Film Commentary: The Redemption of Wes Anderson

It’s easy, and popular, to write director Wes Anderson off as a hipster who offers nothing beyond quirk and the occasional funny line. But his films are really American versions of the French New Wave.

by Justin Marble

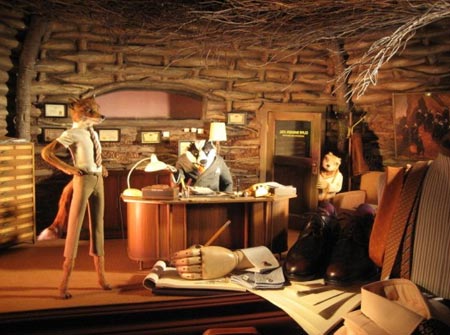

An animal contemplates his redemptive life in Fantastic Mr. Fox

An animal contemplates his redemptive life in Fantastic Mr. Fox“He redeemed himself.”

“Redemption? Sure. But in the end, he’s just another dead rat in a garbage pail behind a Chinese restaurant.”

Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox (At the Somerville Theatre and other area cinemas) may appear on first glance to be just another kids’ movie. But the latter, more than any other of his films, demonstrates Anderson’s obsession with redemption, with rescue, with finding meaning through heroic acts. Its that concern with existential testing that, to my mind, makes his films modern-day, mainstream American successors to films of the French New Wave, where characters in Band of Outsiders and Breathless are similarly obsessed with the nerve and romance of big screen gangsters.

It’s easy, and popular, to write Anderson off as a hipster who offers nothing beyond quirk and the occasional funny line. Beyond that, he always seems to make the same film, where a bunch of caricatures try to figure out how to live with each other (whether they’re a set of brothers, friends, a research team, acquaintances, or a whole family). Perhaps most damning is that Anderson’s characters don’t behave, or speak, like real people. Heck, in his latest film, they actually aren’t real people (he opted for stop-motion animated animals). These criticisms are fair, and true to an extent. But there may be a hard-headed vision behind Anderson’s apparent airheadedness, a value that has been overlooked, perhaps because it is hard for American critics and audiences to appreciate it.

Let’s examine the films of the French New Wave. Almost without question, the films of masters like Jean-Luc Godard or Francois Truffaut are accepted as being some of the greatest of all time. Yet examining the characters in these films, we don’t find real people. They say strange things, they act without motivation — they exude quirk. Even the technique Godard made famous, the jump cut, makes no actual sense. The dialogue continues uninterrupted while the scene changes. All of this is to be expected when you watch a French New Wave film.

But in American cinema the standard for aesthetic success is limited to believability and realism. Even amateur filmgoers will walk out of a theater remarking that a situation was unrealistic, or the dialogue was unbelievable.

Anderson’s films run counter to that prejudice; they feature implausibility in spades. Richie Tenenbaum is a former pro tennis player, in love with his sister to the point of suicide. Steve Zissou is a crazed modern-day explorer looking to get revenge on the jaguar shark who killed his friend. None of these situations have any relevance to real life. It is tempting to see these films as frivolous, but that would be a rush to judgment.

Consider the crux of Fantastic Mr. Fox: the rescue of Fox’s nephew Kristofferson from the hands of the evil Boggis, Bunce, and Bean. Because he has ruined his relationship with his entire community, Mr. Fox opts to stage a daring rescue in an effort to redeem himself in the eyes of his friends and family.

The whole thing is ridiculous — a fox going up against humans, armed with guns? Communicating with paper cups with a wire between them? Sure, these are devices designed to get a laugh or trigger a (parody) of an action sequence. But the prevalence of these rescue scenes (and there is one in almost every Anderson film) and the director’s subsequent exploration of whether our actions ultimately have meaning push him into philosophical territory of the French New Wave.

Of course, this not the first time a rescue has appeared in an Anderson film. For that, you’d have to go all the way back to his first film, Bottle Rocket. The climax of that film involves an unnecessarily elaborate heist of a storage facility, which goes wrong when a gun goes off giving one of the members of the crew (Applejack) a heart attack.

The parallels to the plot of Godard’s Band of Outsiders, where small-time crooks get in over their heads after a big score, are pretty obvious. And while the main character, Dignan, is ultimately a fool who gets played by the much smarter Mr. Henry, he has a sense of honor. Realizing they left Applejack inside, Dignan rushes back in as the police are on their way to save him. Of course, this leads to him being arrested. He may be a thief, or he may want to be a thief, but he is an honorable one.

In almost all of Anderson’s films, there are characters like Dignan, who find ironic meaning through heroic action. Often, they are lost, searching for something. Their redemption, their honor, their romantic heroism offers small comfort.

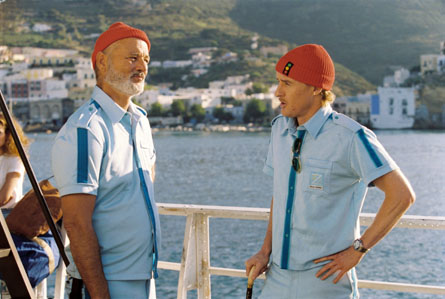

The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou -- the value of family bonds

Besides Fantastic Mr. Fox, the film that best demonstrates this notion is Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou. Steve has thrown himself completely into taking revenge on the jaguar shark that killed his best friend. He is a man on a mission, who will stop at nothing to complete his quest. Again, there is a rescue after the ship is robbed by pirates. Zissou and the crew go after the bad guys, in order to get their money and rescue a “bond company stooge.” The goal does not appear to be that important– what crucial is that action is being taken.

In fact, the “action scenes” here are purposefully ridiculous, much like the French New Wave. Zissou and his team suddenly turn into action stars who can fire infinite numbers of bullets and avoid any danger. Again, the ending to Band of Outsiders comes to mind, where Arthur takes multiple bullets to the chest and still returns fire before dying a big exaggerated, death.

Anderson’s films, like the French New Wave, are ultimately about a search for meaning — none of his characters have figured out how to live with self-respect. And so they are easily taken in by these notions of justice and adventure as their existential calling.

But there is important distinction between the films of the French New Wave and Anderson’s own philosophy. For Godard’s characters, these poetic deaths are all they will find in life. Anderson offers salvation in the form of family and kinship with fellow man (and fox). My opening quotation makes this point: redemption is important, but it only goes so far. Rat’s still a dead rat in a garbage pail in the back of a Chinese restaurant (if there is a modern-day cinematic quote that calls to mind Godard more than this, I haven’t heard it).

Zissou learns this in Life Aquatic. After losing Ned (his supposed son, who it turns out isn’t his son, but they became like father and son anyways), Zissou eventually finds the elusive jaguar shark. But the beauty of the fish makes him realize how little he has to gain from destroying it, so he turns away. Vengeance, heroism, adventure, these will satisfy a man for a time, but they cannot be the ultimate goal. Instead, Zissou has found family in the crew that has helped him.

Anderson references this scene at the end of Fantastic Mr. Fox. On their way home, the band of thieves sees a magnificent wolf. They give him a fist pump, and he returns the favor. That both these encounters involve animals suggests that, for Anderson, the attitude expresses a spiritual and/or biological force. Like Zissou, Fox similarly realizes that he cannot be a thief all his life. Before, he found meaning in his work, which was stealing. Now, he must find it through his relationships with others.

Nearly all of Anderson’s films explore this idea, to the point of obsession. His films are about more than comic eccentricity, they are about what happens when we cannot find meaning as individuals in our lives. Godard’s characters find meager comfort in a big-screen cinematic death; Anderson’s find their reward in relationships, as flawed as they may be.

The pivotal scene in The Darjeeling Limited is another rescue. Even in this meandering film, which revolves around three brothers reconnecting on a trip to India, test, action, and crisis eventually arrive. After the brothers decide to “go their separate ways,” they come across three young boys who have fallen into a river. Each brother attempts to rescue a boy, but Peter is unable to save his against the strong current and rocks.

“I didn’t save mine,” he says, as if preventing this boy’s death was his one charge in life, something he was supposed to do — rather than a random and freak accident. It is as if Peter’s failure has cut him off from redemption and happiness. The brothers then witness the sense of community and family in the Indian village mourning the dead boy. Rather than simply leave each other, the brothers decide their friendship (if not their familial relation) is worth saving after all. Peter can find love and happiness despite his failure. For Anderson, he tried, he took responsibility and attempted to help someone else (in contrast to the brothers’ mother, who abandons her children). Dignan never pulls off the ultimate heist. Zissou never kills the jaguar shark who destroyed his friend.

Results are less important than the fact that actions are motivated by benevolence. They may “fail” in the eyes of the world, but to Anderson, family and friends accept you when you fall short.

The Royal Tenenbaums, which is Anderson’s ultimate ode to family, supports this strength in unity idea. While there is no explicit rescue scene as in these other films (although Royal does rescue his grandchildren from a speeding car, paving the way for a reunion with his son) Tenenbaums ends on a note of family redemption. Early in the film, Royal sees a particularly impressive tombstone, listing the accomplishments of the deceased. “Hell of a damn grave,” he says. “Wish it were mine.” One of the last shots of the film is of Royal’s headstone: “Died tragically rescuing his family from the wreckage of a destroyed sinking battleship.” In a literal sense, this is patently false — in another, it’s completely true, because Royal did rescue his family, he did redeem himself in the end.

Fantastic Mr. Fox -- the dignity of belonging

Ultimately, Anderson believes that our actions do have meaning, but they have meaning because they impact those around us. Stylistically, Anderson’s film have much in common with the French New Wave, but the latter’s characters never find love and acceptance beyond a romantic fling. Anderson’s outlook, though colored by failure, is considerably brighter.

Nearly all of Anderson’s characters are failures in the real world, they develop weird tics and seem immature and unrealistic to others. And this has caused many critics to write Anderson off as a purveyor of alternative “indie” behavior simply for the sake of it. And they have a point: at times, Anderson seems to get lost in the cartoonish worlds he creates, overpopulated by ridiculous characters who defy reality.

But there are always those scenes that snap the film back into something truthful. It doesn’t matter whether Zissou kills the tiger shark, or if Peter saved that little boy, or if Dignan pulls off the heist. It’s the fact that they’re trying, struggling, that makes them real. It is through these actions, and the modest but real effect they have on others, that his characters find salvation and redemption. In the end, we may all just be dead rats “in a garbage pail behind a Chinese restaurant,” but to Anderson our actions have consequence and meaning to the people around us, especially our families.

Tagged: -Jean-Luc-Godard, Fantastic Mr. Fox, Film, French New Wave, Justin Marble

Great article!