Dance/Movie Review: The Passing Parade — A Film about the Joffrey Ballet

The new documentary, Joffrey: Mavericks of American Dance, derails, partly because its hagiographic tone encourages elisions that beg important questions.

Joffrey: Mavericks of American Dance (2011). Directed by Bob Hercules. Narrated by Mandy Patinkin. Lakeview Films, 82 minutes, in limited release.

By Debra Cash

Robert Joffrey was seven years old when he was taken to a touring performance of the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo. Those tours inspired a lot of young girls and boys to dream of becoming dancers or even choreographers, but that’s not what got young Bob—the child of an Afghan restaurant owner and an Italian mother—going. He went home, sat down, and made a list of what ballets he was going to program when he ran a ballet company of his own.

It’s hard to remember the impact America’s “third” major ballet company had on our dance life mid-century. Joffrey was blessed, and cursed, to be running a ballet company on a shoestring in the shadow of Balanchine/Robbins excellence—one of the great founts of dance creativity in all of dance history—and the defector-and-star extravaganza of the deep-pocketed American Ballet Theatre.

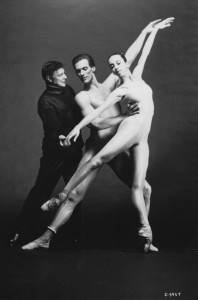

He, and the man who became his lover and then, for the next 40 years, his professional alter ego and resident—and less than brilliant—choreographer, Gerald Arpino, carved out a very special cultural niche. It introduced the fusion ballet, inviting Twyla Tharp to create her first ballet for the Joffrey’s ballet dancers performing alongside her contemporary ones: Deuce Coupe was set to the Beach Boys and featuring a graffiti-tagged set. It played up psychedelia in the extravagant 1967 Astarte, a fever dream of a “rock” ballet that ended with a multimedia coup de theatre that followed the hero out the stage door and down 56th Street. But most important, it was the Joffrey Ballet that repaid the little boy’s debt to history by reviving and celebrating the great, nearly lost works of an earlier time: Kurt Jooss’s breathtaking antiwar The Green Table, a historically informed revival of the lost Nijinsky Sacre du Printemps, and what former New York Times dance critic Anna Kisselgoff calls “the granddaddy of modern art ” and collaborative avant-garde theatre, the Massine-Picasso-Cocteau-Satie Parade.

The story of the Joffrey Ballet, established in its first iteration in 1956, has been called the story of the little engine that could, and I would add that when one track was blocked, the little train kept on going.

But the new documentary, Joffrey: Mavericks of American Dance, derails. It combines a hagiographic tone with elisions that beg important questions; its proportions seem dictated more by the availability of colorful archival footage than well-thought-out narrative decisions; and the dancers, so young and beautiful in their dancing days, are shot and edited thoughtlessly, even cruelly, in less-than-inspiring interviews. (I’ve been a talking head in documentaries myself, and at the very least, the speakers ought to have been encouraged, and helped, to look their best.) Of the veterans, only the poised and intelligent Trinette Singleton, who tells a wonderful story of rushing out to a newsstand to see herself on the cover of Time Magazine, the mercurial-grown-thoughtful Gary Chryst, and Christian Holder, who speaks with the basso molasses accent of his uncle Geoffrey, come off as well as they deserve.

The painful intricacies surrounding what happened when the company’s patroness, Standard Oil heiress Rebekah Harkness, pulled her money to start a competing troupe and took most of the dancers with her, is painful, if understandable all around; the company’s bet-the-house-and-raise-the-money foray into a kitschy program to music by Prince is defended with faint praise, and we see the troupe’s shiny, new home in Chicago and the 2008 dedication of a studio named for Arpino, who is helped, teetering, toward the plaque looking like Jooss’s costumed Death.

It’s a wash: if you’re interested in the Joffrey and its legacy, there isn’t enough about how this company helped create and fed into the dance boom of the 70s and 80s and not enough footage of the idiosyncratic dancers who made up its ranks and the broad repertoire that established its excellence. If you’re not aware of the Joffrey or interested in how classical ballet tried to cross the bridge into pop culture, the lack of people you’d want to know better—like, for instance, the adorable and cantankerous elderly dancers in Dan Geller and Dayna Goldfine’s Ballets Russes—will leave you cold.

Debra Cash, a a founding contributor to the Arts Fuse now serving on its Board, is Executive Director of Boston Dance Alliance. She also serves as a Scholar in Residence at the festival Ted Shawn founded, Jacob’s Pillow, which holds many of the archival materials used in Ted Shawn: His Life, His Writings, and Dances.

c 2012 Debra Cash

Tagged: documentary, Gerald Arpino, Joffrey Ballet, Joffrey: Mavericks of American Dance

As always, enligtened, inciseful, and informative criticism.

I was also disappointed. I expected a film much more focused on Robert Joffrey, the early company, Harkness foreign tours, City Center years. So many fascinating stories,experiences, themes neither questioned nor explored. Another film waiting in the wings? Yes, unfortunately, not even close to the magic of Ballets Russes.

Thanks, Karen and Marie!

For Arts Fuse readers, some of the livelier and more revealing stories of those early Joffrey years are included in Marie’s memoir, Ballet to the Corps (2008); in full disclosure, I made some suggestions on a very early draft. It’s available from Amazon.

A couple of quick corrections: Joffrey as a boy saw the Denham Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, not the Ballets Russes; the Joffrey Ballet started before Ballet Theater became defector/star studded and before the Robbins/Balanchine partnership. I should know: I simultaneously danced with the Joffrey and with Robbins’ Ballets:USA, his own company before he was permanently affiliated with NYCB.

I agree that some of the interviews were less than inspiring, but there are many other alumni of the company that might have made better interviewees had they been invited to do so. I do think Ms Cash is more interested in how people look than in what they have to say, however. Let’s remember that the early dancers are all in their 70’s now and, unlike the Ballets Russes survivors (of whom I am also one, and yes, I was in that film), for the most part, we worked long and hard for most of our lives, without the luxury of wealth to help us look glamorous. In fact, doesn’t that add to the “little engine that could” narrative? I also object to the cruelty of the description of Gerry Arpino looking like Jooss’s Death. Was that necessary?

The big difference between the two films is that Ballets Russes was the story of a reunion of the dancers, a grand and glorious party in New Orleans, not a history of the company, while the Joffrey film attempted the near-impossible task of compressing 50 years into 1 & 1/2 hours. Oh, and, by the way, I thought Françoise Martinet looked as glamorous and spoke as movingly as anyone else in the film.

Even the “mavericks of American dance” theme could have been better served. One example: A “where are they now” re the original 6 Joffrey dancers. (The iconic photograph of the 6 was shown in the documentary.) It would have revealed that one dancer, Glen Tetley, became a modern/contemporary dance choreographer with a long career, both here — notably at Ballet Theatre — and in Europe. An interesting clue to Robert Joffrey, the maverick’s interest in hiring modern dance choreographers?

I understand that compressing a 50 year long story into documentary length must be very difficult. But, is it not possible?