Silent Film Feature: Soviet Masterpiece “Battleship Potemkin” Steams into Town with a New Score

As the Occupy and Tea Party movements attest, this is a time in America of social action and political upheaval—not to the degree that we see in Battleship Potemkin, but significant nonetheless—and this classic silent film has resonance today in that regard.

The Sounds of Silents: Battleship Potemkin. At the Coolidge Corner Theatre, Brookline, MA, December 19.

By Bill Marx

The Coolidge Corner Theatre and Berklee College of Music present a rare screening of Sergei Einstein’s 1925 silent film masterpiece, featuring a newly commissioned, live score composed by professor Sheldon Mirowitz and his students in the Film Scoring Department, under the guidance of department chair Dan Carlin.

This is the third collaboration between the Coolidge and Berklee as part of The Sounds of Silents film series. The Arts Fuse reported on the previous movie in the series, It, starring Clara Bow.

What goes around comes around, including mass protests that could lead to something more. While the Occupy movement points out economic injustice and rule by the 1% in America, thousands of Russian protesters are currently in the streets, marching against a government they accuse of rigging elections and corruption, the police banging heads and harassing journalists. Thus one of the masterpieces of the Soviet film era, Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, steams out of mothballs, buffed up via a restored print and a new score, at a propitious time. Not that that the 1925 film has ever been forgotten, but now, perhaps in a way that the director intended, it serves its purpose as an act of political inspiration, if only as a compelling, cinematic fantasy of uprising, David taking on the Goliath of the Czar.

I spoke to Berklee College of Music professor Sheldon Mirowitz about the challenges of writing music for Battleship Potemkin and if taking the performance to the Kennedy Center in March as part of The Conservatory Project changed his approach in any way.

Arts Fuse: Why Battleship Potemkin now? What does this film have to say today?

Sheldon Mirowitz: Battleship Potemkin is sort of the ultimate social action film. It recounts the rebellion of the Russian battleship—ultimately renamed the POTEMKIN—that came to the rescue of the townspeople of Odessa as they began to organize against the Czar at the beginning of the Russian revolution. As the Occupy and Tea Party movements attest, this is a time in America of social action and political upheaval—not to the degree that we see in film, but significant nonetheless—and I think the film has resonance today in that regard.

It is also an organizing film—the film itself has a social action function, what we used to call propaganda—and I think it can remind us of a sense of relatedness, and obligation, that we in America haven’t felt in the last 50 years. It comes from an earlier, less egocentric, less cynical time but also a time when belonging meant something, and in that way, it can definitely speak to us today with a surprising freshness.

AF: Did you choose to score Battleship Potemkin? Or were you assigned this classic silent film?

Mirowitz: Yes I did—it was one of several recently restored films that we could have done. I remembered a few of the iconic scenes—The Odessa Steps, the mutiny on the ship—and I knew how important the movie was in term of film history, and I thought that it would be great to attempt a score of this scope. Scope, that is, in terms of the music, the size of the story, and the place of the film in the history of cinema.

AF: What are the challenges posed by composing music for Battleship Potemkin?

Mirowitz: Oh my goodness.

First of all, the narrative language of the film is very unusual to the modern American viewer. The story itself is pretty thin—you can say it in three sentences—without any plot twists or complicated narrative events. In fact, there are hardly any characters and none that we follow though the whole film. So the film isn’t really about plot or characters. It’s about big world historical events, in which people and their individual stories swirl together into a Big Story of real, conceptual, and emotional import. So the score really needs to work in that way as well, which is, again, unusual for a contemporary film score. Very different than, say, 2 Fast 2 Furious 2.

Second, however, the film is not so different from 2 Fast 2 Furious 2 in terms of cinematic language. Eisenstein was developing a new way of using cinema, a uniquely cinematic—as opposed to theatrical—way to tell a story. To this end he developed the idea of montage, which uses a non-linear, visually oriented way of circling a story point. This is surprisingly modern, and it very much relies on music to make it work—just as contemporary cinema uses music a la music video form to make its montages work. This of course places a great deal of responsibility on the music—a significant challenge for any composer, not just student ones.

Third, the film is from, and references, a completely different world-view than that of the contemporary, American, film-scoring student or film-going audience. It was very important to get across this very Soviet, socially conscious, broad, but unsentimental point of view. It requires a certain harshness of palette, a kind of “modern” harmony, and a sort of “symphonic” form, that is, again, unusual for most film music.

AF: You have suggested that the score for Battleship Potemkin will be more symphonic than operatic. Could you explain this distinction? Does it divide composing for silent films into two categories?

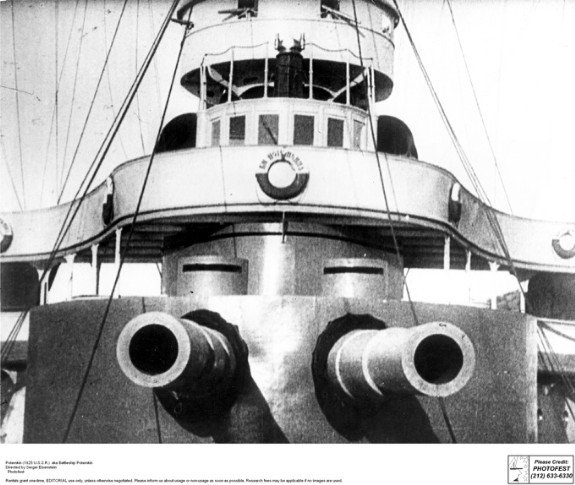

BATTLESHIP POTEMKIN — In terms of cinematic language, think 2 FAST 2 FURIOUS 2, circa 1925. Credit: PHOTOFEST

Mirowitz: It is more “symphonic” in terms of how the musical themes develop. In an opera—and in film in general—musical themes work in a leitmotivic way, meaning that they are attached to characters or events or thematic items in the story. In the case of Battleship Potemkin, themes need to develop and grow as they do in a symphony, spinning out the material so that the story gets shape. In Battleship Potemkin the drama is sort of musical, with movements—there are five chapters to the film—and thematic development in each and through the whole. In the end, there is a kind of climactic orgy of themes as the film itself climaxes with Brotherhood overcoming Duty as the Admiralty joins the Potemkin by refusing to fight. It’s all very thrilling.

But no, it doesn’t divide silent film into two categories. There is montage and there is plot and there is character and each needs to be handled as they individually require.

AF: Will the score pose any particular challenges to the Berklee musicians?

Mirowitz: You bet. The score is a real workout for the percussionist and the brass section. We hope they survive.

AF: Is the score going to reflect the music of the Soviet period? Or are you going provide a more contemporary feel?

Mirowitz: Yes and yes. Both things. There are synths in the orchestra, but the Soviet sturm and drang is definitely part of the mix.

AF: You are taking the performance to the Kennedy Center in March as part of The Conservatory Project. Has this influenced your approach to writing music for the film in any way?

Mirowitz: Nope. We are just extremely excited to bring the show to such a great venue and to show the world outside of Boston what we are doing and how cool it is to see a great, restored, silent film with a great, new score written and played live by terrifically talented, young musicians. We think this a truly unique thing that we are doing, and we are just thrilled to be able to share it with a broader public.

Tagged: Battleship Potemkin, Berklee College of Music, Coolidge Corner Theatre, Sheldon Mirowitz, Sound of Silents, silent film

This looks amazing. Can’t wait to go see it. Great article….I love silent flicks.

in my neo-boshie youth, i saw this movie countless times — & again, more recently. it is the film that still in my opinion most unites absolute propaganda with great art. (a recent book shows how far eisenstein’s heroic potemkin departed from the much more mundane sequence of events).

personally, i think it wd be a mistake for the occupy movement to derive too much inspiration from calls to overthrow the state.

there really is a difference between having a constitution and serving a tsar.

for me, the prokofiev score is inseparable from my feelings about the movie. hearing it with a new score might help me see it in a new way.

Hi Harvey,

What’s the name of the book that provides the facts that inspired the movie?

As for Occupy and Potemkin, I was using “inspire” in a playful way — having an American battleship steam into Boston Harbor in order to assist the protesters would not be of much help to anybody.

i’m not saying the movie was inspired by a book. i’m saying there is a recent book — neal bascomb’s “red mutiny”, if memory serves & there may be others — that tell a much less heroic tale of the mutiny and its outcome. no matter, “potemkin” remains a great movie. but it’s nice to know what really happened.