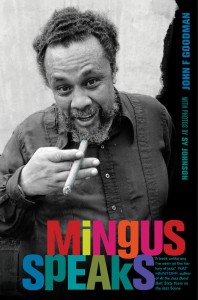

Book Review: Words From a Bedeviled Life — “Mingus Speaks”

The best parts of this book of interviews come when Charles Mingus or his collaborators talk about the music.

Mingus Speaks by John F. Goodman. U. of California Press, 350 pages, $34.95.

By Michael Ullman

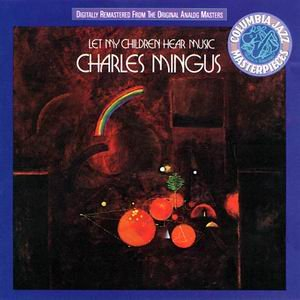

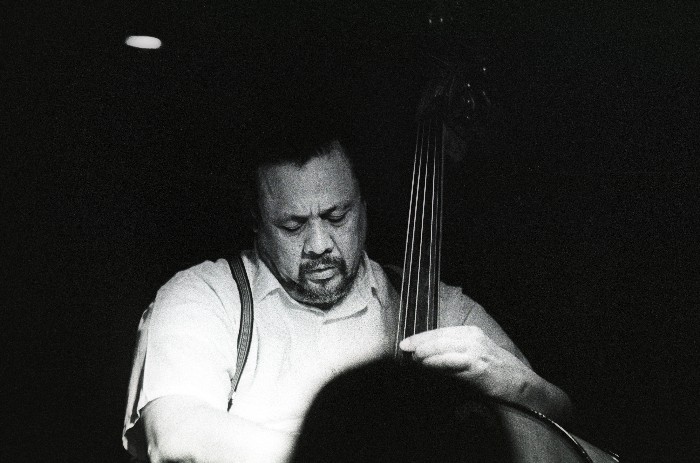

His last wife, Sue Mingus, said of bassist/composer Charles Mingus that he was the only man she had met who could talk for days at a time. In my experience, and in my one conversation with him, he spoke in rapid, barely comprehensible bursts that were very unlike his patiently paced bass solos. His occasional on-stage harangues were legendary. They weren’t always appreciated. When his masterful big band record Let My Children Hear Music was issued, I was told by a droll, hip record store clerk that the lp cost $3.95 with an essay by Mingus enclosed and $4.50 without.

Yet his was a capacious as well as an ornery mind, and he was often generous as well as principled. In the first interview by author and ex-Playboy critic John Goodman in Mingus Speaks, the new book of conversations he held with Mingus between 1972 and 1974, Mingus responds at length to a provocative and, it seems to me, insensitively phrased question. Goodman asks if “people most involved in this free jazz, like Archie Shepp” are “trying to con the white folks.” The alternative Goodman offers is that these musicians are conning themselves.

Mingus responds first by saying tactfully that he doesn’t know “about using their names,” and then goes on to talk broadly about the beautiful, structured music of Charlie Parker and of Bach. “Stravinsky is nice,” Mingus says, “but Bach is how buildings got taller.” Soon, he is remembering a time when he heard Ornette Coleman playing a piano and says that he didn’t cut it: “He sounded like a poor man’s Charlie Parker.” Much later, he compares Coleman and Dexter Gordon to the avant-garde player’s detriment. In a rather sycophantic manner, Goodman quickly chimes in about Gordon: “He’s a professional, man.” By implication, and we should remember that it’s Goodman not Mingus who says it, Coleman was unprofessional.

Mingus had real doubts about the avant-garde, but I also wonder if in these responses were influenced by the interviewer and his questions. In Brian Priestley’s biography of Mingus, the bassist is much more generous to Coleman: “Now aside from the fact that I doubt he can even play a C scale in tune, the fact remains that his notes and lines are so fresh. So when Symphony Sid played his record, it made everything else he was playing, even my own record that he played, sound terrible. I’m not saying everybody’s going to have to play like Coleman. But they’re going to have to stop playing Bird.”

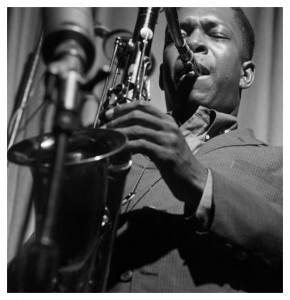

John Coltrane — He “was a very serious person and seriously in love with his music, a very religious man.”

In one of the most interestingly detailed statements about his own music in Mingus Speaks, Mingus talks about one piece, “The Shoes of the Fisherman’s Wife are Some Jiveass Slippers,” on the album Let My Children Hear Music: “I have two spots in there that definitely make fun of the avant-garde musicians. If you listen, you’ll hear McPherson and Hillyer playing Charlie Parker, and then at the end of the ‘Fisherman’s Wife,’ you hear Ornette Coleman, played by Teo Macero, and then playing all over, this beautiful alto sax, just like Bird, but McPherson’s tone cut everything they were doing. . . . the idea is that with all this going on, here’s this guy playing music and going to good notes behind or against this bass melody, and (McPherson) he’s playing pure honesty, not saying, ‘Look at me, I’m a king,’ or “I’m better than you.” Just doing his best he can, like Bird did through the changes, and it’s beautiful, man.” In the piece, it’s a significant moment, immensely touching because it suggests Mingus’s own struggle to be heard in all his pure honesty. But what he calls a parody of avant-garde music draws on the former’s techniques, and it provides the ending of the piece with an intriguing, different texture. Mingus heard something in that music that was useful to him.

Mingus’s intentions were always what he would call pure, which in his mind also meant inclusive, even inclusive of the avant-garde: “I’ve been waiting till the day when I get a chance to write classical, pure, serious music that came out of all the musics.” In one respect, his goal was to be like Charlie Parker, or perhaps Bach: “He (Parker) played beautiful music within those structured chords. He was a composer, man, that was a composer.”

Though Mingus was frequently out of work in the ’70s, and seemingly out of luck, he refused to compromise. He says in Mingus Speaks and in the Priestley volume that he knows how to please audiences, but he won’t do it. Nor did he like to be tied down to any one approach. We learned this early. In his notes to the 1960 recording Blues and Roots, he insists that the music on this recording was only one side of him. Music should be various. This is one of his principle objections to the avant-garde, which to his ears was monochromatic. “Take John Coltrane,” he tells John Goodman: “he went back to Indian-type pedal point music, but he got in a streak. Why couldn’t he do other things too? Why do guys have to stylize themselves? Don’t they know that in the summertime you wear thin clothes and straw hats and in the wintertime, you know, you got a right to play a different tune?”

Nor, with his love of complexity, especially harmonic complexity, was he interested in what he had heard of African music, or the music of those who asserted they were influenced by it. Goodman encourages Mingus to talk about this topic. The interviewer says, “I wanted to go back to the wailing and the African thing,” and Mingus responds simply, “You want to talk about John Coltrane.” It turns out that Goodman had written a piece about African music, and he tells us what the tradition is really about: “African music is really…tribal music.” After this revelation, which lumps all the music made in that vast continent together, Mingus tries to get off the subject: “I’m closer to America in a lot of ways than I am to Africa.” So was Coltrane, whom Goodman seems to want to undercut. Mingus won’t have it: “John was a very good man, very nice person, and the music he played told that. He was a very serious person and seriously in love with his music, a very religious man.” Coltrane’s Kulu Se Mama, one might add, is not weaker because it is not African.

Given Mingus’ reputation for cantankerousness, it is amusing to note that it is Goodman, not his subject, who calls the usually esteemed critic Ralph Gleason “a disaster.” Mingus was furious at John S. Wilson for an ambivalent review of his Philharmonic Hall concert, but it’s Goodman who says that Nat Hentoff’s wife was a better writer than her husband and who calls the admittedly intemperate writer Frank Kofsky a “hip white asshole.” To my mind, this is entrapment. But Goodman isn’t alone. In a joint interview with Mingus and his wife Sue, it is Sue who leads an attack on jazz promoter George Wein, saying that Wein made it impossible for Mingus to tour abroad. About this point, the musician is noncommittal. (Late in the book, Sue also calls Mingus out on his “screaming and yelling and punching,” while admitting that what she calls Mingus’ exaggeration, his extremes, were necessary to his achievement.)

Mingus’s objection to critics is that they could make it difficult for musicians to make a living. In an interview with producer Teo Macero in the book, Macero belabors the same point. Fact is, critics perennially make easy scapegoats for the difficult to impossible economic situation jazz musicians must deal with, a situation that Mingus laments regularly here and elsewhere. No wonder he’s disturbed: at least twice he ended up working for the post office. But his friends, including Max Gordon, owner of the Village Vanguard, and his arranger Sy Johnson, talk about the difficulties that Mingus created for himself by his occasional bursts of anger, impatience, or despair.

The best parts of this book of interviews (with substantial commentary by Goodman) come when Mingus or his collaborators talk about the music. Sy Johnson was the arranger/orchestrator for much of Let My Children Hear Music. Johnson talks memorably about Mingus’s use of such things as old pop tunes: “He just transforms material, a lot of material that’s around him. . . . he just takes in enormous amounts of music from every source he can. And it all gurgles around in there and is finally spewed out as something that is quite uniquely humorous.” Johnson says Mingus could orchestrate but so slowly it became impractical. Mingus was, interestingly, “not . . . egotistical about his music,” that he’s “willing to let it go.”

Yet when Mingus thought that his piece “Don’t Be Afraid, the Clown’s Afraid Too” needed an ending, he first asked Johnson to write one, which he did. When he heard Johnson’s ending, he said it sounded like rock and roll. Mingus then thought up an ending himself.

He was volatile and changeable, sometime to his collaborator’s despair: “With Mingus, the options are open, they’re open to change even after the piece is played, recorded.” When the record came out, there was some controversy about Mingus properly crediting Johnson, at least to the latter’s satisfaction. There’s some payback in this book. In the original interview transcribed in the ’70s, Johnson talks about helping Mingus with the composition, “Taurus in the Arena of Life.” In the notes to Mingus Speaks, Johnson comments, “I was doing my usual thing of minimizing my role so as not to spoil his image. Actually he only gave me a an eight-bar fragment that he said had some Tatum voicings he knew from working with him, and he wanted it used the way Duke [Ellington] uses Harry Carney in the band.”

Sue Mingus says in her blurb on the back of Mingus Speaks that the ’70s were a dark period in her husband’s life. In one of most interesting chapters, in which Mingus is encouraged to reminisce about his bebop heroes, he calls Bud Powell, Charlie Parker, and Fats Navarro “like saints to me.” As were most people, he sounds mystified by Bud Powell, but Mingus tells an interesting story about trumpeter Fats Navarro. When Mingus was with Lionel Hampton, Hampton invited Navarro on stage for a jam session. Mingus played an extended solo on “How High the Moon,” “fast as horns.” Navarro criticized him afterwards: “You didn’t say nothing, Mingus, you just played the theory. You didn’t tell me how you felt . . . You didn’t play nothing beautiful.” That, he said, woke him up. Those men, he said, had a religious thing, and, more poignantly, “they had a communication with a quiet life.”

I strongly suspect that Mingus never had a connection with a quiet life. At one point in this book, he opines that jazz is dead. Later, he says he is writing a funeral blues: “I’ve been hearing that, why I don’t know. I’m not here to die. I’d like to live, but the last seven years all I’ve seen is sadness.” That’s not all he saw, of course, but that was what he often felt. He died in 1979. At times problematic, this volume fills in Mingus’s bedeviled story with a generous serving of his words. Readers should perhaps turn to Mingus Speaks after reading Brian Priestley’s Charles Mingus: A Critical Biography, Gene Santoro’s Myself When I Am Real, and Sue Mingus’s Tonight at Noon: A Love Story. They should certainly come to it after listening to Mingus’s music, including Let My Children Hear Music.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. (He plays piano badly.)

Thank you for this fine comment Mr.Ullman.

Having read the aforementioned biographies I ordered this book. Mingus’ memories of Bop years and the psychological-personality protrait of these interview really may complete the great books by Priestey and Santoro.