Visual Arts Review: Boston Cyberarts’ “The Game’s Afoot” — Something Clever

None of these games engendered any suffering at all. They were already pre-designed for failure; a player has no chance of success. But isn’t part of the pleasure of gaming the repeated failures that, over time, lead to successes?

By Margaret Weigel.

The current Boston Cyberarts show The Game’s Afoot: Video Game Art (through April 14) describes itself as investigating “the nature of art as well as the nature of video games themselves.” It succeeds depending on one’s interpretation of both art and videogames, as well as engagement, craft, and play. The looser the interpretation, the better the chances are that the spectator/participant will enjoy this interactive experience.

The show, curated by Boston Cyberarts director George Fifield, is timed to coincide with the annual gathering of gaming geeks known as the Pax East convention March 22–24 and the curation of the Boston Convention Center’s 80-foot, LED marquee with art from local video game developers and educators. It also takes advantage of an unanticipated gap in gallery programming. The show features six games: Debtris, Into the Void and Sisyphus by local developer Anthony Montuori; O.f.f.i.c.e.A.n.t.s. and Campaign Horse by COLLISIONcollective favorite Rob Gonsalves; and Airlock Park by Brooklynite Victor Liu.

First, is it art? I discussed some of the issues around video games and the art label in an earlier Arts Fuse piece, and even though these games are curated, authored, and displayed in a white-walled gallery accompanied by the traditional wall descriptions, I’m not sure. Again, can we come to a common agreement on what constitutes art? I doubt it. Just for kicks, I looked up the definition of “art” in Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary to make sure that my interpretation was at least in the ballpark. Are these aesthetically pleasing? If you like simple, 8-bit graphics, sure. Did their construction require specialized knowledge? Yes, but in that case, we mean “the art of video games” much like “the art of flower arranging” or “the art of parallel parking.”

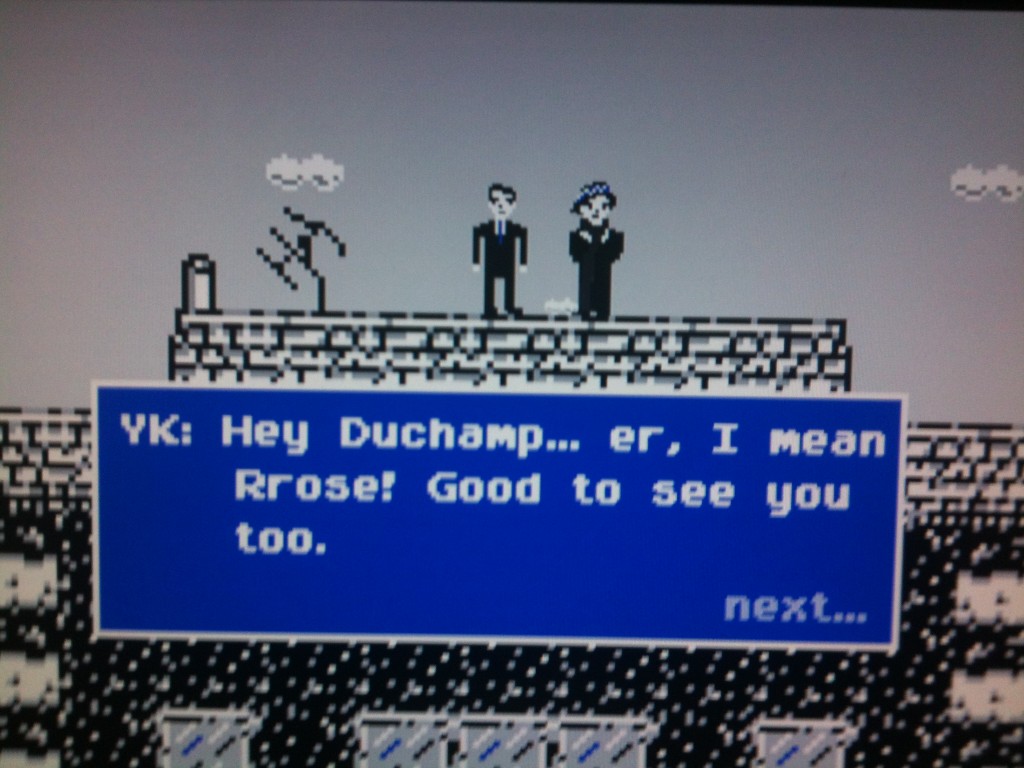

But if they say it’s art, I will take their word for it, the way I took Duchamp’s word for it. Much like traditional fine art before it, game playing is a leisure activity that often takes place with others and can have complex social ramifications.

All six games utilized retro hardware and design—low-res, 8-bit graphics, joysticks and freestanding consoles, old-school controllers, no Wii or Xbox hardware utilized—but it is not clear why. Is this nostalgic requirement intended to be ironic? To mock the high-gloss productions of corporate professional work? To be simpler to construct? To find parts on the cheap? To put design skills honed on older systems to good use? To appeal to an older audience? To indulge in warm memories of playing Missile Command at an arcade in 1982?

Second, are they games? Much of the brilliance of video games has to do with how one interacts with them. These games all assumed a certain level of fluency with the language and hardware of games, that the user understands or can quickly intuit how to operate a joystick, has played Tetris at some point in their lives, etc. This assumption requires that those of us without this mastery, such as most individuals older than 45 and a fair number of women, have learned the rudimentary elements of gameplay if they are going to play.

One of the rudimentary elements of gameplay, according to Roger Ebert—to be fair a cineaste, sure, but not a gamer—is that games by definition have rules, points, objectives, and an outcome: “[game developer Kellee] Santiago might cite an immersive game without points or rules, but I would say then it ceases to be a game and becomes a representation of a story, a novel, a play, dance, a film. Those are things you cannot win; you can only experience them.” While most of these games had points, rules, and a minimal level of player agency, what they lacked was a realistic chance of being able to master them in a satisfactory manner. A recent book, The Art of Failure, is game designer Jesper Juul’s meditation on “the pain of playing video games.” But none of these games engendered any suffering at all. They are pre-designed for failure; a player has no chance of success. But isn’t part of the pleasure of gaming the repeated failures that, over time, lead to successes. Lacking that, the games were less game-like and more like clever animated exercises.

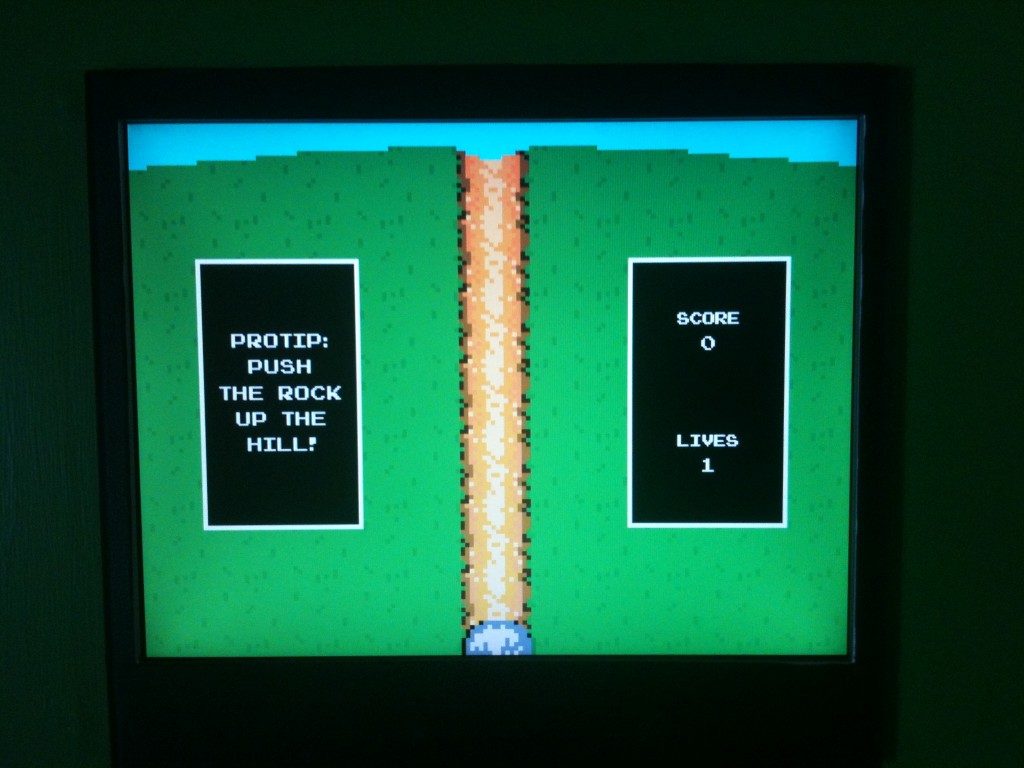

The game Sisyphus asks the user to roll a rock up a hill. Like Sisyphus, I would’ve liked to have at least tried, but the joystick appeared to be broken, and success was impossible. In all honesty, it could’ve been that I just couldn’t operate the joystick properly. I did manage to master the joystick just fine on Montuori’s game Into the Void. The user’s avatar runs into Marcel Duchamp in his Rrose Selavy incarnation; Marcel/Rrose gets to do all the talking, and the user is limited to binary yes/no responses. He at least informs you that you are about to fall off a cliff and that there are some defensive maneuvers that could save your skin. While more game-like in its structure, the experience of watching my avatar fall off a cliff, while enjoyable, was not wholly engaging.

Monturoi’s third game, Debtris, was a chunk of fiscal hopelessness masquerading as a game. The basic construction mimicked the classic Tetris game but with the added caveat that you are trying to pay down your huge student loan and will be compensated for each row you successfully fill with cubes. Someone with actual Tetris experience will fare better than me; I put down the controller after my first income check-in and decided that I had just spent five minutes of my life that I would never recoup. All of Montuori’s work are meditations on futility and, in the case of Debtris, highlight the serious issue of student indebtedness. But a frustrating game with no chance of success is not fun to play.

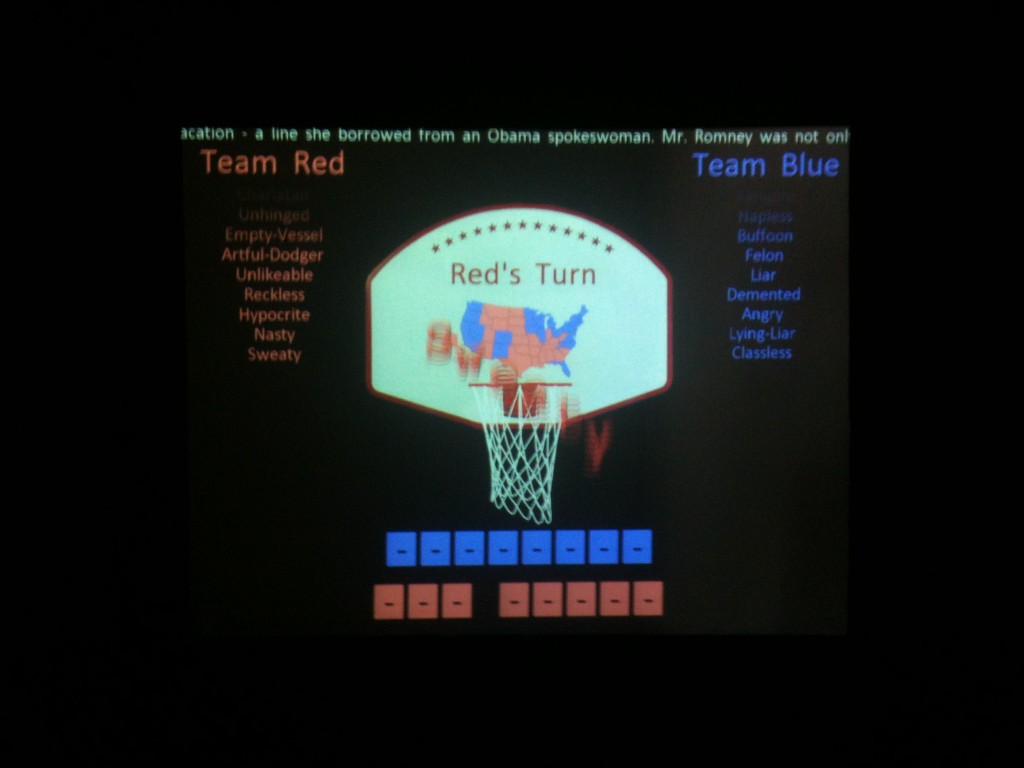

Rob Gonsalves’ game O.f.f.i.c.e.A.n.t.s. continues this theme of work-inspired angst; when the user “shakes” the Office Worker Kibble into the maze (caution: don’t actually open the canister!), small human figures rush over to “eat” it. I get it: corporate cube life sucks, and success/release is impossible. Gameplay was minimal. Conversely, I couldn’t lose Campaign Horse for trying. Campaign Horse is a digital version of the classic playground game, where the user flings a rigged basketball towards a screen-based net to earn a letter. Two teams—the red and the blue—represented the political parties, and the winning team got to trash the defeated in a media frenzy.

Confession: I used to be a freethrow basketball champion, and my shooting prowess initially did not faze me. But when I tried to miss, I still made the shot. I felt a little cheap once I realized that that there was zero skill involved (or maybe I’m that good). Campaign Horse may have been the most confusing of the six video games. Why do all my shots go in the basket? What words are being spelled out? Who are these virtual team members listed on each side? Why do six baskets trigger the media blitz and not five as in a traditional game of Horse? Oh, my head.

Finally, Victor Liu’s Airlock Park consisted of a 3-D rendered screen space and a controller that allowed the user to navigate through the space. The description states that “this work pulls image fragments from many sources—from cinema and art history to internet video and video game footage—to construct virtual tableaux, or scenes,” i.e. the user is randomly presented with a montage of visual materials. The caption on the wall plainly stated that it followed traditional gaming conventions, but which ones? Not the ones about rules, a goal, and the opportunity to fail and succeed.

I suspect the gamers at Pax East may enjoy these video games. I heartily recommend that they set foot outside the convention center and take a trip to Jamaica Plain. I suspect others may enjoy these as well, but I would suggest that they are easier to appreciate in concept than in practice. I wish the Cyberarts Gallery had been less forthcoming about the games and their intentions and allowed me to discover their limitations for myself.