Concert Review: Lowell House Opera Presents “Snegurochka”

Although there is room for improvement, the singers engage each other, as well as the orchestra, with vigor and skill, making for a satisfying Snegurochka in Russian.

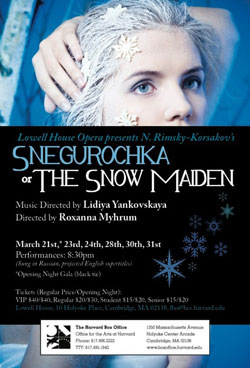

Snegurochka (The Snow Maiden) by N. Rimsky-Korsakov. Directed by Roxanna Myhrum. Music directed by Lidiya Yankovskaya. Presented by Lowell House Opera at Lowell House, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, through March 31.

By Melanie O’Neil

Two days ago, Lowell House Opera premiered a fully-staged production—the first by an American company—of N. Rimsky-Korsakov’s Snegurochka (The Snow Maiden) in its original language: Russian. Russian opera is somewhat of a scarcity in the Boston area for many reasons, the foremost being that it is quite a mouthful for non-native speakers; despite this, the Lowell House Opera presentation generally deals with these difficulties successfully.

Lidiya Yankovskaya leads the orchestra with swift, agile motions that make the tempo clear for the singers in ways that do not diminish the dynamic intensity of the musicians. The chorus, too, rises to the occasion and provides a rustic flair that conveys the nuances of Russian folk music.

Sara Bielanski, as the playful Spring Beauty, Snegurochka’s mother, opens the opera. Although Harvard University’s Lowell Hall is not an ideal opera stage, Bielanski’s bright voice rings clear throughout the hall. She is joined shortly afterward by bass Jeramie Hammond in the role of Frost, whose rich voice sounds very natural in the Russian style and language.

Bielanski, who makes a reprisal in the fourth act when Snegurochka begs her for the capacity to love, delivers some of the most mystifying and beautiful lines of the production. When she explains the sensations of love to Snegurochka, Bielanski proves that her smooth voice can be a versatile instrument. Making use of a melancholic undertone, Bielanski skillfully shapes the lush phrases and drives them forward with a pulsating passion.

Snegurochka, the daughter of Frost and Spring Beauty, is a thoroughly unsympathetic title character. Irina Petrik sings the role with an exceptionally powerful voice that contains a metallic edge. This cold tinge makes her sound a perfect expression of the character’s icy beauty.

Petrik gives Snegurochka all the naivety of youth, but Snegurochka’s lack of sympathy for her friend Kupava’s suffering (for which her beauty is the cause) and selfish desire to feel love makes the figure off-putting—her final demise is relatively unmoving. Snegurochka seems, from the start of the opera, to be excited only by the attention of the shepherd Lel. Her subsequent profession of love to Kupava’s ex-lover, Mizgir, suggests that her search for love is selfish rather than a need to genuinely care for another person. Despite this, Petrik delivers her final aria with a sweet and delicate inflection that manages to show that the character has matured, at least a bit.

Soprano Knarik Nerkararyan in the role of the spurned Kupava and Christine Duncan in the role of the shepherd Lel are the real protagonists of the opera. Both their voices and characters exude a warmth that the ever-jealous Snegurochka cannot manage. Kupava, after being abandoned by her lover, Mizgir, wins our hearts, as well as the sympathy of the Tsar, with startling pleas that boil over with love and rage. Nerkararyan sings Kupava’s passionately lyrical lines with burning indignation and bitter sorrow.

Seeing Kupava’s trusting heart so shamelessly broken makes Lel’s decision to redeem her dignity with a kiss before the Tsar all the more heartwarming. With a velvety voice that coos Lel’s rustic shepherd songs, Duncan brought a vocal dexterity to the part that captures the charming village favorite perfectly; visually, given the role’s call for cross-dressing, the performer was less convincing, often too effeminate to pull off the macho charade.

Lel, who inspired such excruciating jealously in Snegurochka’s cold heart, does not win her in the end but the shameless Mizgir instead. Kevin Kees sings the role of the wealthy Mizgir, who, after laying eyes on Snegurochka, abandons Kupava. Kees’s baritone voice is strong and fittingly dark with a unique vibrato that infuses a compelling urgency into Mizgir’s ardor. Kees’s Mizgir pursues Snegurochka with such a persistent and deranged mania that his suicide after her death comes off as plausible.

The production’s set was routine, but the traditional costumes and lighting effects, although simple, provide striking support. The lighting highlights the loving warmth of the sun while also accenting the sparkles of the bleak, icy heart of Snegurochka. The down-to-earth costumes evoked the a plain, pastoral community.

Several singers in smaller roles sang with awkwardly accented Russian or did not have a fitting voice-type for Russian Romantic music. Although there is room for improvement, the singers engage each other, as well as the orchestra, with vigor and skill, making for a satisfying Snegurochka in Russian.

Tagged: harvard-university, Lidiya Yankovskaya, Lowell House Opera, Snegurochka