Theater Interview: “Mistero Buffo” — Seriously Funny

Socialism is no longer a discredited word, and Fo brings an impish sense of divine comedy to the clash between the haves and the have nots that Bernie Sanders misses.

Ben Evett (r) and Remo Airaldi (l) in The Poets’ Theatre production of “Mistero Buffo.” Photo: The Poets’ Theatre.

By Bill Marx

When playwright/performer Dario Fo visited the American Repertory Theater in 1986 he gave a performance at the Hasty Pudding Theatre that I have never forgotten. In The Grammelot of the Zanni he mimed the hunger of a 14th century peasant who was famished to the point that the only thing left to eat was himself. The character then went about cannibalizing his innards: plucking out his eyeballs and popping them into his mouth as if they were bonbons, zestfully pulling out his intestines and slurping them up as if they were deliciously long strands of spaghetti. When I mention this visceral farce routine to people, I usually get a quick reaction of ‘Yuck,’ but Fo’s was an exuberant, even exhilarating act of dramatic anarchy, exhilarating in its physical inventiveness as well as its head-spinning artistic reach — political protest, black comedy, theater of the absurd.

Fo’s distinctive mix of humor, humanity, and protest was fashionable three decades ago, but productions of his work have become rare. Even his picking up a Nobel Prize in Literature didn’t jump start the appearance of his scripts in American theaters. The economic sway of the world’s pitiless exploiters — from the 1% to governments, corporations, and religions — has only grown, but our stages have been reluctant (perhaps out of fear that mocking the powers-that-be will offend well-heeled audience members?) to focus on issues of “class warfare.”

Of course, Fo’s satire has become more relevant than ever, as Ben Evett playing a Giulllare (Clown) laments in The Poets’ Theatre production of Mistero Buffo: the Gospel according to Dario Fo (at Suffolk University’s Modern Theatre through March 26). Like Bernie Sanders, Fo is a proud socialist. “Real socialism is inside man,” he has written. “It wasn’t born with Marx. It was in the communes of Italy in the Middle Ages. You can’t say it is finished.” Socialism is no longer a discredited word, and Fo brings an impish sense of divine comedy to the clash between the haves and the have nots that Sanders misses.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of Fo and his wife France Rama’s visit to Cambridge; Fo turns 90 in two days. (An international symposium dedicated to the “Epic Theater of Dario Fo and Franca Rame: Between Tradition and Innovation” will be held on Fo’s birthday at Harvard University. ) I sent some questions, via e-mail, to Robert Scanlan, director and co-translator (with Walter Valeri) of Mistero Buffo. Scanlan hung out with Fo 30 years ago at the A.R.T. and he has perceptive things to say about the need for new translations, the complexity of Fo’s dramatic vision, and the challenges of directing his work.

Arts Fuse: Dario Fo turns 90 on March 24. There was a fashion for his plays in the Boston area during the ’80s and ’90s (he visited the American Repertory Theater, performing a solo piece as well as directing one of his plays). But even with a Nobel Prize under his belt there have been few productions of his scripts over the past decade or so in the area. Why do you think that is?

Robert Scanlan: My guess is because existing translations misfire and misrepresent Dario Fo and his accomplishments. His texts are rendered by British translators as though they were meant to be Monty Python sketches. I find them silly. Dario Fo has a much greater comic range than that farce and gag rhythm people have tried to make him into.

Also: only a very few of his texts are available at all in English. His status as a Nobel Prize winner is not reflected in the quality of available translations in English.

AF: Besides celebrating Fo’s birthday, what does this production of Mistero Buffo bring to American audiences that they need to hear? Why not do another of his plays, such as his popular anti-consumerist farce We Won’t Pay, We Won’t Pay?

Scanlan: The selection of Mistero Buffo texts that Walter Valeri and I put together is a new presentation altogether. We chose five texts out of dozens that make up the complete “Mistero Buffo” collection. No one ever does more than four or five in any production. Our selection is original: it creates a view of the Passion Week and reveals a deeply populist take on religion. It may come as a surprise to many that Fo equates Christ with compassion and sympathy for all who suffer. He is against big shots who oppress the poor and the miserable, whether they be “padrones” or a heavy-handed religious hierarchy. But his images of Christ are remarkably divine. Time to see that. People misled into expecting only jokes will be surprised.

Debra Wise in The Poets’ Theatre production of “Mistero Buffo.” Photo: The Poets’ Theatre.

AF: What are the challenges that this script poses to you as a director? I assume the actors have to walk the thin line between satire and farce.

Scanlan: Well since I translated it myself, I took care of my potential difficulties as a director up front. I wrote the script I wanted to direct, and it is meticulously faithful to the final version of these scripts left behind by Dario Fo and Franca Rame. However, all translators have enormous interpretative responsibility. I used the definitive Einaudi edition revised a final time by Franca Rame just before she died in 2013. These are therefore really new versions in English. But I also “channeled” these remarkable artists based on my friendship with them thirty years ago.

AF: Why a new translation of Mistero Buffo into English? There are a number already available — what are you providing that earlier translators have missed? Updated references? There is an opening section that sets out the history of the Giullare clown figure and the history of the text.

Scanlan: I find the other translations mediocre to bad to totally distorted. Mine and Walter’s are better. Walter Valeri, a member now of the Poets’ Theatre (and our company Dramaturg) worked closely with the Fos for over twenty years. He is an intimate of theirs and an undisputed authority on their work. He is also an accomplished poet in Italian. We’re presenting ourselves, with Fo’s explicit blessing, as the real deal.

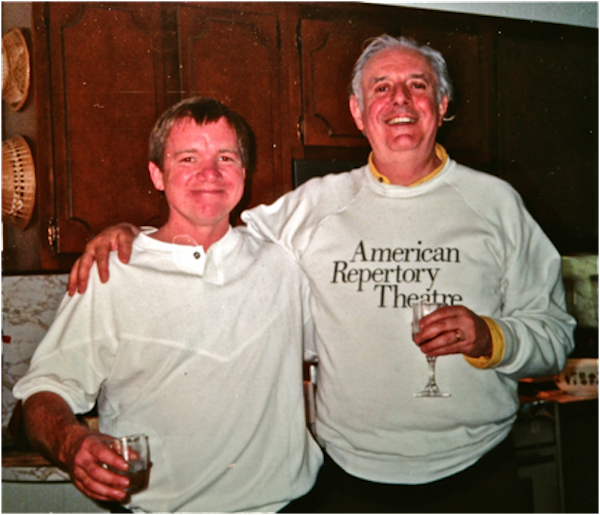

Robert Scanlan and Dario Fo at the American Repertory Theater in 1987. Photo: The Poets’ Theatre.

AF: Talk a bit about Fo’s comic approach and its connection to black comedy. “The Blind Man and the Cripple” gives us the eponymous characters doing their best not to be “miracled” — healed by God.

Scanlan: That’s the cripple’s take, and it is one of the actually medieval texts Dario Fo re-wrote for his Mistero Buffo (Samuel Beckett also wrote his own version of this same medieval text: “Rough for Theatre I”). The Blind Man does gets bamboozled into a panic about being “miracled” but changes his mind when Christ restores his sight. The parable illustrates how “one is saved, and the other damned.” As Sam Beckett put it: “It’s a reasonable percentage.”

AF: When Mistero Buffo was first produced it was condemned by some critics as anti-Catholic — a television broadcast of the script was denounced by the Vatican as “blasphemous.” We have a new, kinder and gentler, Pope — does the piece still pack all that much punch? Would the Church bother to condemn it today?

Scanlan: Far be it from me to guess what “The Church” would dare to do about Mistero Buffo. After Spotlight they had better lay low for another decade of more… But the play is probably correctly identified as anti-Popish, and therefore anti-Catholic. That turns out to be very different from its being in any way disrespectful of Christianity. These plays and buffooneries clearly portray Christ as authorizing any resistance to pompous assholes (I’m quoting the play) who lord it over simple, hard-working people. Dario Fo and Franca Rame clearly sided with the working class and these skits support the idea that the Catholic Church betrayed the teachings of Christ by siding with landowners and aristocrats and preaching submission to temporal power and economic injustice.

AF: Do you have a favorite among the play’s episodes? And why?

Scanlan: Walter Valeri and I chose these plays as a suite, with each one leading into the next, and the whole set of five taking us from the Birth of the Giullare, through Jesus’ first miracle (the Wedding at Cana) and on through to the passion. I therefore have trouble picking a favorite when all of them are stations on the way to the culmination at the cross. Also, my brilliant cast, three of the finest actors in Boston (Ben Evett, Remo Airaldi and Debra Wise) are impossible to rank. They are all virtuoso in their respective parts. Their ensemble work is divine.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Ben Evett, Dario Fo, Debra Wise, Mistero Buffo, Modern Theatre, Remo Airaldi, Robert Scanlan