Movie Feature: Making Music for the “It” Girl

It is really very much of its time and place, its particular moment in history. The social revolution of the 20s, the new freedoms for “modern” women, the flapper phenomenon, and the challenges to the class structure in urban 20th century America are among the issues in this 1927 silent comedy.

By Bill Marx

The last installment in the splendid Coolidge Corner Theater series The Sounds of Silents was the masterpiece Sunrise, featuring a newly commissioned score composed by Professor Sheldon Mirowitz and his class of gifted students in the Berklee Department of Film Scoring, under the guidance of Department Chair Dan Carlin. Those lucky enough to be in the audience were treated to a memorable visual and musical experience—not only F. W. Murnau’s towering expressionist melodrama flickering with stylish fury on a huge screen but an orchestra of determined, young musicians playing a delicate, undulating score with passion and finesse.

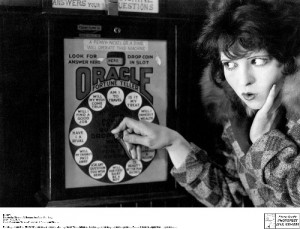

Now on May 2nd at 7 p.m., the Berklee troupe takes on an entirely different cinematic animal—hopping from Janet Gaynor’s demure domestic goddess to the flirty womanliness of superstar Clara Bow in the 1927 silent comedy It, directed by Clarence G. Badger and Josef von Sternberg. In his New Biographical Dictionary of Film, David Thomson posits that Bow was “the first actress intent on arousing sexual excitement who is not ridiculous. She still looks pretty, and her fevered agitation—the fluttering eyes, the restless fingering of men, and teasing angled glances—does seem to speak for the liberated lascivious energies of the new American girl of the twenties.”

I asked composer Sheldon Mirowitz about the challenges of scoring a silent comedy, the sexual appeal of Clara Bow, and the lessons learned by Berklee College of Music students.

Arts Fuse: The last original score from the Berklee College of Music for The Sounds of Silents series at The Coolidge Corner Theatre was for the masterpiece Sunrise. Featuring Clara Bow in her “vamp” persona, It is a very different film. What are the challenges of scoring a sex comedy? In what ways is it easier or harder than a drama such as Sunrise?

Sheldon Mirowitz: Yes, a very different film. Sunrise really deals with big, universal issues of love, loss, fidelity, redemption—and it is very specifically musical in its method and form—Murnau even subtitled the film “a song of two humans.”

It, on the other hand, is really very much of its time and place, its particular moment in history. The social revolution of the 20s, the new freedoms for “modern” women, the flapper phenomenon, the challenges to the class structure in urban 20th century America, etc are the specific issues of the film. Even the “dialogue” (of course, written on cards, not heard) is full of slang and odd idioms of the time. The film is really a comedy of manners, so it was clear from early on that the score would need to reference the time and place as well.

So, first of all, the score needed to at least nod to the swing and jazz of the 20s, where the score for Sunrise did not. That was a bit of a challenge to me and the students as well (their notion of “jazz” is not at all what jazz was at its birth), so I suppose that was hard. The biggest issue, though is that It is a comedy—and comedy is hard. Finding the right kind of funny, how to time the joke, how to not play down to the characters, these are very hard things to do musically. I hope we pulled it off.

By the way, I like to think of it as a romantic comedy not a sex comedy, and in the case of It, it is a comedy about the invention of the modern notions of romance, sexuality, and womanhood. The It of the title is the newly minted (post Freudian) idea of “attractiveness” or “sexiness”—and it is very interesting how different it is from what it has now grown into nearly a century on. Clara Bow is all personality, spunk, and self-assuredness—a very woman-centric idea of attractiveness, not a “sexy” that is defined by the gaze of men but something that the women in the film, and women in the audience, also find appealing on its (or their) own terms. It’s really very very interesting to see how non-physical and how non-coquettish this “sexiness” is.

AF: What is the instrumentation for the score of It? Is there a particular combination of sounds that are good for silent comedy?

Mirowitz: The score is for piano, upright bass, drums (both drum set and orchestral style percussion), clarinet, trumpet, violin, and synthesizer. No, there is no combination of instruments that are good for silent comedy or for silent film in general. I hate the notion that a silent film needs a “kind” of music. Different stories need different kinds of music. Silent films don’t need a particular kind of music any more than black and white films need a particular kind of music or films shot on video need a particular kind of music. The story is what matters, not the medium.

AF: Will the score make playful references to contemporary pop music (Lady Gaga, Madonna)?

Mirowitz: No, though that is a great idea, and I wish i would have thought about it earlier!

AF: In what ways does the scoring for sound films hinder understanding writing and performing music for silent films? Or is it essentially the same process?

Mirowitz: On an important level (see above), it is the same process. On less important issues, it does matter. In a silent film, the responsibility on the music is simply greater. And there is no other help in making the narrative clear, so the music needs to do a bit more to tell the action or to put us in a particular place. At least that’s how I see it. I don’t think that seeing a lot of sound films makes it harder to hear or write music for silent films except to the degree that it creates expectations and prejudices that make it hard for us to accept the film on its own terms—but that sort of applies to everything, not just silent films.

Clara Bow in IT — a comedy about the invention of the modern notions of romance, sexuality, and womanhood. Photo: PHOTOFEST

AF: Has innovative modern scoring for silent films, such as the highly percussive approach of The Alloy Orchestra, influenced your choices?

Mirowitz: It really hasn’t, except to say that I love percussion, I love the Alloy Orchestra, and I’m nervous that they will come and not like our score! Ken came to Sunrise with my friend John Kusiak and was very kind! And I know Roger from a long time ago. Those guys, and of course Caleb, have been interested in finding new voices for the silent films to speak to us today — and they do a great job of it. I am a bit more concerned with just telling the story as effectively and clearly and powerfully (and hopefully as poetically) as we can — and wherever that takes us musically, I’m going to go.

AF: How much room is there for improvisation? Musicians playing with silent films will sometimes react to the mood of the crowd, even provide their own musical jokes.

Mirowitz: I originally thought we would have some, but. no, there is none. We’re composers, we give them the notes to play.

AF: What do the Berklee College of Music students learn about music that they could only learn scoring for, as well as performing with, silent films?

Mirowitz: O my gosh, what a big question. Here are some thoughts: 1) They learn to put on a show! 2) They learn that composing for a film is not just writing a bunch of grooves to fit inside of sound effects. 3) They learn to see the world from the point of view of another very different time, and to still bring to bear on it their own contemporary voice 4) They learn about how intense and exciting it is to do a thing that is basically impossible to do — that is, play a single continuous piece of music that stays in sync with a piece of film for more than 70 minutes, but without any of the technological crutches that we use in film scoring to keep ourselves locked up to the picture.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England