Short Fuse: Robert Stone’s ‘Fun With Problems’

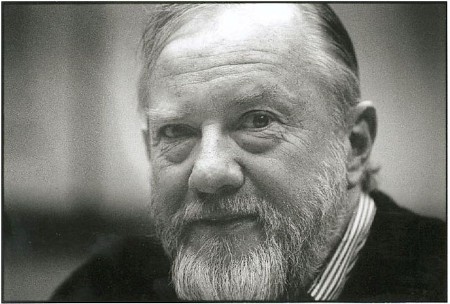

American author Robert Stone is attuned to the havoc latent in masculine pride and to the hostility likely to break out for no particular reason between males of our species.

Fun With Problems: Stories by Robert Stone, Hougton Mifflin Harcourt, 195 pages, $24

Fun With Problems: Stories by Robert Stone, Hougton Mifflin Harcourt, 195 pages, $24

Though one of our prose masters, Robert Stone is less acknowledged than he ought to be. That may be because his characters repeatedly court or are caught up in dangerous situations, often pertaining to war, sexual obsession, or drugs, which may lead him to be downgraded as a genre writer.

The more likely reason for his relative obscurity is that in the United States today any but the most obviously Nobel Prize worthy writer—perhaps only Phillip Roth, since John Updike is dead—has a hard time getting full credit. Our taste tends to veer away from real writing toward colostomy bags in literary form penned by the likes of Dan Brown.

But back to Stone. Dog Soldiers (1974)—well served by the film “Who’ll Stop the Rain,” starring Nick Nolte—and Outerbridge Reach (1992) are his best novels. His memoir, Prime Green: Remembering the Sixties (2006), wouldn’t be a bad place to start getting to know him either since it contains many of his lifelong concerns, including Vietnam, drugs, physical-edge and psychological-edge play, ocean, irony, and varying shades of disappointment.

To give some sense of the pleasures Stone’s prose routinely delivers, I quote a sentence from Prime Green about the Adelie penguins he observed in Antarctica while serving in the U.S. navy: “They come at the persistent intruder, cackling Donald Duck-like, fowl obscenities and churning their flippers faster than the eye can see, like so many tasteful little pinball machine components. A good shot with the flipper, however, can buy them back a little respect, since they’re capable of breaking a human leg with one.”

Stone would never be drawn to the long-suffering birds ennobled by Hollywood penguin operas. It’s only the sort of gangland fowl you’d cross the street to avoid that get his attention. There is no more bird-watching in Prime Green; instead, plenty of Ken Kesey watching. Kesey’s Magic Bus, filled with Merry Pranksters “painted all colors,” came to rest, after its cross-country journey, outside Stone’s Manhattan apartment.

The name Prime Green comes from the dawns beheld in Mexico’s Manzanillo Bay by Stone, Kesey, and their crew. Such dawns, Stone writes, made “nonsense of examined life.” All caught in their “vortex” would “freeze in [their] tracks and stand to, squinting in the pain of the light, swearing, grinning. We called that light Prime Green; it was primal, primary, primo.”

The phrase “you’re on the bus or you’re off the bus” may be next to meaningless today, but those curious about what the ride might have been like will get some good clues from Stone’s prose.

![]() Fun With Problems, Stone’s new collection of short stories— after Bear and his Daughters (1997) and Bay of Souls (2003)—wouldn’t be a bad place to start with him either. Certain things come clear about the roots of his trademark irony in the current volume. Here, for example, is Duffy, the main character of “The Archer”, as he prepares to attack his wife and her lover with, as campus legend has it, a homemade bow and arrow, while screaming: “All right, motherfuckers. Cupid is here.”

Fun With Problems, Stone’s new collection of short stories— after Bear and his Daughters (1997) and Bay of Souls (2003)—wouldn’t be a bad place to start with him either. Certain things come clear about the roots of his trademark irony in the current volume. Here, for example, is Duffy, the main character of “The Archer”, as he prepares to attack his wife and her lover with, as campus legend has it, a homemade bow and arrow, while screaming: “All right, motherfuckers. Cupid is here.”

Though hell-bent on mayhem, Duffy, an artist and art historian, is not too far gone to mull over his motives. “He might have been defending his home and his wife’s heath and safety,” he reasons, half-sanely. But he “knew better in these weak piping times than to speak of honor.”

Here Stone betrays his own longing for a less weakly “piping” time, a time when honor could be invoked without embarrassment, and irony, therefore, was not such a constant and merciless commentary on our limitations.

Some stories in this collection are meant to date themselves by the prevailing intoxicants—meth, grass, alcohol, acid, freebase, crack. Dope for Stone serves much as tree rings do for a redwood fancier; they track circumstances and environment, always of historical concern to Stone. “High Wire,” for example, begins with the narrator telling us the main event of his story occurred “about midway between the death of Elvis Presley and the rise of Bill Clinton.”

Stone is attuned to the havoc latent in masculine pride and to the hostility likely to break out for no particular reason between males of our species. One timely story records the sort of fierce dementia that can lead one man to fly his plane into an IRS building, and another to shoot up guards at the Pentagon because it is an article of faith for him that 9/11 was a crock cooked up by a malevolent government.

In “The Wine-Dark Sea,” a man named Taylor exclaims rabidly, apropos 9/11: “That was faked, wasn’t it? The planes into buildings . . . “I knew it! . . . No planes whatsoever!” If Taylor read at all, his taste would run toward conspiratorial mish-mash—say Dan Brown, but more murderous.

Robert Stone: his lifelong concerns include Vietnam, drugs, and varying shades of masculine disappointment.

My favorite story in Fun With Problems is the concluding tale already mentioned, “The Archer.” Stone’s prose is unbridled here as it records what appears to be Duffy’s irresistible rush toward implosion. Years after attacking his wife, Duffy is piecing himself together but coming apart anyway, maybe faster. Arriving at Pahoochee State University on the Gulf Coast to give a lecture, he’s sickened by what he perceives as the local blend of sanctimony and ugliness:

Insolent posters were affixed to [the] suffering trunks [of trees] with cruel nails the size of industrial staples, threatening passersby with the judgment of Christ. Artificial palms stood at intervals among the others like Judas goats at a slaughterhouse to encourage and betray the doomed natural ones.

Duffy’s Pahoochee hotel room provides no relief, with water from the faucet tasting “of baitfish and the Confederate dead.” Duffy’s academic host—a Professor Rind, yet—calls to say he’d like to bring his kids up to the room since they’d enjoy the ocean view and the elevator ride. By then, though, Duffy has drunk himself past the line separating “inebriation and riot”. He says: “Maybe they’d like it if I threw them out the fucking window. How many are there?” That appalling addendum—“How many are there?”—strikes me, at least, as priceless.

Duffy, in the dining room, blows up and declares that the crab being served is nothing but “some rotten thing out of a tube. Made by people who hate us and think we’re stupid.” This outburst brings the chef roaring out of the kitchen and mortifies Rind, his family, and a hapless, young waitress. Duffy never gets to deliver his talk on “contemporary American painting, more or less, and how it got that way.” Instead he does something that neither he nor the reader would have thought possible for him, and that might be called redemptive were Stone a more explicitly religious writer.

That Stone makes this unexpected act fully credible and rewarding is one reason Fun With Problems is such a good read.

A review of Prime Green and an interview I conducted with the author for The Boston Globe can be found here.

Tagged: American, Dog Soldiers, fiction, Prime Green: Remembering the Sixties, Robert Stone