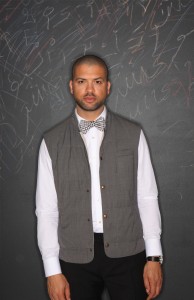

Jazz Feature: Pianist Jason Moran Repays It Forward

By J. R. Carroll

From James P. Johnson to Thelonious Monk to Jason Moran, inspired mentors carry the past into the future.

“[In 1946, Monk] got tired of waiting for gigs to come his way and decided to organize a rehearsal band made up of some younger, adventurous musicians. He created something akin to a collective, not unlike what pianist Sun Ra would establish in Chicago a few years later, or the kinds of collectives jazz musicians would develop across the country in the 1960s. . . . Within weeks the group collapsed . . . [but w]hile Monk’s proposal failed to produce a working band, it set a precedent that would come to define Thelonious’s role in the jazz world for the rest of his life. He became a teacher.” — Robin D. G. Kelley

“Several of these men—most notably saxophonist Sonny Rollins—have shared my belief that Thelonious was in reality one of the great teachers, even though he undoubtedly never gave a formal lesson in his life. . . . [Sonny] recalled his late ’60s retirement of sorts, involving some time in India. ‘When I . . . found out what a real guru was—how they were treated and what they represented—I realized that Monk was my guru.'” — Orrin Keepnews, “Thelonious Monk: A Remembrance,” Keyboard, July 1982

While Jason Moran’s recent Boston presentation of his multimedia contemplation of Thelonious Monk, In My Mind, was an extraordinary evening (a review will be forthcoming soon), this event was the culmination of a week’s residency and part of an ongoing pedagogical relationship with the New England Conservatory.

On the Tuesday preceding In My Mind, Moran conducted a solo piano master class with four advanced students. I had the privilege to observe a remarkable teacher in action and to ponder his own debt to the example of the “piano professor” he came to town to honor.

“Simon Wolf was not a jazz musician; he taught Thelonious works by Chopin, Beethoven, Bach, Rachmaninoff, Liszt, and Mozart. Thelonious developed an affinity for Chopin and Rachmaninoff, and he loved to work through some of the most difficult pieces. Wolf was amazed by how quickly Thelonious mastered many pieces, not to mention his curiosity about the piano’s mechanics and his wide range of musical interests. . . . What Wolf could not teach him, Thelonious learned from the many jazz musicians who lived in the neighborhood. . . . The local jazz musician who had the greatest impact on Thelonious’s early development, however, was a diminutive black woman named Alberta Simmons. She appears in no jazz dictionary or encyclopedia, and she never recorded. But for a good part of her life, she was able to make a living playing ragtime and stride piano.” — Robin D. G. Kelley

“Who do you listen to who’s dead? . . . Most students don’t know of anything pre-bebop. . . . [Y]ou need to listen to pre-1940 players. At the right time they’ll surface and you’ll take what you can. . . . When these masters of the past were around, they were cutting edge.” — Jason Moran

“[M]any of the older stride piano players, James P. Johnson, Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith, Luckey Roberts, Clarence Profit, and the incomparable Art Tatum . . . used to get together at each other’s homes for friendly jam sessions and to share ideas, and apparently [Eddie] Heywood [Jr.] brought Monk along and introduced him around. The time Monk spent among these elder statesmen and their students was as important, if not more important, to his musical development as the time he later spent with the bebop greats.” — Robin D. G. Kelley

“Blues language is important—a fabric that’s always in it. Internal blues may not be the same as what you play. . . . How do you embody the language of the blues? Think about the places the blues come from.” — Jason Moran

“There is a deep grasp of jazz roots and tradition apparent in the blues, ‘Functional’ (listening to the playback, Monk said: ‘I sound like James P. Johnson,’ which is an exaggeration, but an apt one).” — Orrin Keepnews, liner notes to Thelonious Alone, 1957

“Who did you steal from? . . . It’s an issue when your favorite people are haunting your hands. For me it’s Monk and Andrew Hill and a few others [Jaki Byard?]. When you catch yourself doing it, stop playing and think about it. Think about why you like a particular player. When you’ve matured as a player, you put those influences on the side and let them watch what you’ve created.” — Jason Moran

“[Jerry Newman, who recorded Monk on paper discs at Minton’s, recalled:] There was one half-hour version of ‘I Surrender Dear’ that Monk made with tenor saxophonist Herbie Fields that he wore out playing back during intermissions.” — George Hoefer, “Hotbox: Thelonious Monk in the ’40s,” Down Beat, October 25, 1962

“[R]ecord everything: Not just performances, but rehearsals, practice sessions, lessons, even conversations. Listen to the recordings later and analyze them, transcribe them.” — Jason Moran

“A copy of the score [of ‘Monk’s Mood’] found among Mary Lou Williams’s papers provides a fully-elaborated composition with the voicings and left and right hand written out in Monk’s handwriting.” — Robin D. G. Kelley

“[To one student:] There was something about a minute into the performance that was amazing (but then it passed). . . . [To another student:] That was sick! You can make most of what you play be like that. It’s in there; you need to find it. . . . Extract the pieces of the solo you like and work with them. I want to hear you struggle. . . . Think about how your transitioning evolves one way of working with a fragment to a different way.” — Jason Moran

“Perhaps the finest surviving example of Monk playing at home is an eighty-four-minute recording of him working through one tune: Ned Washington and George Bassman’s ‘I’m Getting Sentimental Over You’ . . . The fourth, fifth, and sixth takes, which together add up to a little over an hour of continuous playing, are an exercise in discovery. Monk works through a wide range of improvised figures in a fairly systematic way. He repeats certain phrases, making small rhythmic and tonal alterations each time to see how they sound. Each take is successively more adventurous; while still playing stride piano in tempo, his right hand is more off beat, his lines increasingly angular. . . . He’s listening for different possibilities to construct a tight, ‘edited’ performance”. — Robin D. G. Kelley

“Let all the possibilities arise. . . . Don’t use the first option that comes to mind. Let it go by, let the second option go by. Then, maybe try the third. . . . We’ve got this thing about not being ostracized. . . . When I studied with Muhal Richard Abrams, he said, ‘Nobody’s coming to your house to take your hands off the piano.'” — Jason Moran

“[Randy Weston recalled:] You’re taught to play a piano in a certain way, and if you don’t play it that way, it’s not the correct way. Without saying a word, Monk taught me, ‘Play what you feel although it may not be the way it’s supposed to be.'” — Ira Gitler, “Randy Weston,” Down Beat, February 1964

“What’s your version of the song? Think about the very likely possibility that there are pianists all over the world who are playing [it] at this same moment. . . . A lot of people don’t think that their own feelings are valid input to their playing. . . . Find your own version, based on your own personal history. . . . These songs don’t have destinations. . . . A great performance can change your vision of a song.” — Jason Moran

“[Monk told Steve Lacy] ‘Don’t play all that bullshit, play the melody! Pat your foot and sing the melody in your head, or play off the rhythm of the melody, never mind the so-called chord changes. . . . Don’t pick up from me, I’m accompanying you!'” — Steve Lacy, Foreword to Thomas Fitterling, Thelonious Monk: His Life and Music, (Berkeley: Berkeley Hills Books, 1997); translation of Thelonious Monk: Sein Leben, seine Musik, seine Schallplatten (Waakirchen: Oreos, 1987)

“How do you subdivide? Most players don’t think about rhythm. How can you manipulate rhythm the same ways you manipulate melody and harmony?” — Jason Moran

“I learned more about rhythm when I played with Monk. . . . [It was] a great experience. With Monk, rhythmically, it’s just there, always” — Scott LaFaro quoted by Martin Williams, “Introducing Scott LaFaro,” Jazz Review 3, August 1960

“Sometimes ideas are just about touch, how you articulate your ideas. . . . [Citing Glenn Gould’s early and later recordings of the same pieces:] If you’re thinking about Bach, how many ways can you articulate the same piece? . . . [T]hink of the piano like a computer: Set the inputs and they’ll determine the output.” — Jason Moran

“[Monk’s] eyes light up when he speaks of instrumentalists getting the right ‘sounds’ out of their instruments. He is forever searching for better ‘sounds,’ as he loves to say. He doesn’t seek these effects elsewhere. He creates them.” — Herbie Nichols, “The Jazz Pianist—-Purist,” Rhythm: Music and Theatrical Magazine, July 1946

“We have unsuspecting listeners all the time. . . . What do people expect from music? There’s always a set-up; you can play into or away from the set-up. . . . An uncomfortable way of setting up the music can challenge your [creativity]. — Jason Moran

“You have to be awake all the time. You never know exactly what’s going to happen. Rhythmically, for example, Monk creates such tension that it makes horn players think instead of falling into regular patterns. He may start a phrase from somewhere you don’t expect, and you have to know what to do. And harmonically, he’ll go different ways than you’d anticipate. One thing above all that Monk has taught me is not to be afraid to try anything so long as I feel it.” — John Coltrane quoted by Nat Hentoff, “The Private World of Thelonious Monk,” Esquire, April 1960

“I don’t want total control—-I want to lose control, be as free as I can possibly be in front of people. . . . In a gig, I’ll just walk in and hit “Play” [(sometimes literally)] and be inspired by what comes out.” — Jason Moran

“It took a village to raise Monk: a village populated by formal music teachers, local musicians from the San Juan Hill neighborhood of New York in which he grew up; an itinerant preacher, a range of friends and collaborators who helped facilitate his own musical studies and exploration; and a very large, extended family willing to pitch in and sacrifice a great deal so that Thelonious could pursue a life of uncompromising creativity.” — Robin D. G. Kelley

“The village that makes you—-family, friends, community—-are more important than the people you listen to. . . . Help your people understand the music you like—-and your own music. You have to put your life into your music.” — Jason Moran

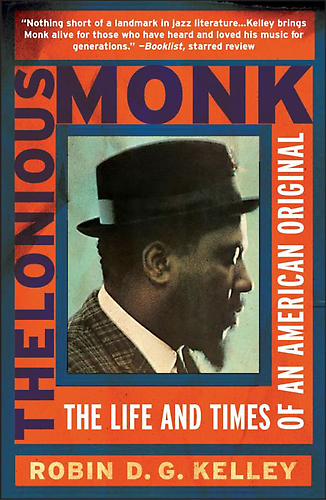

Unless otherwise identified, all the quotes concerning Thelonious Monk are from Robin D. G. Kelley’s definitive and indispensable biography, Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original (New York: Free Press, 2009). All the other quotes are drawn from notes taken during Jason Moran’s recent solo piano master class at the New England Conservatory. (Apologies to Jason for any inaccuracies or infelicitous paraphrases.)