Music Review/Commentary: Awake Between Two Dreams — Steve Lacy’s “Vespers,” Live and Recorded

What the few of us in Jordan Hall heard that night was a richly conceived and beautifully performed song cycle, mostly serious but with some great wit in exactly the right places. It made for a fascinating and enlightening contrast to the CD version of Vespers, which Steve Lacy recorded in 1993.

By Steve Elman

Steve Lacy (1934–2004) left a surfeit of music. Only a handful of modern musicians—Ellington, Miles Davis, Rollins, Coltrane, Bill Evans, Ornette Coleman, and very few others—have lived so fully and left such thorough documentation of their work. In addition, that thing, the kernel of self-definition from which so much great art springs, is there in nearly every piece Lacy wrote. You can hear it: clear, straightforward, and ultimately easy to perceive and appreciate. All his music asks is that a listener set aside his or her preconceptions, put away any distractions, and listen with both ears.

Steve Lacy (1934–2004) left a surfeit of music. Only a handful of modern musicians—Ellington, Miles Davis, Rollins, Coltrane, Bill Evans, Ornette Coleman, and very few others—have lived so fully and left such thorough documentation of their work. In addition, that thing, the kernel of self-definition from which so much great art springs, is there in nearly every piece Lacy wrote. You can hear it: clear, straightforward, and ultimately easy to perceive and appreciate. All his music asks is that a listener set aside his or her preconceptions, put away any distractions, and listen with both ears.

Maybe that’s asking too much.

Music is usually an adjunct activity in our culture—something that accompanies something else—and it’s been so for a long, long time. Because appreciation of Lacy’s music requires attention, and because so many brains just don’t have enough attention to give to it, his work has always been prized by a few and ignored by many.

So, when the New England Conservatory announced a performance of Lacy’s Vespers at Jordan Hall without any big-name soloists and almost no one in the press took any notice, I expected a small house. About 60 people were there on December 8, and from casual conversation overheard, I suspect that a good number of them came as a result of being friends or family of the people on stage.

I eavesdropped on one man trying to explain Lacy to his fellow concertgoers, and I heard many of the things that I now consider misconceptions—things I once thought myself and gradually outgrew: that Lacy’s most accessible work dates from the 50s and 60s, when he was concentrating on playing Monk; that his chief importance in the jazz tradition is as an exponent of the soprano saxophone, primarily because his work on that instrument influenced John Coltrane to pick it up; that he became a relentless avant-garder after he moved to Europe; that his choice of Irene Aebi as his favored vocalist was pretty weird; that his songs with words are incidental sidebars to his “real” music; that his stuff doesn’t have much melody.

Not one of those statements is even close to the truth, and the concert should have disproved most of them to a good listener. What the few of us in Jordan heard that night was a richly conceived and beautifully performed song cycle, mostly serious but with some great wit in exactly the right places. It made for a fascinating and enlightening contrast to the CD version of Vespers, which Lacy recorded in 1993 with his working sextet and two guests, tenor saxophonist Ricky Ford and French horn player Tom Varner, both of whom graduated from NEC. We owe Ken Schaphorst a big round of applause for putting this affair together, and another round to Irene Aebi, Lacy’s widow, who came in from Belgium to assist Schaphorst in shaping the performance and to coach the vocal soloists.

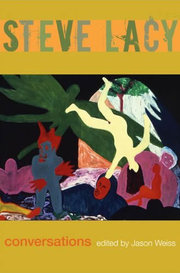

Vespers is based on seven poems by Bulgarian, dissident poet Blaga Dimitrova (1922–2003), who became vice president of her country in 1992 following the fall of its communist government. (She was serving in that role at the time Lacy wrote the cycle.) In a 2006 book of his interviews assembled by Jason Weiss, Lacy describes the poems as “little mystical texts, about life and death, and faith and hope and prayer, and communication.” (Conversations, p. 152).

For example, here is the complete text of the sixth one:

I do not believe

in my disbelief

that my time was awake

between two dreams

that I’ll return to the air

the breath I took from air

that I’ll grasp the moment of death

when my whole life was a moment.

This is not just a collection of seven songs. Lacy has introduced elements that give the cycle an overall unity. Most notably, each piece features one primary soloist, although three of the songs include what might be called secondary solos. This structural concept puts particular weight on each individual in the group to move the music forward when called upon to do so, and there can be no redeeming one lackluster solo with better work later. Each of the seasoned players in the 1993 recording had no problem with the pressure, but there was some perceptible sweat on stage at Jordan.

In the 1993 recording, there are pause-bands between the songs, but there is such a sense of connection between the end of one and the beginning of another that the listener senses the composer’s wish that they should be performed without interruption. This was realized in the Jordan Hall performance perfectly, and the audience cooperated by holding its applause until the end of the cycle.

Lastly, there are two passages of a capella playing in different songs that serve to reinforce one another, at least in the recorded version. In the untitled song dedicated to John Carter, French horn player Tom Varner breaks away from the ensemble for an unaccompanied passage, eventually joined by Steve Potts playing soprano saxophone. After a short joint improvisation, Varner drops out and leaves the music to Potts. In the untitled piece for Stan Getz, Lacy and tenor saxophonist Ricky Ford indulge in an almost identical dance. These two moments provide links between the improv sections, and I was disappointed that both of them were omitted at Jordan Hall.

But this is a song cycle, and the songs are the heart of the work. Vespers provides some outstanding examples of Lacy’s gift for a form he virtually invented. These are art-music settings of poems, but they are certainly not classical in spirit. Most jazz listeners don’t think of them as jazz either. Working with Aebi, who considers herself influenced by such non-jazz precursors as Lotte Lenya and the folksong traditions of her native Switzerland, Lacy crafted a novel, declamatory approach to song, one that admits no variation in rhythm or embellishment of melody but still allows some flexibility in feel and presentation. The proper way to sing these songs is the way that Aebi sings them, trying for a big, mostly vibratoless sound with a horn-like resonance. (“ . . . that mountain voice, that yodel. That was the sound that turned me on.” [Conversations, p. 230]). When sung well, Lacy’s song texts are pure and marvelous experiences, but the untutored listener is going to be surprised by this approach, and he or she has to set aside preconceptions to hear them as they deserve to be heard.

Like almost all of his art songs, each song in this cycle is built in layers. At the core is the text. Lacy describes the process of writing music for words as a process of discovery. “It’s not you that does it—it’s IT that wants to be done.” (Conversations, p. 88). His goal is not to highlight or enrich the text in a mechanical way but rather to decorate it with melodies that spring organically from it.

A second element in the construction of a Lacy composition—vocal or instrumental—is often the dedicatee, usually a person that Lacy admired, an external element that adds a sometimes indefinable resonance within the music. In the case of Vespers, Miles Davis, Stan Getz, Keith Haring, clarinetist John Carter, and the Italian poet Corrado Costa all died within two years of the composition, and they are each remembered with one of the dedications. Dedications to Charles Mingus and artist Arshile Gorky are tossed in for good measure.

Some of the texts relate directly to what we know of the dedicatee in question (Miles gets a poem called “Multidimensional,” for example). In some cases, the music provides a connection to the dedicatee. For example, one of the motifs of “Across,” dedicated to Mingus, is a repeating figure that might have been pulled out of “Peggy’s Blue Skylight.” As another, the untitled text dedicated to Getz is a sort of bossa nova, the Brazilian form that gave Getz his biggest hit records. But sometimes the connection between the song and the dedicatee remains a mystery to the listener—for example, “Unconsummated” forthrightly uses the changes of “Exactly Like You” / “Take the A Train” without being dedicated to Jimmy McHugh (who wrote the former tune) or Billy Strayhorn (who based the latter on it); instead, it’s dedicated to the Italian poet Costa.

The third element—again whether we’re talking about Lacy’s vocal or instrumental music—is the drama of the composition, the individual elements of structure that make Lacy’s work so distinctive for his familiars and occasionally so challenging for new listeners. Even though he writes all kinds of lines, in all shapes and lengths, the way in which each piece unfolds from beginning to end has a powerful logic that balances surprise and reassurance. Lacy came to this approach through his study of the music of Thelonious Monk (which began in the late 1950s and informed his playing intensely for a decade), along with his work in Monk’s group (less than six months of actual performance, but a profound experience in molding his thinking). “What Monk had was the appropriate containers. He wrote the lines that made the guys sound good and that they liked to play. . . improvisation came naturally out of that material . . . That was what I was after.” (Conversations, p. 136). Both composers love “the sound of surprise” and making the music do as much as possible with as few notes as possible. The principal difference between the two is that Monk usually wrote in one of the two most familiar forms of American music—blues form or the 32-bar, AABA, popular-song form—and Lacy rarely used any standard structure.

It may be useful to map out the emotional landscape that each of them paints for a listener and then come back to Vespers.

The first time you hear a Monk line, no matter which of the two forms he’s using, it can be disorienting; that first line of melody often holds an off-balance, rhythmic accent or an unpredictable pause or a hard dissonance—you have to work to keep your musical bearings. Then the line is repeated; now it seems more familiar, easier to get your head around. If Monk is working in AABA form, he then throws you an alternate theme line, maybe just as spiky as the first line but somehow connected. At last, Monk gives you resolution, the return of the first line. And, amazingly, now it sounds familiar, funny, delightful, touching—not odd at all. The solo sections follow, and by the time the melody of the tune returns, it seems like an old friend.

Lacy is not bound by such familiar forms, but repetition is crucial to his work, as is the sense of surprise. He has a strongly linear approach, featuring dramatic (sometimes obsessive) repetitions and sharp tempo contrasts, harmony under the melody lines to provide emotional color, and relatively simple structures for the improvisational sections. His themes do not always return at the end of a tune, but he often provides a rounding off of the performance by retrieving some element that he introduced before the improvisational sections.

Steve Lacy: All his music asks is that a listener set aside his or her preconceptions, put away any distractions, and listen with both ears.

In the case of his vocal music, he also calls on the example of Ellington. “Very, very often, most often, we use a form where the introduction sets up the piece . . . I got that from Duke Ellington in the first place . . . Ellington suggested these formal transitions between a four-bar introduction and a thirty-two bar tune and then a recapitulation and a solo. He put those things together in a superior way” (Conversations, p. 235).

This is the structure of “Multidimensional,” the first song in the cycle:

Soprano saxophone opens for about 40 seconds, without accompaniment or prearranged theme. (Lacy himself played this part in the 1993 recording, and Michael Sachs took the cue for his improvisation in the Jordan Hall performance from Lacy’s lyrical meditation—a mood both wistful and spiritually uplifting.)

The saxophonist leads into the written material by playing a 12-note “fanfare,” which is then repeated twice by the band in harmony. There is a short, tense moment of silence. Then the band plays a jagged series of notes in unison —first four, then three, then two, then one. Then they repeat the same sequence.

The piano plays a single long note, which is passed hand-to-hand through the entire band, from piano to alto sax to arco bass to tenor sax to soprano sax to French horn to a press roll on the snare drum. This note becomes both the singer’s cue and the first note sung.

The song setting follows, using a medium-tempo swing, with the exact same melody repeated 10 times, once for each line of the text. Each line consists of a group of seven notes followed by a group of five notes. Since the lines don’t scan to that rhythm, some words are stretched to fit. Toward the end of the text, the horns come in under the singer.

The world is multidimensional

and that gives us headaches.

We want it to be monochrome

so it can be clear.

We want it to be uniform

so it can be true.

We want it to be limited

so we can grasp it, make it stay.

But its dimensions are endless

the world keeps slipping away.

Then the jagged series comes back for two repetitions of the four-three-two-one pattern, and the rhythm section slips into a relaxed swing for an alto saxophone solo. The harmonic foundation for the solo is an agreeable scale pattern, allowing the soloist to shape his improvisation without concern for chord changes.

In the 1993 recording, tenor saxophonist Ricky Ford picked up a figure from Steve Potts’s alto solo to lead into a light, collective-improv passage that served as a transition to the second song. At Jordan Hall, there was no group improv; the band went directly from the alto solo, played by Andrew Halchak, into the next number.

What’s most important about this structure is the sense of completeness that it provides. When you hear the fanfare, the repetition lets you know it’s a fanfare. When the single note is passed from instrument to instrument, it is as if Lacy is giving each player a chance to nod to the listener. The music under the text is amusingly rigid, considering the content of the poem. The alto solo, with its relaxed structure, relieves the tension that’s been built up, so much so that there’s really no need to return to the opening material—it feels logical to move right into the next tune.

I’ve suggested above that the approach at Jordan Hall was a bit different from the approach in 1993. There were a number of other differences, but nearly all of them served to illustrate the resilience and power of Lacy’s work. They are discussed roughly in the order of importance:

In the recording, Irene Aebi, Lacy’s wife, sings all the songs. At Jordan Hall, four singers were featured, with Aebi on stage as a kind of backup coach. This five-voice choir sang the first song, and it was a shock. I’ve never heard a Lacy piece in which a group of singers attempted to coordinate efforts. It’s not a simple melody, and this is not a simple text—words like “multidimensional” and “monochrome” do not lend themselves to group singing. Inevitably, the texture was a bit muddy, and one needed the printed text to understand the words. Fortunately, all the rest of the texts (with the exception of the John Carter song, sung in duet by David Devoe and Richard Saunders, and the very last lines of the last song, sung by all five voices) were sung by individual soloists.

Inevitably, each of the singers must be compared to Aebi. What was delightful about the performance was that each of them was able to demonstrate some personal aspect of style while still upholding the standard set by Aebi. Each of them deserves a mention:

Of the four, I was least impressed by Neha Jiwrajka, who was featured on “Urgency.” She has a lovely, dark sound and sure pitch but not much support under her notes or projection into the hall. David Devoe, featured on the untitled poem dedicated to Stan Getz, has the most idiosyncratic voice, with a graininess that recalls Dave Frishberg or Michael Franks (but with much better technique)—I was surprised by how well this kind of voice adapted to Lacy’s stuff. Hee Jin Kim, featured on “Urgency,” is a very assured singer with a big voice and an irrepressible sense of swing. But my biggest revelation of the night was the work of Richard Saunders, who was featured in “Across.” Saunders is a high tenor, and his leaps into his upper register were thrilling—beautiful, unforced, clear, well-suited to the material. My ears are not good enough to tell whether he has a particularly smooth falsetto or whether he can actually hit those high notes naturally, but he has a special gift, and I hope he runs with it.

The instrumental performers at Jordan Hall were not the regular Lacy bandmates and veteran guests for whom the original work was written. They were all younger players and inevitably suffer a bit by comparison, but most of them have nothing to be ashamed of. They follow in the footsteps of other NEC players who learned from or played with Lacy during the few years late in his life when he was on the NEC faculty, and one can hope that this experience turns them toward more exploration of Lacy’s music. For one, they can look to baritone saxophonist Josh Sinton, who was so inspired by his work with Lacy at NEC that he formed the band Ideal Bread to explore Lacy tunes in depth.

One has to feel sympathy for Jennifer Hyde, who played the written horn parts with great facility but clearly was out of her depth as a soloist. I felt the contrast more keenly because she was being asked to fill the enormous shoes of Tom Varner, who is one of the few players on the planet who can solo cogently on French horn and whose solo on the recording of the untitled piece for John Carter is a rich and brilliant statement showing strength in every register of a notoriously difficult axe.

Henry Fraser is a promising bassist who should let his music breathe a little. Like many other bass players, he needs to build enough confidence in his intonation to slow down and let the notes sing. He has a good basic sound, but the amplification in his feature (“Across”) added some unfortunate gritty overtones. Fortunately, his solo improved as he went along, and he showed off some clean double-stops and some very pretty chording towards the end. Again, the precedent is hard for Fraser to live up to. Jean-Jacques Avenel, Lacy’s long-time bassist, had the spot on the original recording, and his solo, complete with spot-on harmonics and incredible control of dynamics, would be very hard for any bass player to beat.

Andrew Halchak played the alto solo originally given to Steve Potts on “Multidimensional,” and he had the unenviable task of following the vocal quintet and making the first extended, improvisational statement. I’ve heard him with the NEC Jazz Orchestra, and I know that he is a significant talent. On this night, he seemed a bit tentative and not up to the standard set by Potts, who is a marvelous and underappreciated player.

Michael Sachs had the role no saxophonist would volunteer for—the soprano part played by Lacy on the original recording. He seemed unfazed by the challenge, handling the introductory improv on “Multidimensional” with great sensitivity and then delivering a bright, strong statement on the piece for Stan Getz, showing off some impressive fingerwork.

Evan Allen is a promising pianist, though his outing here could not give a full picture of his talent. His solo on “Urgency” brought out the Asian feel of the music exactly as original pianist Bobby Few did, and then he made his own lyrical statement, brief but well-shaped and precisely to the point.

Panamanian tenor saxophonist Christian Contreras, filling Ricky Ford’s spot on “Unconsummated,” was mightily impressive. He used the thematic material of the song as a jumping-off point, negotiated the a capella section with ease, and capped his solo with a direct quote of “Take the A Train” to help out those who failed to recognize the familiar chords.

Most valuable player? Perhaps this will come as a surprise—the drummer, Robin Baytas. His support through the evening was always tasteful, never self-aggrandizing, and when it came time to solo, introducing “Vespers,” he came up with ideas that John Betsch should have used. The concluding poem in the cycle is sober, almost a cortege, perhaps recalling the very unhappy life of the dedicatee, painter Arshile Gorky, whose final years were a catalog of disappointment and pain ending with his suicide in 1948. In the original recording, Betsch is too busy and not respectful enough of the overall mood. Baytas showed how well he understood the piece, using space very effectively, and even in his faster passages holding on to the feeling of a funeral parade.

The least important matter is still somewhat important. Apparently, four out of seven of the titles of the individual songs were shown improperly on the Vespers CD. Assuming that the NEC program has the titles shown correctly, I’ve provided a concordance in the CD list appended to this post.

Maybe it’s a bit too simple of Lacy to have said that Vespers is about “life and death” and all the rest, but it is no exaggeration to say that his loss hung over the performance of his work at Jordan Hall. Such vital music ought not to have been made by a dead man.

I’ve consoled myself a bit by reading his beautiful and eloquent, off-the-cuff comments in Conversations, a collection of interviews with Lacy and Aebi assembled by Jason Weiss in 2006. If you are a Lacy fan and you don’t own it, you should. The optimism, the humility, the creativity, the greatness of soul—they’re all alive again here. It makes me feel that Lacy chose this text, the third in Vespers, quite deliberately, even as a kind of valediction:

I have no fear of being

trodden down, like grass.

The trampled ground is likeliest

to make a path.

Steve Lacy, Conversations (ed. Jason Weiss) (Durham NC & London: Duke University Press, 2006)

A miscellany of CDs and links related to this post:

Steve Lacy Octet: Vespers (Soul Note, 1993), with Steve Potts, Ricky Ford, Tom Varner, Bobby Few, Jean-Jacques Avenel, John Betsch, and Irene Aebi

(Notes: Some CD versions are produced on demand; these will probably not include a personnel list or the texts of the poems. The titles of the individual songs as shown on the CD do not correspond to the titles shown in the Jordan Hall program. For those who care, here is a concordance:

Proper title:

Multidimensional

Unconsummated

(to John Carter)

Urgency

Across

(to Stan Getz)

VespersTitle as Shown on CD:

Multidimensional

If We Come Close

Grass

Wait for Tomorrow

Across

I Do Not Believe

Vespers

Steve Lacy: Solos Duos Trios: The Complete Remastered Recordings on Black Saint and Soul Note (a 6-CD set of reissues from the Black Saint and Soul Note catalog, at a bargain price, to be released in early 2012; regrettably, it does not contain Vespers)

Steve Lacy Quintet: The Beat Suite (Sunnyside, 2003), with George Lewis, Jean-Jacques Avenel, John Betsch, and Irene Aebi (one of Lacy’s last extended vocal works, a song cycle based on texts by Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, etc.)

Ideal Bread [Josh Sinton, Kirk Knuffke, Reuben Radding, Tomas Fujiwara]: The Ideal Bread (KMB, 2008) (includes “Trickles,” “Esteem,” “Capers,” “Bud’s Brother,” “We Don’t,” “Quirks,” “Kitty Malone,” and “The Uh Uh Uh”)

Ideal Bread: Transmit (Cuneiform, 2010) (includes “As Usual,” “Flakes,” “The Dumps,” “Longing,” “Clichés,” “The Breath” and “Papa’s Midnite Hop”)

Saxophonist Josh Sinton offers short takes on five Lacy performances, including “Unconsummated” aka “If We Come Close” from Vespers, with the complete tracks on demand, produced by WBGO’s Josh Jackson for “Take Five: A Weekly Jazz Sampler”

Ideal Bread’s Myspace page, which includes on-demand-accessible performances of “Unconsummated” aka “If We Come Close,” “Quirks,” “Clichés,” and “The Breath.”

A comparison of a Lacy solo performance of “The Breath” and a group realization of the tune by Ideal Bread, produced by Lars Gotrich (NPR Music).

Christian Contreras’s biography from his website.

David Devoe’s performance of Herbie Hancock’s “One Finger Snap” from his Myspace page.

Andrew Halchak’s biography.

Neha Jiwrajka’s performance of “September in the Rain” from her Myspace page.

Richard Saunders’s performance of “Too Beautiful” from ourstage.com.

Michael Sachs’s website.

— Steve Elman

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

Tagged: Blaga Dimitrova, Ideal Bread, Irene Aebi, Ken Schaphorst, New England Conservatory, Steve Lacy