone as we’ve ever had and garnered three Tony nominations during his career. (Incidentally, Price triumphed in the central role of the Celebrant in a California production of Bernstein’s Mass.)

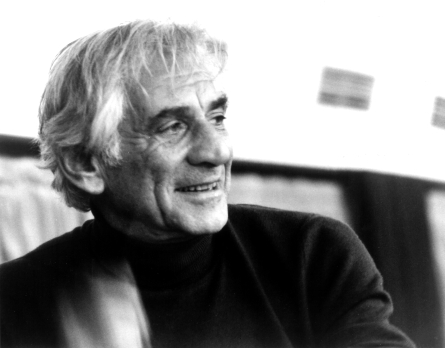

Leonard Bernstein: One of the most remarkable titans in musical history.

I spotted only a handful of errors in the book. Gottlieb began his graduate studies in 1953, not 1954 (p. 20). Bernstein’s tenure as music director of the New York Philharmonic is stated to have ended in 1966 (p. 24) and 1968 (p. 327), when it actually lasted through the spring of 1969. There is a reference to Justice Learned Hand of the Supreme Court (p. 40); although many wish he had served there, he actually sat on the U. S. Court of Appeals, Second Circuit, from 1924 to 1961. Bernstein studied orchestration at Harvard not with Edward Burlingame III (p. 328 and 349) but with Edward Burlingame Hill.

Gottlieb does not delve into Bernstein’s unswervingly liberal political activities. For this, one can turn to the recent book Leonard Bernstein: The Political Life of an American Musician by Barry Seldes (University of California Press, 2009). Seldes spends a lot of time on Bernstein as a “man who brooded over what he considered his failure to compose a masterwork of lasting importance.” While Bernstein may, in Seldes’s view, not have found a subject that spurred him to write a great classical opera, there are other ways to achieve “lasting importance.”

Gottlieb considers the ballet Dybbuk to be Bernstein’s “shining masterpiece,” displaying “the skill and imagination of a composer at the peak of his powers” (pp. 162, 241). As for me, I would posit at least the following as masterly achievements: the ballet Facsimile, “The Age of Anxiety” (Symphony No. 2), the violin “Serenade,” the operetta Candide, the musical West Side Story, and the choral Chichester Psalms. In addition, I consider his music for the movie On the Waterfront (1954) one of the two greatest film scores ever written—the other being Sergei Prokofieff’s score for Alexander Nevsky (1938).

Gottlieb’s publisher is to be commended for allowing a total of more than 75 photographs to appear in this tome. They add enormously to a text that substantially increases what we have heretofore known about one of the most remarkable titans in musical history.

==========================================

Order Working with Bernstein through the link below to Amazon and The Arts Fuse receives a (small) percentage of the sale:

Tagged: American, conductor, Jack Gottlieb, Leonard Berstein, musical, Opera

Bravo Caldwell – once again ! —- Eliot