Book Review and Interview: “The Lost History of 1914” — Almost the War That Wasn’t

In his exploration of history, Jack Beatty suggests that World War I, as we know it, was an improbable event.

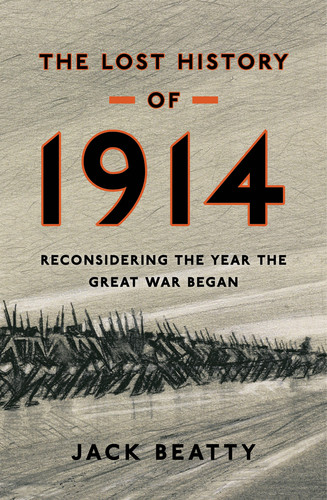

The Lost History of 1914: The Year the Great War Began by Jack Beatty. Walker & Company, 392 pages, $30.

By Harvey Blume

For Jack Beatty, born in the last year of World War II, World War I was, far more than for most Boomers, a family story. Beatty was “raised on tales” of his father’s service in the First World War. The elder Beatty survived a German submarine attack on the U.S.S. Mt. Vernon —- we see him and other survivors in a photographic front piece to the book —- and having declined the disability compensation that was his due, later, during the Great Depression, when compelled to bed down in his car outside WPA work sites, cursed “himself for a fool for passing up the money.”

Beatty is author of The Rascal King: The Life and Times of James Michael Curley, 1874-1958, among other books. He’s a senior editor at Atlantic Monthly and a longtime analyst for NPR’s On Point. Those who know him from the radio venue will not find great disparity between the passion of the spoken and the written voice, except to the degree that on the page he can allow for more scope and complexity.

The Lost History of 1914 entails many histories, many contingencies dissolving into further contingencies — in short, many plausible “what-ifs”. Beatty doesn’t much use the word “determinist” in this volume, but this is an utterly anti-determinist book. If you think history always has to happen as it does —- and World War I has been taught as a test case for this view — think twice. Beatty’s argument is that there were all sorts of ways in which World War I might not have happened, or might not have in the way it did —- and might not, therefore, have amounted to what George Kennan called the “seminal catastrophe” of the twentieth-century. Beatty suggests that World War I, as we know it, was an improbable event, which doesn’t prevent it from being, simultaneously, the worst possible of all outcomes, both because of the immense suffering it caused, and because that suffering could not but make the still greater horrors of World War II much more probable.

For example, the children who survived the Allied blockade of Germany during World War I flocked to the Nazi Party two decades later. The traditional view has been that the Nazis prevailed among German youth because of costumery, uniforms —- hot black leather. (See, for example, Susan Sontag on that aesthetic in her essay, “Fascinating Fascism”). Beatty proposes something different, namely that whatever the allure of boots and jackets, it was more the need to feel protected and fed that the Nazi Party fulfilled, it was the desire for family. As Beatty puts it: “The Allies would not have won the war without starving the German people. . . But victory through hunger, followed by peace through vengeance came at a terrible price.”

He quotes from Ernst Glaser’s novel, Class of 1902: “Hunger destroyed our solidarity. . . Soon a looted ham thrilled us more than the fall of Bucharest.” Beatty adds: “Nothing so tore the mask of righteousness off the face of the Allies as the months of suffering inflicted on the German people between the Armistice on November 11, 1918, and the signing of the treaty on June 28, 1919.” The Allies kept the blockade in place during those months of negotiation. Starvation was, for Germans, the first taste of reparations.

The Lost History of 1914 is a work of far-reaching scholarship. It entails narratives and counter-narratives for all the major powers —- England, France, Germany, Russia, and the United States. The ironies of history grin through the account.

For example, if we were taught about the origins of World War I, we were likely taught that the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand was a fuse primed to detonate world war. Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, not long after to be vacated by the aged, ailing Francis Joseph, was assassinated in Sarajevo by a Serb, which impelled Austria-Hungary to mobilize against Serbia, Russia to mobilize in defense of fellow Slavs, Germany to declare in favor of Austria-Hungary, England and France to weigh in on the side of Russia —- all as dictated by ententes and alliances. But Beatty shows the chain of causation, far from ironclad, can bear comparison to the rickety workings of a Rube Goldberg contraption.

Franz Ferdinand was in Sarajevo to commemorate his marriage to Sophie, the recently minted Duchess of Hohenberg. Sarajevo was the preferred venue because in Vienna, Ferdinand and Sophie were subject to slights and affronts prepared by minions of the Emperor, who detested them both. It was a contingency of the calendar: had Ferdinand and Sophie not been motoring through Sarajevo that day, they would not have been targets for Gavril Princip, who in any case nearly botched the assassination. This irony bites particularly deep: Ferdinand had established himself as the great peacenik of Austria-Hungary, having steered it away from war in several crises. Had he lived to become Emperor of Austria-Hungary, World War I might be the war that wasn’t.

This is not to say the conflict was a random occurrence. A central theme in The Lost History of 1914 is that the elites of Europe feared democratic and/or nationalist stirrings among their subjects as much, perhaps, as they feared each other. The rulers felt the urge, as one historian put it, to “escape forward” from domestic turmoil into war.

The Lost History of 1914 will leave its mark on how we think about World War I and perhaps, beyond that, on how we think about history and history in the making. I welcomed the chance to talk to Jack Beatty about the book.

Arts Fuse: What made you set about writing this book?

Jack Beatty: I had always read about the war. I discovered there was a whole other look at it, suddenly available in a way it hadn’t been. Historians were talking not about an inevitable but more like an improbable war. What had seemed settled was not settled at all.

Then, I’m reading The Strange Death of Liberal England by George Dangerfield. He uses the image of the war as an avalanche that covered everything else in 1914. He said the Ulster crisis [the increasingly violent conflict between Protestants and Catholics in Ireland and between Ireland and England] was underneath that avalanche. I wondered: what else was beneath it?

And in the late ’90s, Niall Ferguson had a book about the war, in which he stated that if the British weren’t able to land what Kaiser Wilhelm called its “contemptible little army”, the Germans would have won the battle of the Marne, and that would have been that. Germany would have won, and Hitler, in that case, would have ended his days as a housepainter.

I started to put things together. The crisis in Ulster almost kept England from entering the war. I went from there to look at the other countries.

AF: World War I always seemed like a proof of a deterministic view of history, don’t you think?

Beatty: It was an exam question: name the causes of World War I and be sure you take plenty of space.

AF: A proof of inevitability.

Beatty: That, I discovered, was an induced perspective. There’s a wonderful paper by Holger Herwig in which he talks about how, during the Weimar Republic, Germans made every effort to portray the war as inevitable. Nothing could have stopped it. This was another way of saying whatever happened, Germans didn’t do it!

Their motive wasn’t to take the Kaiser off the hook. It was to take themselves off the hook, the war guilt hook.

AF: So it was an argument against reparations.

Beatty: Right. The Weimar Germans published a hundred volumes before anybody else. They early on muddied the water. Here, where the war was in such disfavor in any case, American historians seized on the German view, and swallowed it: yes, it was like a force of nature.

That view lasted up until the 1960s. You can see it in Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August where she quotes Lloyd George saying, we slithered over the brink, nobody wanted it, it was a storm. That was 1962. In 1967 we get the first of Fritz Fischer’s two 900-page volumes [published here as Germany’s Aims in the First World War], which change the narrative. Fischer maintained Berlin did want it. Germany wanted lebensraum.

AF: A precursor of what Hitler wanted.

Beatty: Exactly. That’s one of the statements Fischer made. If you look at the map, the land they wanted in World War I was pretty much what Hitler went after later.

The West German government made every effort to run Fischer down, to prevent American universities from bringing him over. But he changed the terms of debate for academic historians, though that hasn’t quite got into the general picture.

AF: Hasn’t ruffled the high school curriculum?

Beatty: Absolutely not.

AF: You mention Niall Ferguson, and his argument for a counterfactual, anti-determinist approach to history. But Ferguson also argues that it’s not empires that create the great catastrophes of suffering and ethnic murder but the dissolution of empires.

Beatty: Well, that’s ridiculous!

AF: Whatever else it was, wasn’t World War I a battle among empires?

Beatty: Indeed. I show, in my French chapter, how the diplomacy of imperialism, which was a zero sum diplomacy -— Europeans dictating terms to conquered colonial subjects —-crept back into Europe, infected it, set the condition for ultimatums and all the rest.

AF: Wouldn’t you say a central theme of the book is that the elites of the countries that fought saw movements toward democracy as movements toward revolution, and preferred war to that kind of unrest?

Beatty: Certainly true with the Germans. That’s the allegation made in a book by Hans Wehler, who wrote that the elites were determined to “escape forward” into war.

What also looms up is the fear of Russia, and what Germans felt as the necessity of a preventive war before Russia was fully prepared. Russophobia helped split the German socialist party. The Tsar was the reactionary. They saw Germany as a beachhead of democracy that would be wiped off the face of the earth when the Cossacks rode in.

But you can see the fear of uprising in my chapter about Mexico and what European leaders thought about what Woodrow Wilson was doing there.

AF: That’s a fascinating piece of history. The U.S. gets involved in World War I partly because Woodrow Wilson got embroiled in Mexico after initially siding with Pancho Villa. You describe that as “the only time in the twentieth century that the United States supported a poor people’s revolution in Latin America.”

Beatty: The European powers couldn’t fathom Wilson. They wanted him to know that what was happening in Mexico represented a threat to their economic interests in Mexico and, beyond that, a revolutionary threat to their empires. Here was a brown-skinned people rising up! They were petrified, the foreign offices of England and the other powers.

AF: You describe the German telegram, the Zimmerman telegram, that winds up in Wilson’s hands. This is after Wilson has sent troops into Mexico to root out Villa, and fails. The Germans, as per that telegram, conclude “The United States . . . lacks all . . . instruments of modern warfare.” The Kaiser decides it’s safe to loose all out war on the American shipping that was England’s lifeline.

But who supports the war?

Beatty: The same pattern applies here as in Europe. It’s intellectuals again, writers, e.g. the New Republic, John Dewey, who support the war. Dewey writes the war is a plastic moment, we can effect history, when we win the war we’ll win the peace, create a new international order.

AF: That’s what’s called Wilsonianism, yes? Wilsonian idealism?

Beatty: Yes, and they got behind body and soul, the progressives. The same happened in other capitals. It was the writers, the chattering classes, that wanted the war. They saw things in abstract terms, which is not how history unfolds.

AF: You quote the political scientist Richard Ned Lebo who looks at twenty-six international crises between 1898 and 1967 and concludes: “These case histories suggest the pessimistic hypothesis that those policy makers with the greatest need to learn from external reality appear the least likely to do so.” That’s bad news.

Beatty: Certainly bad news.

AF: Anything different now?

Beatty: Nothing has changed. It’s because of the tunnel vision, the way they narrow down on the options, and just offstage, the political fears.

Add in the cynicism. Helmut Molke, the German chief of staff, knew that Germany probably couldn’t win, that the war was hopeless, there would be no quick decision. Yet he told the politicians no worries, we’ll get this over with fast. The cynicism is criminal.

Well, we could have avoided WWI, and I wish we had. I have begun to imagine different outcomes for different events. Recently, I wondered about the Alamo— If Santa Ana had given more generous terms to the Texans, some sort of surrender with honor—I wish he had done that, but I’m sitting here in Los Angeles and I might be saluting the Mexican flag if things had worked out differently.

> Well, we could have avoided WWI and I wish we had.

Be a better twentieth century, for sure.

> I have begun to imagine different outcomes for different events.

To be unable to think “counterfactually” is considered a sign of very bad mental health. The term does spill over into psychology. Whether or not we have “free will” to think we don’t is psychotic, to think actions are dictated by voices etc. . .

> I’m sitting here in Los Angeles and I might be saluting the Mexican flag if things had worked out differently.

Woodrow Wilson makes a speech early on apologizing for the ill-gotten gains of the war with mexico,and promising the United States would never do such a thing again.