Boston Noir: A Grimy Ride Through the Dark Side of Beantown

This enjoyable anthology of crime stories proffers a grimy ride through the murderous and creepy side of Beantown.

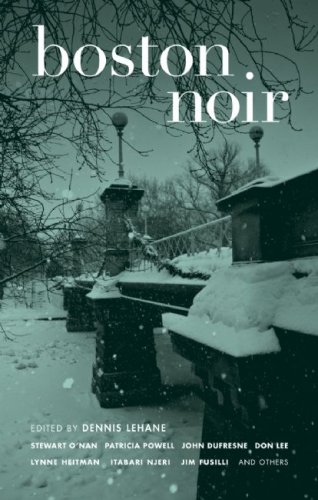

Boston Noir, edited by Dennis Lehane. Akashic Books, $15.95

Boston Noir, edited by Dennis Lehane. Akashic Books, $15.95

Reviewed by Kate Vander Wiede

In the introduction of Boston Noir, editor, contributor. and best-selling novelist Dennis Lehane explains that while Aristotle “mandated that a tragic hero must fall from a great height,” the noir genre generally finds tragedy among working-class men and women who fall from curbs, not mountainsides.

The latest addition to Akashic Books series of ‘noir’ anthologies faithfully follows Lehane’s demand; the best yarns here, though gloomy, touch on the worries we all experience throughout our lives – lack of fulfillment, loneliness, indecision, stagnancy. These gloomy tales bring our own dark fantasies to the forefront. If our livelihood or our happiness was at stake perhaps we too would raise a gun instead of walking away, turn to poison rather than give up something we love. Or perhaps not. We can dream noir dreams, can’t we?

For example, in “Exit Interview,” Lynne Heitman introduces Sloan, a woman executive who kills her boss after being passed up for a promotion. Heitman deftly creates a believable back story for this nine-to-fiver turned manic murderer, who blithely reasons that “she would always be a senior portfolio manager, which was why she’d had no choice but to take the .22 out of her bag and shoot Trevor through the head.”

Don Lee’s “The Oriental Hair Poets” finds an ex-policeman private-investigator missing a chance “to emerge from the deadness.” His inability to trust his love interest leaves the investigator back where he started—alone. Lee explores how easily apathy can become a routine, probing the difficulty of breaking a comfortable but self-destructive cycle.

In editor Dennis Lehane’s contribution, a guy named Bob faces losing the one thing that brings him happiness: his new puppy. Having lived an unsuccessful and lonely life, Bob explains the stuff that haunts him (“the shitty things you did to get ahead. Those things laughed at you if your ambitions failed to amount to much; a successful man could hide his past; an unsuccessful man sat in his.”) and ultimately decides to change his fate, pulling a fast one on the reader in the process. Lehane’s tale stands out as welcome relief to the anthology’s gloom and doom— it is one of the few with a happy ending.

The above tales, as well as Jim Fusilli’s and Dana Cameron’s contributions, are deftly and simply written. Sturdy plot lines draw the reader into the story where he or she will find their own failures and yearnings mirrored in the protagonists’ lives.

Be warned, however, that the more successful stories are in the beginning of the book. Once you reach mid-way the quality of the writing becomes more variable, the volume peppered with less compelling, clunkier instances of crime. Perhaps the pleasure lessens because the more stories you read the more you realize there’s a 75 percent chance someone is going to get axed. Hence, you spend your time trying to figure out who it is and when it will happen instead of enjoying characterization and plotting.

Even given that reasoning, some of the tales are less appealing because they don’t play fair with the reader — they leave unanswered questions and bewilderingly murky motivations.

It doesn’t make very much sense that Patricia Powell’s protagonist doesn’t report to the police that she has an escaped prisoner in her home. She worries about the dangerous stranger and at one point tries to call the cops before she realizes the phone line is cut. But when she finally gets the chance to tattle, she doesn’t, and Powell doesn’t provide a good enough reason why.

The shifting timeline and locations in Itabari Njeri’s “The Collar” causes unnecessary confusion. Too many side stories overwhelm the main plotline, and I was left wondering what I was supposed to take away from the tale.

Stewart O’Nan’s contribution is about a young woman who cares for her older father through an arrangement of deceptive machinations. While intriguing in concept, the story doesn’t bother to provide much understanding of the main character’s motivations or feelings—there was too much action and reaction, not enough psychological depth.

John Dufresne’s “The Cross-Eyed Bear” weaves a hauntingly sad tale of a priest who has been accused of molestation. The premise of this story caught my attention; some of the reasoning behind the figure’s priestly sin was jarring and rang true. (“You snap on the Roman collar, and you have instant respect without having earned it.”) But the story overemphasized ambiguity to the point that the reader is left wondering about essential issues of identity and resolution.

Despite the anthology’s unevenness, most of the tales provide pleasure in one way or another. Part of the excitement comes from the narrative twist and turns, coupled with surprising and enticing conclusions. (Like when we find out Lehane’s lonely poor old Bob is much more than just a devout puppy lover.)

Moreover, despite committing such despicable acts as stealing babies and robbing cash-only restaurants, most of the protagonists earn the reader’s empathy. They are living out our dark fantasies for us—taking on the mantle of action at all costs; fighting for their pain-ridden lives to be better instead of standing aside. Some of the characters could be said to win the fight, while other fail horribly. But it doesn’t matter to us—we’re busy sitting back and relishing our darkest thoughts being acted out by others.

Despite its ups and downs, Boston Noir digs memorably into the reader’s darkest thoughts while taking a stroll through Boston’s gritty time and space. Just keep in mind that the bucketfuls of messy, dastardly life the anthology drudges up will give you 11 more reasons to look over your shoulder as you walk the streets at night.

Tagged: Akashic Books, Boston, Boston Noir, Dennis Lehane, book review, fiction