Jazz Album Reviews: A Roundup of Recent Recordings

By Jon Garelick

An occasional feature that looks at current jazz albums of interest.

Kris Adams & Peter Perfido, Away (Jazzbird) With two nominal “leaders” and no clear unifying theme, this album nonetheless comes off as satisfying and nourishing as a carefully planned, beautifully executed concert program. Drummer Perfido put this band together as a tribute to his late friend and colleague, guitarist Michael O’Neil, who died in 2016, recruiting singer Adams, pianist Bob Degen, and bassist André Buser.

Kris Adams & Peter Perfido, Away (Jazzbird) With two nominal “leaders” and no clear unifying theme, this album nonetheless comes off as satisfying and nourishing as a carefully planned, beautifully executed concert program. Drummer Perfido put this band together as a tribute to his late friend and colleague, guitarist Michael O’Neil, who died in 2016, recruiting singer Adams, pianist Bob Degen, and bassist André Buser.

It’s an odd mix: Dedicated to O’Neil, it includes nine of his compositions, two by Paul Motian, and one by guitarist Eric Schultz, who does not play on the album. Four of the vocal features are wordless. The two opening songs, by O’Neil (“Play,” “Here”), could have come out of musical theater; they don’t necessarily set you up for the gentle free-jazz turbulence and pulse that threads its way through the album.

But, as the album unfolds, it’s clear the unifying factor isn’t O’Neil or Motian, or even Adams as featured vocalist. It’s this band as a whole, fluid in every context, in which Adams is simply the lead horn, clear and bright whether delivering the lyrics with conversational directness or floating long-toned wordless lines in vocal numbers that include extended trio passages and one group improvisation (“Free One”). Two by O’Neil easily upend the expectation of those two openers: “No Ordinary Girl,” a textured character portrait using words and extended improvisation for voice and the trio, and the duo “Blessing” in which Buser’s uncommonly lyrical, singing electric bass lines are a perfect complement to Adams’s rendering of the simple, affecting lyrics.

Lina Allemano Four, The Diptychs (Lumo) For some of us (well, me), the sound of a “pianoless” quartet with horns, bass, and drums hits a jazz sweet spot. Think of Gerry Mulligan with Chet Baker as an early prototype: two melody instruments in sparely orchestrated, easy swinging counterpoint, unleashed from the harmonic tyranny of piano or guitar. In other cases, the tantalizing ear taffy of harmonic ambiguity grows even richer: Mingus with Eric Dolphy, Ted Curson, and Dannie Richmond; Ornette Coleman with Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, and Ed Blackwell; or even more recently, Oliver Lake with Graham Haynes, Joe Fonda, and Barry Altschul in the OGJB Quartet. As “free” as this jazz gets (in my ideal, anyway), you can almost always depend on the anchoring of unison melodic lines and varied grooves.

Lina Allemano, a 52-year-old Canadian trumpeter and composer who alternates between Toronto and Berlin, has been leading the current lineup of the Lina Allemano Four since 2005 (a short-lived version popped up in 2003), with alto saxophonist Brodie West, double bassist Andrew Downing, and drummer Nick Fraser. There are also a couple dozen various projects under her name on Wiki, and a slew of side gigs.

Though I was only vaguely aware of her other recordings, Allemano’s Diptychs grabbed my ear immediately with its barely sketched forms, continuous free play, and a sonic intimacy easily captured in the unfussy production.

Allemano likes form; her 2023 album Canons is an explicit exploration of that form for trumpet and chamber ensembles. So there’s always something guiding the ear. As the title suggests, the pieces are organized in “diptych pairs.” The main theme of “Positive” is an ascending double helix of melody lines, while “Negative” descends. “Resist” punches aggressively with alternating repeated single notes from trumpet and alto. “Coalesce” starts with the amity of waltz time in ballad tempo. “Scrambled” starts with a low-register bowed-bass grumble and a melody that quietly accelerates into all manner of free time and extended techniques (lots of spit and split tones in Allemano’s trumpet here). And “Over Easy” (the longest track here, at 9:49) also extends ensemble freedoms as they push a simple melodic idea, but without pressing.

The delicacy of the interactions and the transparency of textures — however “noisy” — are a constant source of pleasure here. And more than, say, the Four’s 2010 Jargon, the emphasis is on ensemble effects rather than solos. But from moment to moment, it’s thoroughly engaging, enhanced by that intimate production and each player’s sure control. You’re right there with these musicians as they figure out where to take their four-way conversation next.

Ran Blake & Jared Sims, Night Harbor (indie) How many ways can you say, “I love you”? That could be a subtext for this album, or even for Ran Blake’s entire career. It could also account for the regular repetition of some songs over the course of the pianist/composer’s many recordings. Blake turned 90 last April. He recorded these 16 performances in 2023 and 2024 with his former student and longtime collaborator Jared Sims, here on baritone sax. Three tunes are played twice, and one (Ornette Coleman’s “Sadness”) three times. The repetitions don’t follow each other. There are no “master” or “alternate” takes here. Rather, the album works like a sequence in which each reprise is meant to comment on what came before and what follows. So, “Sadness” is the second track, following Raymond Hubbell’s “Poor Butterfly” and preceding Pete Rugglio’s “Collaboration.” Then it comes back, following Tommy Goodman’s “Driftwood” and preceding J. Fred Coots’s “You Go to My Head.” And finally, it comes between the album’s two performances of “Almost Like Being in Love.”

What to make of these juxtapositions? The film noir-obsessed musician has said that the genre’s portrayal of obsession is part of what attracts him to it. So don’t be surprised to see familiar Blake selections (I’ve now seen and heard “Driftwood” on so many Blake recordings, and in so many of his live concerts, that I had lazily assumed he wrote it).

What you get is the uncanny lived-in experience of Blake’s performances, not just in his precisely off-kilter reharmonizations, but dynamics and the drama of entrances and exits and fade-outs. Often, Sims plays the straight man, as in opening “Poor Butterfly,” where his rich-toned delivery of the opening melody is echoed by Blake before drifting into shimmering dissonant sustained chords. On the first take of “You Go to My Head,” after offering his usual chiaroscuro chording, Blake plays a delicate, single-note line of the melody, both perfectly phrased and perfectly vulnerable.

As usual with Blake, tempos in these 16 selections (in 45 minutes) are generally slow. There’s some antic-Weimar-like agitation in “Dr. Mabuse,” and Blake’s emotionally complex “The Short Life of Barbara Monk” (for Thelonious’s daughter) has an oom-pah-pah carousel theme. Max Roach’s “Mendacity” summons the appropriate rhythmic agitation. But the mood is generally balladic, elegiac. “Almost Like Being in Love,” despite its upbeat passages, emphasizes the “almost.” Maybe that’s why there are three versions of “Sadness,” or why several of the performances end abruptly, sometimes in the middle of a phrase. The closing “You Go to My Head” fades in midair, as if on a sigh.

Blink, Blink (Driff) As I’ve said elsewhere in The Arts Fuse, generalizations about the music of saxophonist and composer Jorrit Dijkstra tend to fall short. In his eloquent liner notes to Blink, Dijkstra cites African highlife, Indonesian gamelan, Delta blues guitar, and African balafon to account for the music’s “organic swells in dynamics and density.” But the quick takeaway comparison here is Ornette Coleman’s Prime Time, with two guitars (Eric Hofbauer and Gabe Boyarin), electric bass guitar (Nate McBride), drums (Eric Rosenthal), and Dijkstra’s alto. There are all manner of layered rhythms and tempos here, and the guitars are tuned a quarter-note sharp, for that extra bit of Ornette-like frisson of off-balance ensemble ecstasy. The result is free, but also highly ordered. Dijkstra favors keening folk-like alto melodies in the Coleman manner, and Hofbauer often joins him in loose unison amid the surrounding ruckus. Some pieces, like “Yet,” are slow and contemplative, while “Pulse” rides on the solid funk of what I think of as African 6/8. “Hop” shows Dijkstra’s affection for Steve Lacy, with a nearly uncountable ADHD-like staccato repetition of short modular phrases. Throughout, Nate McBride’s electric bass often acts like a third guitar line, further enhancing the web of sound.

Blink, Blink (Driff) As I’ve said elsewhere in The Arts Fuse, generalizations about the music of saxophonist and composer Jorrit Dijkstra tend to fall short. In his eloquent liner notes to Blink, Dijkstra cites African highlife, Indonesian gamelan, Delta blues guitar, and African balafon to account for the music’s “organic swells in dynamics and density.” But the quick takeaway comparison here is Ornette Coleman’s Prime Time, with two guitars (Eric Hofbauer and Gabe Boyarin), electric bass guitar (Nate McBride), drums (Eric Rosenthal), and Dijkstra’s alto. There are all manner of layered rhythms and tempos here, and the guitars are tuned a quarter-note sharp, for that extra bit of Ornette-like frisson of off-balance ensemble ecstasy. The result is free, but also highly ordered. Dijkstra favors keening folk-like alto melodies in the Coleman manner, and Hofbauer often joins him in loose unison amid the surrounding ruckus. Some pieces, like “Yet,” are slow and contemplative, while “Pulse” rides on the solid funk of what I think of as African 6/8. “Hop” shows Dijkstra’s affection for Steve Lacy, with a nearly uncountable ADHD-like staccato repetition of short modular phrases. Throughout, Nate McBride’s electric bass often acts like a third guitar line, further enhancing the web of sound.

Dijkstra compares these structured improvisations to other “group behavioral patterns such as insect swarms and bird flocks.” But for the most part, you can enjoy a colorful, elastic groove. And even in a collective ensemble approach like this, which favors group effect rather than solos, you can savor the embedded details, such as Rosenthal’s quiet, sustained passage in “Yet,” where he matches continuous light snare hits with the snip-snip-snip-snip of his hi-hat, or Dijkstra’s ardent alto cries on “Trans.”

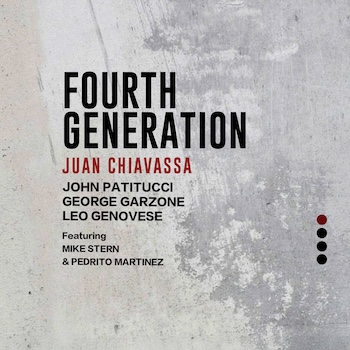

Juan Chiavassa, Fourth Generation (Whirlwind) You could call this an old-fashioned blowing session: four heavyweights digging into easily digestible forms and letting it rip. Listen, for one, to “Hey Open Up,” a George Garzone composition, where pianist Leo Genovese offers a master class in inventive exuberance, or the way Garzone, on tenor, comes hurtling out of a little free-fall cadenza mid-tune. Drummer Chiavassa has brought together Garzone, Genovese, and bassist John Patitucci, with guest spots from Mike Stern (guitar), Pedrito Martinez (percussion), and Federico Gonzalez Peña (synthesizers). The material is built around a core of blue-chip player-composers (Joe Farrell, Wayne Shorter, Joe Henderson), with four of its 10 tracks by Garzone — an added treat from a great player whose main platform, the Fringe, these days sticks to free improv. “I hate reading,” Garzone said at a gig by another player not long ago. Glad he got out the reading glasses for this one.

Juan Chiavassa, Fourth Generation (Whirlwind) You could call this an old-fashioned blowing session: four heavyweights digging into easily digestible forms and letting it rip. Listen, for one, to “Hey Open Up,” a George Garzone composition, where pianist Leo Genovese offers a master class in inventive exuberance, or the way Garzone, on tenor, comes hurtling out of a little free-fall cadenza mid-tune. Drummer Chiavassa has brought together Garzone, Genovese, and bassist John Patitucci, with guest spots from Mike Stern (guitar), Pedrito Martinez (percussion), and Federico Gonzalez Peña (synthesizers). The material is built around a core of blue-chip player-composers (Joe Farrell, Wayne Shorter, Joe Henderson), with four of its 10 tracks by Garzone — an added treat from a great player whose main platform, the Fringe, these days sticks to free improv. “I hate reading,” Garzone said at a gig by another player not long ago. Glad he got out the reading glasses for this one.

Jon Garelick can be reached at garelickjon@gmail.com.

Tagged: "Away", "Fourth Generation", "Night Harbor", "The Diptychs", Blink, Jorrit Dijkstra, Juan Chiavassa, Kris Adams & Peter Perfido, Lina Allemano Four