Book Feature: A Conversation with Claude Lanzmann about his memoir, “The Patagonian Hare”

Claude Lanzmann is a great raconteur who’s honed his narrative skills as a veteran journalist. His memoir is exuberant and provocative at its best, bombastic and superficial at its worst.

By Helen Epstein

Claude Lanzmann—the French writer, editor-in-chief of Les Temps Modernes, and film-maker best known for his nine-and-a-half hour film Shoah—was in Cambridge last week to promote his book of memoirs The Patagonian Hare (FSG, 544 pages, $35). He proved to be a cranky conversationalist. Billed as “A Conversation with Claude Lanzmann,” the event turned out to be more of a feisty monologue. But when you’re 86, still working, and are regarded by some as a cinematic genius, tout est permis, at least the audience of about 200 Harvard professors and students seemed to think so.

Lanzmann’s book, The Patagonian Hare is a looping, uneven marathon of story-telling by a secular French Jew and alpha-male: A loosely chronological set of reminiscences that Lanzmann dictated to a colleague over two years, it was published in France in 2009 and became a best seller there. It’s easy to see why. It’s packed with people (like Jean-Paul Sartre and lesser known philosophes) dear to the French and dramatic episodes of courage, cowardice, and coming of age in the Resistance. Although Lanzmann does not absolve himself of cowardice—particularly when, as a boy, he did not step forward to defend a classmate from anti-Semitism—mostly he presents himself as hero, fighter, and bon vivant (“Even if I lived a hundred lives, I wouldn’t be exhausted”).

He’s a great raconteur who’s honed his narrative skills as a veteran journalist. Hare is exuberant and provocative at its best and bombastic and superficial at its worst, set against a changing, twentieth-century backdrop that includes the second world war, the Cold War, the Korean war, the Algerian war, several Israeli wars, and Lanzmann’s personal 12-year war to make the film Shoah.

He was born November 27, 1925, the grandson of Russian Jews who fled pogroms and conscription in the great westward Yiddish-speaking migration at the turn of the century. “In a sense, I am of old French stock,” he writes, in one of many instances where he seems ignorant of Jewish history, including French Jewish history. “My father was born in Paris on 14 July 1900, my family has been in France since the late nineteenth century; I would go so far as to say that I feel so securely French that Israel has never been problematic for me as it has been for the more recently assimilated Jews who arrived in France between the wars or after World War II. . . . Going to Israel revealed to me that I was both innately French and yet also coincidentally French, not at all of old stock.”

His parents were unhappily married; his mother Paulette left his father and her three children when Claude was nine. They were raised by his father, a politically prescient man who drilled his kids in escape techniques and arranged for their safety during the Nazi Occupation.

In 1943, although he already had earned his baccalauréat, Claude was sent to a boarding school in Clermont-Ferrand. Unbeknownst to his father, Claude had joined the jeunesses communistes already, although he had not yet read the literature. His father, unbeknownst to him, was already a member of the Mouvements unis de la Resistance. This is well-covered ground by now, and Lanzmann does not dwell on it. Wisely, he spends as much time describing his unusual family, especially his difficult and wildly unconventional Jewish mother Paulette. “I was nine years old when, coming home from school with my [younger] brother and sister, I found our house deserted,” he writes, in the understated way he chooses for personal matters. “My first reaction was one of relief rather than sadness: my parents’ arguments had grown so frequent and so violent over the years that I lived in fear that the worst would happen, murder perhaps, or suicide. That was in 1934. At the time, those women who, appalled by the conditions imposed on them by marriage, dared to throw cautions and security to the wind, to leave their husbands and their children were extremely rare; one had to be made of steel to brave the stigmatism and the daily heroism to which they were condemning themselves.”

All true, but it is surely the later judgment of the man who became Simone de Beauvoir’s lover at the age of 27, rather than the experience of an abandoned child. Passages like these made me realize the many differences between memoirs and memoir: the former an extended, self-styled epitaph; the latter a quest for self-understanding.

All of them—both Lanzmann’s parents; his father’s partner, Helene; his mother’s companion, the poet Monny de Boully; and the three children—survived the war. Father and stepfather together escort the young Claude to his first fancy brothel. Monny prevails upon a friend to get Claude admitted mid-term to the prestigious Lycee Louis-le-Grand, on track to the Ecole Normale Superieure, and stage manages his first affair by picking up a beautiful woman in the street and inviting her to consider his step-son. “Seduction is not generally a family activity,” Lanzmann writes, but Monny “sang my praises, making me an object of desire.” They brought her home to meet Paulette and, a week later, Lanzmann had a mistress.

Claude’s younger sister Evelyne’s love affairs were also inextricably tied up with family. Raised by Lanzmann père and her Catholic stepmother Helene, Evelyne arrived in Paris at 16 and promptly fell in love with a series of her brother’s friends and colleagues including, eventually, Jean-Paul Sartre. Evelyne, an actress, toured with road companies and performed in Sartre’s plays. Sartre fell in love with her, and offstage, the two had a secret liaison, monitored and clucked over by Claude and Simone de Beauvoir. Evelyne appears to have been deeply wounded by the repeated rupture of attachments that began with her mother. She killed herself in 1967 at the age of 40, and Lanzmann’s chapter about her is the most tender and affecting in the book.

Hare is deliberately non-linear so it’s very hard to keep track of dates, but at about the time Evelyne arrived in Paris, Lanzmann fell passionately in love with actress Judith Magre, who in his account up left him after six months and disappeared without a trace. The result, he writes, was that he failed his exams for Ecole Normale and instead studied philosophy at the Sorbonne. Student friends invited him to Tubingen, and he had his first encounter with Germans after the war. It was 1946, so he must have been 20 or 21 when he was invited to spend a week-end at the estate of the von Neurath family, dined with former Wehrmacht officers, and stumbled upon a small concentration camp located on the property. Although he describes what it looked like, Lanzmann doesn’t get into its impact on him. Nor does he explain his decision to take a teaching job in the French zone of West Berlin, becoming a lecturer at the recently-founded Free University.

He spent at least two post-war years there teaching philosophy, French, and a course on anti-Semitism that students asked for, using Jean-Paul Sartre’s Reflexions sur la Question Juive as a text. This book had been important to him when he was a teenager, and he assigned it now to German students, some of whom had returned from military service. “I was identical to the Jews described in it, raised outside any religion, any culture that might be called Jewish.”

But Lanzmann writes little about their discussions. Instead, he relates that he wrote an expose of the failure of de-Nazification at the university (reprinting or at least describing it would have been a good idea). That led to more freelance work back in Paris and to the offices of Sartre’s Les Temps Modernes. By the summer of 1952, he had established himself as a journalist and become the lover of Simone de Beauvoir (“We lived together as a married couple for seven years, from 1952 to 1957, I am the only man with whom Simone de Beauvoir lived a quasi-marital existence.”)

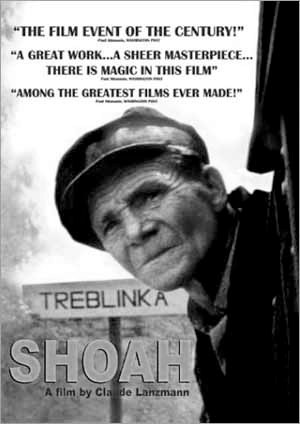

In 1952 Lanzmann also made his first trip to Israel. Though he has never learned Hebrew, he made his first film about the country in 1973: Israel, Why. That documentary led to his working for 12 years on Shoah, first screened in 1985, still internationally regarded as a milestone in film-making, and just broadcast on television to five million Turks and untold numbers of viewers in Iran.

French alpha-male and director Claude Lanzmann — his memoir is a looping, uneven marathon of story-telling. Photo: Anne-Christine Poujoulat/AFP/Getty Images

At 86 Lanzmann looks great for his age: good head of gray hair, no glasses, short and erect—a bit like DSK. He said, in accented English, that he had a fever of 38.5 Celsius. Perhaps he wanted to let his audience know he was too sick to be bothered with questions. He delivered a monologue, based on his book, and, despite the best efforts of the moderator, stuck to his script.

He deflected most questions with a terse, “Read the book,” or “See the film,” so it was easy to jot down the few responses he deigned to make:

“Shoah is not a documentary. The word makes me want to take a pistol and shoot.”

“I could never have made Shoah if I had been in a camp. Shoah is not about survival. It is not about survivors. It is about death.”

“I say, when I want to be provocative, nobody was in Auschwitz. The people who were selected to leave did not experience Auschwitz. The people who died had no consciousness of their own death.”

“If you make a film like this, you cannot respect the rules of a cricket player.”

“When a Chinese film-maker asked me how I would make a film about Nanking, I told her ‘Go to Japan.'”

Why is the book called The Patagonian Hare?

Lanzmann deflected this question too but, in mellifluous French, recited word-for-word the long epigraph to his book. It’s from The Golden Hare by Silvina Ocampo, where the hare is hounded by a pack of dogs. “‘Where are we headed?’cried the hare. ‘To the end of your life,’ howled the dog in dogs’ voices.” He described filming two hares in Birkenau who seemed initially stumped by the dense barbed wire, then able to find a way through it. Then he recalled and an encounter with yet another hare while driving in Patagonia.

“Though I know how to see,” Lanzmann writes at the end of his memoirs, “though I am gifted with a rare visual memory, the spectacle of the world, or the world as spectacle, always relates for me to an impoverishing dissociation, an abstract separation. . . I have thought about hares every day as I was writing this book: those hares in the extermination camp at Birkenau that slipped under those barbed-wire fences impassable to man: those countless hares in the great forests of Serbia. . . the mythic animal that appeared in the beam of my headlights just outside the Patagonian village of El Calafate, piercing my heart with the fact that I was in Patagonia, that at this very moment Patagonia and I were true together.”

Helen Epstein is the author of Children of the Holocaust and Editorial Director of Plunkett Lake Press eBooks , an electronic press specializing in books about Central Europe.

Tagged: Claude Lanzmann, Culture Vulture, documentary, french, Jewish, memoir, Shoah