Arts Remembrance: Robert Scanlan — An Animating Force in Boston-area Theatre for Nearly Five Decades

“An inspiring intelligence combined with a high level of artistry is a rarity in the arts. With the loss of Bob Scanlan, the worlds of both theatre and poetry have cause to mourn.”

The late Robert Scanlan — a giant in the evolution of what we know as the theatre today. Photo: Joanne Baldine

Director, actor, writer, teacher, and scholar Robert Scanlan passed away on May 30 at the age of 77. There will be a Memorial Gathering in his honor today at 11 a.m. in Story Chapel, located at the entrance of Mt. Auburn Cemetery, 580 Mt. Auburn St, Cambridge. (The event can be watched on Zoom at this link.) The tributes to Bob below offer a glimpse into his wide-ranging career as an artist, professor, impresario, and director. His dedication to supporting stage work that challenged rather than placated was an inspiration to me and so many others.

I was always after Bob to write pieces for The Arts Fuse. Occasionally, I succeeded. He contributed moving words of remembrance for actor Alvin Epstein, and reviewed Samuel Beckett’s early work Echo’s Bones and The Collected Poems of Samuel Beckett. The last time I interviewed him was about directing, in August 2024, Praxis Stage’s staging of Max Frisch’s The Arsonists. His interest in this play — a satiric attack on the self-destructive indifference of the bourgeois — reflected Bob’s alarm at the political direction the country was taking. And his belief that theater should speak to that crisis, rather than ignore it.

For me, and many others, he was a theatrical guiding star, a dependable voice that proselytized for demanding theatrical experiences that strove for thought, lyricism, passion, and provocation. Anything but the overly commercialized sugar highs churned out by too many Boston area stage companies. Bob was often disappointed with what was going on in the local theater scene, but his critiques were accompanied by wry humor and a sympathetic understanding of the odds against doing substantial work in today’s transactional world. Bob lamented — with genial sadness — the aesthetic and spiritual degeneration of his beloved American Repertory Theater into a pre-Broadway tryout house.

For those who love theater and poetry that demand our attention — “men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there” — he will be missed.

— Bill Marx

Robert Scanlan with Seamus Heaney in 2013, a few months before Heaney died. Photo: Joanne Baldine

Robert Scanlan, who passed away on May 30th, loved the theatre. He was also a giant in the evolution of what we know as theatre today. You could, with evidence to back it up, call him the father of modern dramaturgy. As Literary Director at the American Repertory Theatre, as a beloved teacher to hundreds of students at Harvard and MIT, as a director, and as an author, he sought to do the seemingly impossible: unlock the passion of drama through an intellectually rigorous exploration of form and content. He often succeeded. I will never forget his Elliot Norton Award-winning production of An Evening of Beckett at the A.R.T. Thirty years on, it still ranks among the best productions I have ever seen. Using the simplest tools in a converted rehearsal hall in Harvard Square, he captured the very essence of Beckett—pure, desperate humanity expressed through an extremity of form. I shall never forget the incomparable Tommy Derrah, floating above a void in an orb of white light, performing “A Piece of Monologue.” The terrifying power and pathos of that moment still give me chills today.

Bob helped usher in a golden age of dramaturgy in the American theatre. His famous plot-bead diagrams (a device for exploring and organizing the essential structure of a play) revolutionized pre-production for directors and their literary teams. Sadly, in the face of today’s financial challenges, the dramaturg is among the first to be tossed off the liferaft at all but the largest theatres, but Bob’s influence remains profound.

I first met Bob when he served as dramaturg for the A.R.T., back when it still had a resident acting company. In those days, auteur directors would pass through with their dazzling but often inscrutable concepts for the classic plays we did. Many were European, and communication was not always their strong suit. Bob was a welcome presence behind the production table, providing clarity and reassurance to us befuddled actors. He had a talent for finding simple, accessible language to explain the most esoteric concepts. He made dramaturgy essential to the process, helping everyone keep track of what we were trying to accomplish. He would often act as a translator between us and the fiery geniuses, and in that way help them better understand what they were trying to make. Dario Fo, the great Italian comedian, valued Bob so much that he insisted Bob and his wife Joanne host a celebratory party for their production, a party that lasted two days. (Arts Fuse review of Bob Scanlan’s staging of Mistero Buffo.)

His skill as an intermediary went well beyond our rehearsal room. Bob was an intimate of Samuel Beckett (and distinguished President of the Samuel Beckett Society), and one of the few people trusted by Beckett’s fanatically protective estate, which would resist almost any artistic invention that went beyond what was written on the page. Bob would frequently mediate between the estate and American companies that wanted to do Beckett’s plays, but wished to contribute their own artistic perspective to them.

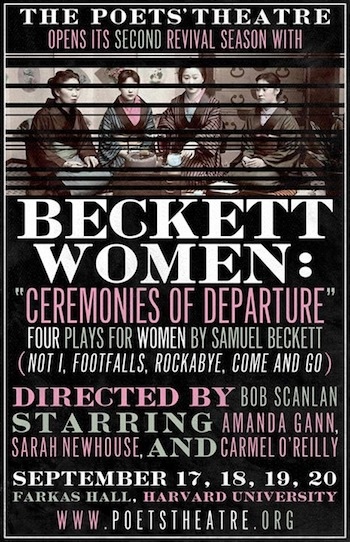

Perhaps dearest to Bob’s heart was The Poets’ Theatre. Over the years, when he and I would meet, he would speak rapturously about his experiences there. Founded in 1950 by a coterie of poets and artists, including Dylan Thomas, Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, and Edward Gorey, it died and was reborn many times. Bob was part of a revival during the 80s and 90s. It offered him what he loved best—language, rich in form and structure, combined with the rough-and-tumble verve of live performance. The enthusiasm with which he spoke about it (though, to be fair, Bob was enthusiastic about almost everything) so inspired me that in 2014, he and I, along with David Gullette and a loyal troupe of supporters, revived the company yet again. As Artistic Director, Bob framed the vision that allowed us to do some extraordinary work, including a joyous restaging of Dylan Thomas’s Under Milkwood at Sanders Theatre; a Viking feast of Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf; yet another landmark Beckett production in Beckett Women, which triumphed in Cambridge and in Belfast, Ireland; and my own play Albatross, which garnered us another couple of Elliot Nortons. I will be forever in his debt for his championing of my play.

Perhaps dearest to Bob’s heart was The Poets’ Theatre. Over the years, when he and I would meet, he would speak rapturously about his experiences there. Founded in 1950 by a coterie of poets and artists, including Dylan Thomas, Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, and Edward Gorey, it died and was reborn many times. Bob was part of a revival during the 80s and 90s. It offered him what he loved best—language, rich in form and structure, combined with the rough-and-tumble verve of live performance. The enthusiasm with which he spoke about it (though, to be fair, Bob was enthusiastic about almost everything) so inspired me that in 2014, he and I, along with David Gullette and a loyal troupe of supporters, revived the company yet again. As Artistic Director, Bob framed the vision that allowed us to do some extraordinary work, including a joyous restaging of Dylan Thomas’s Under Milkwood at Sanders Theatre; a Viking feast of Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf; yet another landmark Beckett production in Beckett Women, which triumphed in Cambridge and in Belfast, Ireland; and my own play Albatross, which garnered us another couple of Elliot Nortons. I will be forever in his debt for his championing of my play.

I mentioned Bob’s enthusiasm. His favorite word was “astonishing.” He found many things astonishing: nature, science, poetry, and, of course, theatre. But he was not easy to astonish because his standards were low, or because he was credulous. He had a rare gift for seeing the wonder that lies even in the mundane, the beauty that most of us overlook. He loved life, and when he saw it, it would send him into paroxysms of excitement. His enthusiasm was infectious, and his elation would fuel those around him and drive them to greater heights.

He loved going to the theatre, and would always focus more on the successes he saw than on the shortcomings. He was fiercely loyal, especially to artists, and would wax rhapsodic about performances and plays he saw, always managing to give one a jolt of confidence.

Fundamentally, Bob Scanlan gave his life to the theatre because he loved its people. He loved people in general. Gregarious and inquisitive, he could talk to anybody, and made friends wherever he went. He was a great storyteller, with a big helping of the Irish “gift of the gab.” He could talk his way into almost anywhere. Robert Scanlan loved the theatre because he loved people, and at its core, that’s what the theatre is really about: people.

— Ben Evett is the Founding Artistic Director of the Actors’ Shakespeare Project and former Executive Director of the Poets’ Theatre. He was a member of the Resident Acting Company at the A.R.T. from 1993 to 2003.

The late Robert Scanlan. Photo: Joanne Baldine

Animateur is one of those French words, like élan, that has no direct English equivalent. It means the dynamic agent in a collective, especially a cultural, enterprise. Unlike an “influencer,” an animateur takes active part in organizing, directing, shaping that enterprise. Robert Scanlan was just such an animating force in Boston-area theatre for nearly five decades. Now we have lost him.

While others may be more prominent in headlines and celebrity journalism, Scanlan carried on, often behind the scenes, to foster the highest forms of literary drama and innovative staging. He collaborated closely with many of the most exciting and influential theatre artists of the last century, among them Eugène Ionesco, Dario Fo, Robert Wilson, and Ping Chong. He lectured and staged plays from Hanoi to Madrid, from Beijing to Belfast, from Cracow to Strasbourg. In the process, his influence spread far beyond local fame.

Scanlan had been brought up in postwar France which in part explains his cosmopolitan outlook. Integral to his aesthetic is his relationship to Samuel Beckett. Beckett was a personal friend, and they shared an Irish background and a French sensibility. Scanlan devoted much of his career to interpreting, directing and campaigning the expatriate author. His evening Beckett Women: Ceremonies of Departure was fêted when it was taken to Belfast, and he worked to integrate the Beckett canon with musicians and scenographers. His engaging lectures on Beckett were packed with insights, and he dined out on his Beckett anecdotes. When I played Krapp’s Last Tape at Tufts some years ago, I was relieved to find that Scanlan approved of my performance.

Bob Scanlan and I first met at the Loeb Drama Center in Cambridge in 1973. (We veterans of Harvard theatre still refer to it as the Loeb for we regard the A.R.T. as a cuckoo in the nest.) In those days, the Harvard Summer School sponsored a repertory of four plays and an intensive acting program for young people. Scanlan was stage manager for the plays and I ran the acting program. He was proud of the fact that he played the janitor Schlosser in the revival of Odets’s Awake and Sing! in which Morris Carnovsky took the role of the grandfather he had created for the Group Theatre in 1935.

For nearly a decade Scanlan, an alumnus of M.I.T., worked there as Director of Drama, along with the legendary Joe Everingham. When the A.R.T., took possession of the Loeb, Robert Brustein had the perspicacity to name Scanlan its Literary Director. Literary Director may be a rough translation of Dramaturg, another term with no exact equivalent in English. In Germany, where the word and the concept originated, a dramaturg is a partner of a theatre’s Intendant or artistic director: he shares in shaping the repertoire and the theatre’s artistic profile, advising on script revision and translation, overseeing publicity, and serving as the company’s public face. In the US, often the “literary manager” merely writes the program notes.

At the A.R.T., with the empire-building Brustein at the helm, there could be no question of Scanlan being a full partner. However, he hosted a number of innovative troupes and artists, and helped to organize important performance installations and media experiments. One benefit of his position was teaching drama (The Greeks to Ibsen) in the English department. Harvard’s relation to theatre has always been problematic; although it houses one of the finest theatre collections in the world, although its students and some of its faculty have been hyperactive in staging performances everywhere they can, although it now sanctions a performing arts program, it has never been willing to accept the study of theatre as a formal discipline deserving of departmental status.

Scanlan in his classes was able to impart to the students a huge fund of knowledge and a discerning critical acumen. Many of them were inspired to pursue a career in the arts. His instruction, informed by his practical work, eventuated in a seminal publication, Principles of Dramaturgy (Routledge, 2019). It promoted “form” and “action” as the fundamental building blocks of a play. Meanwhile, Harvard had begun to question the academic soundness of many of the A.R.T.’s degree-giving programs taught by unqualified members of the company. In eliminating those programs, it threw out the baby with the bath-water and Scanlan’s official connection with the faculty was severed. This enabled him to direct his energies to The Poets’ Theatre.

Founded in 1950, the Poets’ Theatre had fostered the work of a great many talents, with readings and staged performances at various venues in Cambridge. The burning of its primary theatre space in 1962 seemed to spell its demise, but, Lazarus-like, it was brought back to life in 1986. That was when I first became involved with it, directing the premiere of Jonathan Katz’s play about Walt Whitman and his boys, Comrades and Lovers, at Agassiz Theatre in 1992. However, the Poets’ Theatre had endemic problems of funding, organization, and lack of permanent housing. As its new Artistic Director, Bob Scanlan determined to put it on a firm footing with more frequent appearances, a more conspicuous public presence, and sound financial backing. I readily agreed when he asked me to serve on its newly-formed Advisory Board.

Bob Scanlan and his wife Joanne in 2023. Photo: Joanne Baldine

Scanlan inaugurated this latest renascence with a gala reading of Dylan Thomas’ Under Milkwood, which had first been performed by the original Poets’ Theatre. He assembled across the width of the Sanders Theatre stage an impressive cast consisting partly of past A.R.T. luminaries (Cherry Jones, Alvin Epstein) and local poets (Lloyd Schwartz, David Gullette). Intended as a fund-raiser, it initiated a series of readings, again in varied locales from the Boston Athenaeum to the Cambridge Arts Center. Scanlan had a special talent as a conduit bringing poets to the stage; Seamus Heaney, Derek Walcott, Yusef Homunyakaa, and a host of young, often minority, poets have received new audiences through his staging of their work. He had a mandate to create performance pieces from literary and historical sources, and achieved this with flair and brilliance: “A Muster of Poets,” Dante in Robert Pinsky’s translation, abolitionist speeches and immigration documents, adaptations of Gilgamesh and Beowulf, Adams family memoirs, poetic monologues. Much of Scanlan’s Beckett work was produced under the aegis of Poets’ Theatre which had its own Irish connection. It had had been founded by Dublin-born poet and actress Mary Manning (otherwise, Molly Howe).

Scanlan widened the scope of the Poets’ Theatre. One outreach was to the Purcell Society, for which he staged Dryden’s King Arthur with the original music. The association with the Society continued when I wrote verse narration and performed it for Dryden’s The Tempest and Davenant’s Macbeth. Scanlan had a long wish list of future projects for the Poet’s Theatre, including an evening of Berlin cabaret lyrics and a tribute to Edward Gorey who had been a member and designer of the group’s first avatar.

As Scanlan’s health declined, his work in the theatre became more explicitly engagé (as he would put it). For Praxis Stage in Chelsea he revived Max Frisch’s The Arsonists, with its warning of denial, whether of fascism or global warming. His last endeavor was to promote John Okrent, a physician who, like William Carlos Williams, is also a poet. Readings of his verse concerning the Covid-19 epidemic are still being performed

An inspiring intelligence combined with a high level of artistry is a rarity in the arts. With the loss of Bob Scanlan, the worlds of both theatre and poetry have cause to mourn.

— Laurence Senelick is Fletcher Professor Emeritus of Drama and Oratory at Tufts University and a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. His latest publication is a translation of Prometheus Bound.

When I interviewed actor/clown Bill Irwin for this magazine, he told me he was looking forward to having dinner with Bob Scanlan before his homage-to-Beckett performance at Arts Emerson. “I wouldn’t think of performing Beckett in Boston without first talking to Bob Scanlan,” Irwin said.

The last time Bob and I spoke was at a performance of Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood that brought a disparate group of theatergoers together in Cambridge to enjoy what turned out to be a wondrous yet melancholy evening. He was thrilled by the turnout. He spoke that night of other projects he was plotting.

Perhaps a fitting epilogue to Bob — encapsulating life’s ephemeral nature — are the last lines of British poet Edward Lear’s poem “Calico Pie”:

Calico Drum,

The Grasshoppers come,

The Butterfly, Beetle, and Bee,

Over the ground,

Around and around,

With a hop and a bound,–

But they never came back to me!

They never came back!

They never came back!

They never came back to me!