Dance Review: “Story/Time” — A Serving of Meta from Bill T. Jones

By Debra Cash

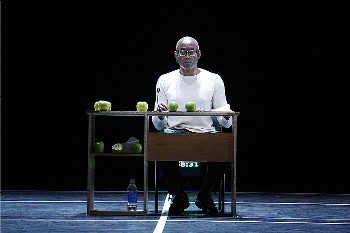

Literally seating himself under a spotlight at the center of the stage, celebrated choreographer Bill T. Jones indulged in a celebrity interview with himself, sharing moving and mundane autobiographical anecdotes while his company danced in abstract arrangements around his desk for exactly 70 minutes.

Story/Time by Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company. Presented by FirstWorks, at The Vets, Providence, Rhode Island, March 10.

Can Bill T. Jones have it both ways?

Jones is the rare American artist who has managed to keep apparent opposites in exquisite balance. The sharecropper’s son is draped with the medallion of a Kennedy Center Honor; a man celebrated for his physical acuity and beauty is ranked as a leading public intellectual; the toast of commercial Broadway (Spring Awakening, Fela!) maintains his oppositional cred.

A little over a year ago, he even merged his creator-led company with one of New York’s beleaguered community institutions, Dance Theatre Workshop, renaming this hybrid New York Live Arts.

In his new, stripped-down work Story/Time, presented in Providence, RI, for a single performance on March 10 as part of a special, three-day company residency, Jones also managed—just—to balance the tensions of today’s cultural métier. Literally seating himself under a spotlight at the center of the stage, he indulged in a celebrity interview with himself, sharing moving and mundane autobiographical anecdotes while his company danced in abstract arrangements around his desk for exactly 70 minutes. Oh, and he framed what he called a “low–key non-popular performance art mode” of a star turn by invoking the “provocation and comfort” of John Cage’s postmodern instruction book.

Quite a gig if you can pull it off.

Bill T. Jones just about did.

In 1958 John Cage created the format of reading aloud a series of one-minute stories whose sequence would be decided at show time by a throw of the I-Ching or dice. In this season of the final dissolution of Merce Cunningham’s dance company, founded with Cage as its chief collaborator, theorist, and cheerleader, Jones’ tribute to what he has called these “bad ass artist types” was nothing if not timely. “Indeterminacy,” with its habit-busting instructions, still offers a refreshing playbook for artists who want to challenge audiences and themselves.

Cage’s contribution, of course, has been mined for a half-century. Chance sequencing is no longer surprising; using text alongside the dancing is no longer unexpected. Jones has been using the latter for years. For Story/Time, Jones and 12 dancers rummaged through a pile of resources. The text was drawn from something resembling a verbal scrapbook of 150 stories, at turns impressionistic, tedious, preachy, and penetrating. Highbrow name-dropping (meals with Jasper Johns, a discussion with Virgil Thompson) and international locales (Amsterdam, Japan) jostled with memories of his parents and siblings and their kids; images of a solitary country boy afraid of snakes became skewed with references to gallery hopping and rides in limousines. This, indeed, has been Jones’s remarkable trajectory. He has earned it.

Jones’s storytelling was framed by dancing drawn from 105 minutes of available choreography. For much of the program, even the most inventive movement sequences and limpid performances were reduced to a decorative border. I recognized episodes where a massed group lifted an individual, garland-like hand holds, and the loose, rebounding leap that a dancer like Paul Matteson performs so beautifully from other Jones’s pieces, but I didn’t mind. They seemed to resonate like memories instead of seeming merely recycled.

Dancers sat on a sofa, perhaps evoking the living room of Jones’s parents, Estella and Gus, and one balanced on its arm, her leg up in arabesque. As per the one-minute rule, there were starts and stops, except when, almost illicitly, the movement seemed to spill over that limit. Sometimes a screen was pulled across the stage, blunting visibility. Shadows loomed, haze set the sofa afire, naked dancers were made modest by gloom. The dancers of the Jones/Zane troupe, almost all of whom have been prominently featured in his recent cycle about the life of Abraham Lincoln, were splendid.

Surprisingly for a work that paid tribute to Cage, Ted Coffey’s ambient sound score held little interest on its own. Low electronics and bells mixed with ambient noises were thrown from the sides and back of the theater in clouds that pulsed around Jones’s rolling, professorial baritone.

As in Cunningham’s work, the touch points between story and dance offered the delights of serendipity. The question of course—Cage’s questions and now Jones’s—is how many channels of perception one human being can attend to at once. What does that do to detail, to the shape of an overall experience, and do we just have to chalk up frustration to the cost of doing business?

In Story/Time, Jones showed his post-modern cards as if he were teaching graduate seminar on perception according to America’s post-modernists. “Questions about the difference between listening and hearing are germane to this work,” Jones explained in one segment. “Questions about the difference between looking and listening are germane to this work. Questions about the difference between feeling and remembering are germane to this work. Questions about the difference between observing and understanding are germane to this work.” And so they are, as were less-spoken about polarities between how familiar speech, especially when tethered to curiosity about a famous man’s life, overwhelms the communicative power of abstract movement. No contest. A talking celebrity wins.

Debra Cash is a Founding Contributing Editor of The Arts Fuse.