Poetry Review: Yvan Goll’s “Dreamweed” — Visions of a Shape-shifter

Yvan Goll may be the great shape-shifter, the Zelig, of twentieth-century poetry.

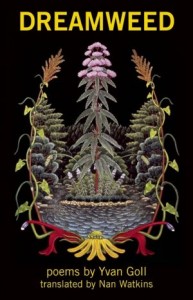

Dreamweed: Posthumous Poems by Yvan Goll. Translated from the German by Nan Watkins. Black Lawrence Press, 140 pages, $17.

By Jim Kates

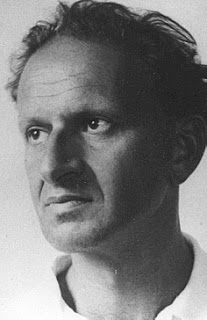

Yvan Goll may be the great shape-shifter, the Zelig, of twentieth-century poetry. Born Isaac Lang (or Lange) in 1891 in the ambiguous, French-German borderland of Lorraine, he was deftly bilingual, writing with ease in both French and German. He also moved through every major artistic movement of the 1900s, from Swiss Dadaism and political pacifism to French Surrealism and German Expressionism, finally coming to New York (via exile) at the beginning of World War II. Despite these high gloss cultural connections, his profile has remained remarkably low, at least in contrast with the acclaimed writers he moved among. In the late 1940s he returned to Europe; he died of leukemia in 1950.

It is the German poems of Yvan Goll’s last years (Das Traumkraut) that Nan Watkins has translated in Dreamweed. Recently I had occasion to review for The Arts Fuse Mahmoud Darwish’s In the Presence of Absence, a “self-elegy” of poems written by a poet knowing his death is imminent — an established genre in Arabic. Dreamweed is a European contribution to that distinguished tradition.

While Goll’s poetry stretches and engages the German language in ways analogous to those of his famous contemporaries Nellie Sachs and Paul Celan (whom Goll’s widow later accused of plagiarizing from her husband), his linguistic energy tended toward a playfulness that is largely missing in the knottier poems of the latter (Disclosure: I have translated a number of Goll’s French poems.) But this friskiness had pretty wel burned off by the time of Dreamweed, and these poems take on their own Johnsonian urgency regarding mortality.

Es hat der Schnee über Nacht

Meine Totenmaske gemacht

Overnight the snow

Made my death mask

(“Snow Masks”)

Dreamweed is filled with vegetable and mineral elements. Animal references often come off as hostile (“The laughter of the larks makes me shudder” “Sacrificial animals roar deep within me / And beef loins exhale their stench”), but earth, air, fire, and water are embraced as “Geliebte,” “My beloved.” There is one terribly important absence:

My mouth still houses

Century-old magic

In my ears I hear a ringing and a singing

And no God

As the sequence picks up steam, it discovers love, personified in Goll’s wife, Claire, as in this poem, which elaborates on images that originated earlier in the poet’s work:

Beloved, you are my river

On your right bank is the past

On your left bank is the future

Streaming together we sing the present.

Dreamweed ends on complex visions of a fragile permanance:

I’ll have the saga of our love preserved in quartz

The gold of our dreams buried in a desert

The dust-forest (Staubwald) is getting darker and darker

Watch out! Don’t touch this dust-rose (Staubrose)!

I have drawn attention to some of the German words in this last, sensitive poem because they point out the challenge that confronts the translator of Dreamweed. The German word Staub is certainly “dust,” which implies the mortality of the sequence — dust to dust and ashes to ashes. But Staub can also be “pollen,” a natural association with trees and roses, and that notion of potentially fruitful seeding seems to me equally implied here in the word Staubrose. Watkins has made a significant choice that tilts Goll’s ambiguous meaning (death/life) in one direction. Goll is not so resolutely material.

There are other points of questionable interpretation, such as when Watkins translates “Blick” as “leer” in “Explosion of the Marsh Marigold.” The original German word conveys a far more neutral expression, and the translator has clearly been influenced by “Lüsternheit” – lust – in the line that follows. There are other instances of awkwardness — “And barely do I glance from one to the other / Than I have become an old man” — clanks and clatters in a way that the original German does not. The line “Redeem us, orange day planet!” sounds more than a little curious. And there are points of cowardice — not taking on the careful rhymes in “Schnee-Masken,” for instance.

Still, for the most part, Watkins has brought the German across into English more than creditably — and credibly. And, for all of my reservations and those of other readers, the Black Lawrence edition provides the original German text.

Jim Kates is a poet, feature journalist and reviewer, literary translator and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a non-profit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book is Muddy River (Carcanet), a translation of verse by Russian existentialist Sergey Stratanovsky. His translation of Mikhail Yeryomin: Selected Poems 1957-2009 (White Pine Press) won the second Cliff Becker Prize in Translation.

Tagged: Black Lawrence Press, Dreamweed, Nan Watkins, german, translation