Arts Interview with Peter Wortsman: The German Imagination of Fear

“There is a difference between blood and guts, as celebrated in the current vogue of horror-slasher flicks, and the capacity of the darkest of the Grimms’ tales to pierce the thin skin of civility and mainline the dark caverns of the collective unconscious.”

By Bill Marx.

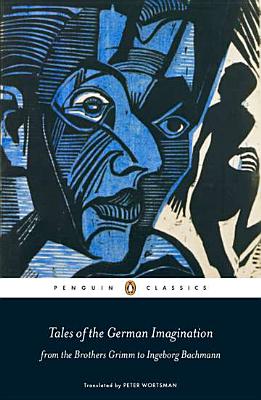

In his introduction to Tales of the German Imagination from the Brothers Grimm to Ingeborg Bachmann (Penguin Books), translator and editor Peter Worstman observes that German writers were “fearless in their readiness to face fear. “ It is important to note that facing fear is not the same thing as creating it, a distinction that takes on particular cultural significance today, given that GGI is grinding out spectacular images of monsters and gore in the movies and on TV. Recent film versions of the tales of the Brothers Grimm, such as Handel and Gretel: Witch Hunters, feed audiences on meticulous images of blood and guts that exceed the outré bounds of nineteenth century nightmares. Our fears have rarely been depicted in such rigorous 3-D graphic vigor.

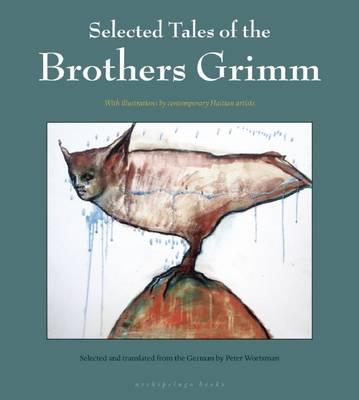

But is visualizing fear the same as facing it? Isn’t that dramatic tension part of what makes the art of fright so memorable? Given the vast array of Hollywood werewolves, vampires, zombies, evil dead and their increasingly ingenious variations, it is important to distinguish the idea of fear as a complex production of the imagination from its manipulative use as a source of edge-of-the-seat sensationalism. Besides his selection and translations of German fantasy tales, Wortsman has also recently published Selected Tales of the Brothers Grimm (archipelago books), fresh versions of the primal texts of European angst.

Because Wortsman has examined and translated 200 years of shudder-inducing prose, from the Brothers Grimm to macabre tales by Rainer Maria Rilke, Peter Altenberg, Kurt Schwitters, Franz Kafka, Paul Celan and others, he is just the man to ask about the appeal of creepy crawlies on the page and the screen. I also questioned him (via e-mail) about the need for new English translations of the Brothers Grimm, what his anthology’s literary visions of madness suggest about the German imagination, and in what ways the literature of terror has changed over the years.

Arts Fuse: In your afterword to The Selected Tales of the Brothers Grimm, you write that many collections of the stories “delete the less savory details and leave out the darkest of the lot, candy-coating the content and tone.” But what about the current rise of Grimm Gore—movies and TV shows that take the violence in the material, via CGI, to places undreamed of in the nineteenth century? What do you think of this anti-Disney fashion? Isn’t the pendulum now going the other way?

Peter Wortsman: Let me admit right off that, while I have seen the posters and ads for this latest run of cinematic and TV takes on things Grimm, the publicity did not tempt me to delve any deeper. Perhaps I am missing something. Last summer on a flight en route to Paris, for lack of more substantial fare, I suffered a snippet of Mirror Mirror, the insipid, campy 2012 Hollywood remake of “Snow White,” with Julia Roberts as the evil stepmother—a film which, in any case, opted for gags over gore and which left no lasting impression.

But in answer to your question, there is a difference between blood and guts, as celebrated in the current vogue of horror-slasher flicks, and the capacity of the darkest of the Grimms’ tales to pierce the thin skin of civility and mainline the dark caverns of the collective unconscious. Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm crafted narratives pared down to the bone. When the evil queen in “Snow White” clamors for the child’s lungs and liver, the reader’s terror is teased, not toyed with: the stepmother’s cannibalistic appetite is ultimately stilled with a fricassee of wild baby boar’s innerds. And when the heroine of “The Girl With No Hands” has her hands hacked off, the reader suspects it’s not for keeps; she grows them back again. It may ultimately be a matter of taste, but I prefer stark allusion to blatant display. And whereas Disney animations normalized, and thus nullified, the raw terror at the root of these narratives, the recent wave of gory Grimm-nastics drowns dread in blood, a bit like the strawberries doused by chocolate fountains at glitzy weddings nowadays.

Arts Fuse: In your afterword, you talk about the “Unexpurgated Brothers Grimm,” but you refer to stories with anti-Semitic content that you didn’t choose to include. Why not make examples of the ugly side of Grimm available?

Peter Wortsman saw a need to scratch away the stucco of kitsch with which Grimm’s tales have been encrusted. Photo: Jean-Luc Fievet.

Wortsman: Again, this is a matter of editorial taste. My purpose was not to show up the Grimms’ collection for its warts and defects but rather to cherry pick what I thought to be the best, including a number of lesser-known, albeit remarkable tales. Not all the narratives are transcendent. Some, like “Der Jude im Dorn” (“The Jew in Thorns”), are coarse Schwänke, or farces, with little redeeming value other than the facile amusement afforded by feeding insidious racial clichés. Such unquestioned clichés were part of the early nineteenth-century folk idiom regrettably recorded by the Grimms without a shrug but hardly unique to them.

Arts Fuse: Did you see a need for a new version of these classics in English? In what ways do your versions differ from others?

Wortsman: I saw a need to scratch away the stucco of kitsch with which these tales have been encrusted in the popular imagination and to reclaim their raw narrative core. So perhaps my aesthetic principle was a bit like that of contemporary architects and interior designers who scrape away layers of plaster, lead paint, tin plating, and aluminum siding to lay bare the beauty of baked brick, hewn stone, and half-beamed ceilings. I sought, while maintaining the archaic flavor of these narratives, most with ancient roots, to reassert a colloquial tone that would echo the generations of untutored tongues involved in their transmission over time. And in choosing to sandwich these texts in between Haitian paintings, as opposed to traditional German illustrations, by juxtaposing dark imaginings I hoped to refresh the reader’s palate, applying the principles of fusion cuisine to literature.

Arts Fuse: In the afterword to the Grimm volume, you argue that children desire “narrative drawn in broad elemental strokes, which acknowledges the mystery, the cruelty, and the terror, encompassing all the dark contradictions of life, and in so doing defangs the threat, vaccinating the ever-vulnerable psyche with denatured venom.” Did this requirement guide the choices you made for the anthology Tales of the German Imagination from the Brothers Grimm to Ingeborg Bachmann?

Wortsman: My criteria for the texts I choose to write and those I choose to translate are always the same. It has to turn me on, to thrill my synapses and make my skin tingle. That having been said, my purpose in assembling and translating Tales of the German Imagination was to gather some of the imaginative lava spewed from the great volcano of the German psyche and in the process, reassemble a rich and prescient literary tradition. I hope that the reader may suffer and enjoy the same skin-tingling thrill.

Arts Fuse: For me, the major strain in the anthology isn’t the tired Freudian terror of sexuality but explorations of madness strung across the centuries, an anxiety rooted in fears of absorption into the mechanical and/or the collective. Did you notice a common ingredient?

Wortsman: The German imagination has always been particularly prone to and fascinated with the ideal. German philosophers and storytellers have kept peeling away the layers of life in search of a pure essence, tinkering with reality to mold a more perfect model. So E. T. A. Hoffmann’s hero, the student Nathaniel, drops his flawed paramour for a bedazzling automaton, Tieck’s mountain wanderer likewise turns his back on the mundane and finds bliss in a false phantasm, von Eichendorff’s young protagonist gets stuck on a statue, Myona’s narrator is engulfed by a magic egg, Walser prefers an imagined kiss to the real deal, Tucholsky’s time-saving device steals more than it saves, and Kafka conjures up a monstrous machine that inscribes life’s sentence on the living.

For Kafka, of course, it’s a metaphor for writing, the double-edged instrument of his delivery and of his torment. For posterity, his imagined penal colony—like the cleft in the mountain, into which the Pied Piper lures Hameln’s children—bears an unsettling resemblance to penal colonies to come. There are false seers at every turn, prophets promising ideal solutions. With hindsight, the reader cannot help but see foreshadowed parallels to the piper and the gray man in Peter Schlemiel in the rantings of a certain corporal with a toothbrush mustache. In all of these tales, the ardent longing for release from the prison of now is coupled with a painful consciousness of the impossibility of escape. Madness is one way out. Laughter is safety valve.

Arts Fuse: The anthology contains some of the usual suspects—Kafka, E. T. A. Hoffmann—but there are also some surprising choices, such as yarns from postwar writers Unica Zürn and Jürg Laderach. Why did you include these texts?

Wortsman: The English language reader imagines that Kafka sprung like Athena, fully grown and armed, from the cranium of German letters. But Kafka had his forebears, his contemporaries and his heirs. While his enigmatic prose has survived, thanks to the machinations of his friend Max Brod, the work of many of his contemporaries has been largely forgotten. So I wanted to serve as a medium, an amanuensis of sorts to resurrect and transmit the silenced voices of authors like Altenberg, Mynona, Klabund, Lichtenstein et al, and in including such post-War scribes as Borchert, Zürn and Laederach, to show that the tradition lives on.

I should add that it is my tradition too. While Latin American Magical Realism was all the vogue some years ago, sparked in part by the marvelous anthology The Eye of the Heart, Short Stories from Latin America, edited by Barbara Howes and published in 1973, harkening back to the dream-rich prose of our own homegrown dreamers, Hawthorne, Irving, and Poe, realism remains the Anglo-Saxon literary norm. I hoped by means of this anthology to shake things up a bit. Full disclosure compels me to admit that a kindred aesthetic informs my first book of fiction A Modern Way to Die (1991), my recent memoir Ghost Dance in Berlin: A Rhapsody in Gray (2013) (See Fuse review), and my forthcoming novel Cold Earth Wanderers (2014).

Arts Fuse: What were the challenges in translating stories that range over 200 years? The prose styles move from the highly artificial to the determinedly minimal.

Wortsman: The key challenge in this case was maintaining a sense of continuity in an amalgam of texts of such disparate voices and styles. Intuition was my only compass. The sense that these texts and their authors were talking to each other, and to us, across time. But aside from various terms and turns of speech that may have meant something else at different times and in different places, the essential task of the translator was and is always the same. I am not wholly conscious of the process when I translate. I try multiple identities on for size. None of them ever fit quite right, but each affords me a temporary release into an alternate consciousness, a kaleidoscopic view of the world through the eyes and skin of another self. In each case, I am obliged to examine, master, and render, not only the syntax and life strategy of the person who spit out those words but also the breathing pattern—for what else are words but exhalations burdened with meaning, and what else are sentences but sinuous signatures of self!

On April 10 at 7 p.m., as part of the Brookline Booksmith Writers & Readers Series, Peter Wortsman will read from Ghost Dance in Berlin: A Rhapsody in Gray, “an elegantly written collection of vignettes” that “crafts a declaration of love for Berlin, a city constantly reinventing itself through circumstance and necessity.”

hi.

you mention “macabre tales” by rilke. didn’t know he wrote any.

harvey

Harvey,

An early story (1894) by Rilke entitled “The Seamstress” is included in the volume. It is a morbid tale that links a desperate hunger for sexuality with madness.

thanks. i hope to read it.

Wow–glad I caught up with this! I look forward to checking these books out. Especially love Peter’s definition of words–“exhalations burdened with meaning.”