Theater Interview: “Deported/ a dream play” – A Tale of New England With Global Implications

Many countries, including our own, still have not officially acknowledged that this genocide actually occurred and who was responsible. New England, and specifically the greater Boston area, has one of the largest Armenian populations in the nation.

Deported/a dream play by Joyce Van Dyke. Directed by Judy Braha. Presented by the Boston Playwrights’ Theatre in association with Suffolk University at the Modern Theatre at Suffolk University, Boston, MA, through April 1.

By Bill Marx

Artists often playfully combine history and dream. James Joyce famously opined that “history is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.” So dramatist Joyce Van Dyke’s choice to infuse dreams and dance (choreographed by Apo Ashjian of Sayat Nova Dance Company) into Deported/a dream play, her meditation on the 1915 Turkish massacre of Armenians and its psychological/spiritual impact on the event’s survivors, makes imaginative sense.

Van Dyke’s approach is also a part of a theatrical tradition in which the surreal comments on the real—August Strindberg’s A Dream Play is an an epic example. By tapping the unconscious, the playwright hopes to move away from simply scoring easy didactic points and confront the deeper divides and resonances set off by catastrophe.

I sent a few questions via e-mail about Deported/a dream play‘s form and message to director Judy Braha and playwright Joyce Van Dyke.

Arts Fuse: What is the importance of staging Deported/ a dream play in Boston now?

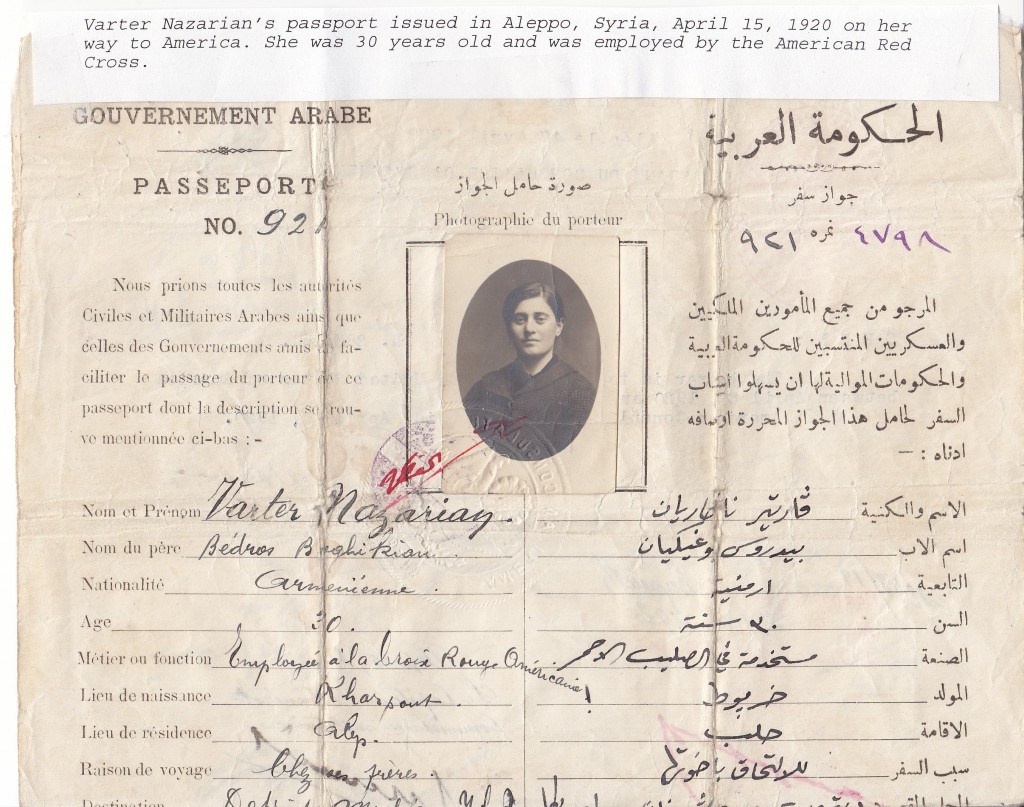

Judy Braha: 2015 will be the centenary of the Armenian genocide. Many countries, including our own, still have not officially acknowledged that this genocide actually occurred and who was responsible. New England, and specifically the greater Boston area, has one of the largest Armenian populations in the nation. Our two central characters, Victoria (based on Joyce’s Grandmother) and Varter (based on Dr. Martin Deranian’s mother) lived in Providence and Worcester respectively when they immigrated to the U.S. This is a local story with global implications. It feels very timely to tell this story that could never be told by these two women during their lifetimes.

AF: Why did you make the decision to make Deported/a dream play a combination of dream and history? When I think of “dream play” Strindberg immediately comes to mind—drama as a spiritual allegory.

Joyce Van Dyke: Excellent question. I was definitely thinking of Strindberg’s A Dream Play, which I love. To me, the surreal has always seemed a higher reality. And dreams felt like the right medium for composing this play from the very start. Dreams allowed me to crystallize and condense a complicated history in haunting visual images onstage. Could I have written this as a “realistic” play? I don’t think so.

But I also want to declare that the dream-world of this play IS real! What these characters experienced in life was beyond surreal—the destruction and transformation of a whole world. How could I be true to the enormity and confusion of their emotional and psychological experience, and to the way it exploded space and time, without using dreams to evoke that reality? Dreams capture the mystery, confusion, and emotional complexity of our lives—and particularly for these characters for whom (as the main character Victoria says) “too much has happened.”

But at the same time, as you say, the play is also made out of history. I wanted to be faithful both to the surreal experience and to the documented personal history of these characters’ lives. Real names are used, real people, real events, real incidents, real statements that people made in life. But that can be true of our dreams too, right?

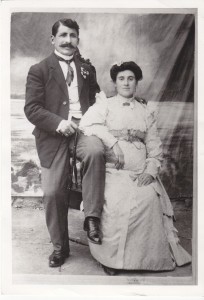

Elmas Boyajian (Joyce Van Dyke’s grandmother, called Victoria in DEPORTED) with her husband Harry (Haroutoun), who is the playwright’s grandfather, and daughter Rose, Providence. All three are characters in DEPORTED.

AF: You have been working on this play for years—what have been the major challenges? Has the integration of autobiographical material helped or hindered the process?

Van Dyke: I felt an obligation to the historical record, far more than with any other play I’ve written. I’ve never written a play based on my own family or on historical events that I’ve been in some ways a witness to (not the genocide itself, of course, but the aftermath for these survivors). Because I only possess tiny fragments of these people’s stories, those fragments felt all the more precious to me. I felt a pressure to integrate those elements into the play as much as possible—and this led to many struggles with the structure and the storytelling of the piece.

The play started out as a very sprawly thing. I had to pare away a lot that I’d hoped to include, for the sake of the whole. For me that always happens with a play, and normally it’s exhilarating to cut, I love to cut—but in this case, it was painful to cut certain stories, details, characters. But the design of the whole has to take precedence.

AF: What are some of the staging problems presented by this approach, which jumps from realism to surrealism? Aging characters on stage from middle age to well over a hundred is tricky, as is including meta-theatrical episodes.

Braha: All of the above and more! The play leaps from the intimate to the epic, and it leaps quickly. Dreams tumble out of Victoria’s imagination in multiple layers and leave as fast as they arrived. In addition, we are jumping in 40 year increments forward, aging, and getting younger. We also have seven actors playing 21 characters with many quick changes. One of our greatest challenges was arriving at a scenic design that could easily, almost magically, shift from an attic in 1938 to a garden in LA in 1978 to a dream space in the future.

AF: How political is this play? In the prefatory statement to the play, you write that “today, although there have been recent hopeful changes as a result of courageous individual and social initiatives, the Armenian genocide is still denied by Turkey, even as the 100th anniversary approaches in 2015.” Is the play a response to this denial?

Van Dyke: The play deals with a very hot political issue with many political ramifications as well as emotional and psychic ones. I certainly see it as a response to censorship—but not just to Turkey’s repression of this history. The censorship has been far more pervasive than that. Many Armenians have not felt able to speak about their own history, for complex cultural, historical and psychic reasons. The characters in the play have never told their own stories—that was true of their real-life originals, and it was a frequent response to the genocide among Armenian survivors.

As Jack Danielian, Dean of The American Institute for Psychoanalysis, has described in his article, “A Century of Silence,” there has been internal psychic repression of this trauma by many Armenians—in addition to overt political repression and widespread ignorance of this history in the general public. I have felt censored myself. For a long time, I didn’t feel able or willing to write this story. The sense of release is enormous.

AF: Would you agree that a key line in the play is “Chaos. You walk on it”? If not, what line would you pick?

Van Dyke: Good choice! For me that line captures the sense of disorientation of these characters, as well as the need to go on. I’m from California, the land of earthquakes. There’s nowhere to flee from an earthquake—it’s everywhere underneath you. You are floating on top of it. And you have to keep going, you have to keep your balance somehow. That was the sense I had about these survivors.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.