Book Review: Mahmoud Darwish — Palestinian Poet of Heritage and Exile

Mahmoud Darwish, who died in 2008 at the age of 67, was best and heroically known for his complex perspective on political and spiritual borders—as both a poet and a spokesman for his Palestinian people.

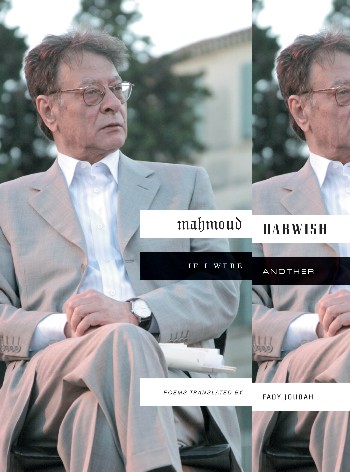

If I Were Another by Mahmoud Darwish. Translated from the Arabic by Fady Joudah. Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 201 pages, $28.

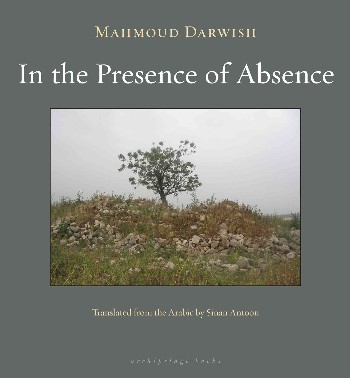

In The Presence of Absence by Mahmoud Darwish. Translated from the Arabic by Siman Antoon. Archipelago Books, 171 pages, $16.

By Jim Kates

Among the few unambiguously pleasant memories of my one visit to southwest Asia a few years ago, to the land that the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish claimed as his own by heritage and exile, was an early morning walk I took along the militarized cease-fire line between Israel and Syria near an occupied border resort settlement called by the Israelis Neve Ativ. Back and forth across the barbed wire flitted a striking bird I had never seen before, black and white with a curious golden crest—Upupa epops when I looked it up in a Hebrew bird-book that didn’t give me the English name—a hoopoe, as I learned soon enough; and then, of course, I knew it from other reading. That particular hoopoe has remained for me the symbol of the inadequacy and purposelessness—and the menace—of political borders. It is also the title and the central image of a major poem in If I Were Another, a collection of Mahmoud Darwish’s longer poems translated by Fady Joudah; and, if it were not for an important difference between ignorance and consciousness, the bird might be a fitting symbol for the poet himself, a native of the region, displaced but not grounded by geopolitics, spectacular, almost gaudy, in his plumage.

. . . How we wish. We wish. Perhaps

we’ll fly one day . . . humans are birds that don’t fly. And the earth

is larger when we’re ignorant, smaller when we know our ignorance.

Darwish, who died in 2008 at the age of 67, was best and heroically known for his position on the border—a poet and a spokesman for his Palestinian people, his politics and art so intertwined that even just reading him can feel as much like a political act as taking a morning walk in disputed territory. In his introduction, Joudah underlines “a private speech become collective.” This kind of celebrity may obscure the individuality of a poet’s voice—we read the symbol, not the word. But, if the personal is the political, in Darwish’s case the reverse is also true: the political is personal—“We and our country are one flesh and bone”—and the collective speech issues from a private voice. It is the first-person singular pronoun that dominates the poetry in If I Were Another.

Who am I?

The Song of Songs

or the university’s wisdom?

Both of us are me . . .

and I am a poet

and a king

and a sage on the well’s edge,

no cloud in my hand,

no eleven planets

on my temple,

my body is fed up with me,

my eternity is fed up with me,

and my tomorrow

is sitting on my chair

like a crown of dust

No matter how politically they are written or are read, Darwish’s poems call for a reciprocal, first-person reading. Engaging with him is much more explicitly a dialogue than with many other poets—a dialogue of exchange of experiences. (Joudah calls Darwish “a playwright at heart.”) And sometimes it seems as though the experience that lurks underneath almost all of his poems is tomorrow’s crown of dust.

In the Presence of Absence, first published in Arabic in 2006 and here translated by Sinan Antoon, features a trio of persons: the “I” who speaks, the sometimes overlapping “you” to whom this long sequence of 20 “texts” (apparently Darwish’s own neutral description of its form) is addressed: “Who are you on this journey?” is a question raised but never specifically answered.

Allow me to gather you and your name, just as passersby gather the

olives harvesters forgot under pebbles. Let us then go together, you and I, on

two paths:

You, to a second life promised to you by language, in a reader who might

survive the fall of a comet on earth.

I, to a rendezvous I have postponed more than once with a death to whom I

had promised a glass of red wine in a poem.

And then there is a third person—sometimes “one,” eventually also “she:”

I asked you: Who is she? You said: She has so many selves that I myself do not know her. She and not she. She and her personæ, when they come together in a love poem, that draws on many sources, searches for the fulfillment of what cannot be fulfilled…. She and not she; she is present and absent, it is as if her presence holds my absence within her, and her absence carries the presence of details.

The words spill over from the lyrical prose meditation of a love-song into codas of verse, ultimately situating the poet on an unmarked boundary between life and death. Antoon reads them as premonitory: “Thinking this might be his final work, [Darwish] summoned all his poetic genius to create a luminous text that defies categorization.” The translator points out that self-elegy is a “an established genre” in Arabic poetry, and In the Presence of Absence is an expansion of this tradition. Otherwise, it certainly does defy categorization; and, if the unorthodox volume exudes the perfume of finality, it is with the sweetness of a rich dessert.

The reader not already familiar with Darwish would do best to begin with If I Were Another. Joudah provides a comprehensive general introduction, useful attention to each of the “lyric epics” the edition offers, a helpful apparatus of notes, and an extensive glossary. Antoon’s introduction and notes are far more discursive and equally informative, but the work reads best in the wider context of the poet’s discourse.

Darwish deserves to be—needs to be—read. His absence from even so recent a reference book as the 2000 edition of the Columbia Encyclopedia indicates a neglect that may have its origin, like so much of his work, in metaphorical, barbed wire fences or just in general cultural myopia. Nevertheless, we can give him a permanent home in our consciousness.

So good to see a review of these two books! I have read and read again “If I Were Another”.

Adina Hoffman’s biography of the late Palestinian poet Taha Muhammad Ali contains some interesting information about Darwish and his contemporaries.