Opera Album Review: A World-Premiere Recording of a Sprightly Three-Act Operatic Comedy from 1882

By Ralph P. Locke

Joachim Raff’s energetic and characterful Die Eifersüchtigen hits its mark, in its first production ever.

Joachim Raff: Die Eifersüchtigen (The Jealous Ones)

Serafina Giannoni (Donna Rosa), Raìsa Ierone (Donna Bianca), Mirjam Fässler (Ninetta), Benjamin Popson (Don Claudio), Batthias Bein (Beppino), Balduin Schneeberger (Don Giulio), Martin Roth (Don Geronimo).

Orchestra of Europe, cond. Joonas Pitkänen.

Naxos 660561-62 [2 CDs] 138 minutes.

To purchase or to try a track, click here.

Joachim Raff (1822–82) was one of the most renowned composers in the German-speaking lands throughout his lifetime. Born in Switzerland, he served as Liszt’s musical assistant from 1850 to 1856 but broke with Liszt, preferring to go his own way. He moved to Wiesbaden, where he made a living teaching and composing piano and chamber works, songs, and much-performed symphonies and orchestral suites. He took over the Frankfurt Conservatory in 1878, hiring the great Clara Schumann to teach piano, but died of a sudden heart attack at age 60. The one genre in which he tried unsuccessfully (at the time) to make his mark was opera: four of his six operas never reached performance during his lifetime.

But nowadays, opera companies, eager to explore works beyond the several dozen most famous ones, have begun to give Raff’s operas a chance, with gratifying results. I reported here on the enchanting first recording of his romantic comedy Benedetto Marcello (based freely on two important composers of the early eighteenth century: Marcello and Johann Adolf Hasse) and his five-act grand opera Samson (composed shortly before Saint-Saëns started composing Samson et Dalila).

Compared to Samson and even Benedetto Marcello, Die Eifersüchtigen (written, like them, to his own libretto, and completed shortly before his premature death), can startle with its bustling, joshing tone. Briefly, there are two noble couples, each of which (as in Benedetto Marcello) clearly has to end up together: Don Giulio (the action takes place in his villa) and Donna Rosa (who are tenor and soprano); and Don Claudio and Giulio’s sister Donna Bianca (high baritone and mezzo-soprano). The matter is complicated by several factors, including Giulio’s shyness and the fact that Claudio’s father, Don Geronimo, prefers that his niece, Donna Rosa, marry Claudio, though she is (as the booklet nicely describes) “an unruly handful.” There are sneaky doings and misunderstandings along the way, engineered by the servants Beppino (baritone) and Ninetta (deep mezzo, at least as cast here), and Claudio gets locked in a cell at one point (by Giulio’s servant Beppino), supposedly for his own protection. But the two noble couples end up aligning themselves correctly, and Ninetta agrees to join the household of Giulio and Rosa, thus enabling her and Beppino to become a third happy couple. (A fuller synopsis is in the booklet, available open-access at www.naxos.com.)

Previous writers have compared Die Eifersüchtigen to Mozart and Rossini, but I also hear other echoes in the work, not surprising for a work written in 1880-81 by someone who had been composing since the early 1840s. For example, the prelude to Act 1 contains a lovely modulation that resembles Dvořák, and the servant Beppino’s first song contains a recurring refrain that parallels musically the number in Carl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischütz in which the wealthy farmer Kilian (early in Act 1) taunts Max. Several arias are relatively simple and strophic, suggesting that the work is partly rooted in the long tradition of Singspiel (including relatively recent instances—some of which would remain in the repertory for nearly a century—by Otto Nicolai and Albert Lortzing). The slow movement of Donna Rosa’s entrance aria is folklike in wording—“Ach mein Sinn, / Sonst so froh, / Ist dahin, / Weiss nicht wo”—which I might approximate in English as “My poor mind, / Once full of cheer, / I cannot find: / Don’t know where.” My longtime musicological colleague and co-author Jürgen Thym has pointed out to me that Raff’s words here are very closely modeled on the purposely “simple” refrain of Gretchen’s Spinning Song from Goethe’s Faust. Indeed, I’d suggest that the style of this short movement is not just folklike-naive but specifically Tyrolean, with gentle yodel-like melodic phrases in the vocal part (though Bianca, as far as we are told, does not come from some Alpine village but, like her brother Giulio, has always lived in Florence!).

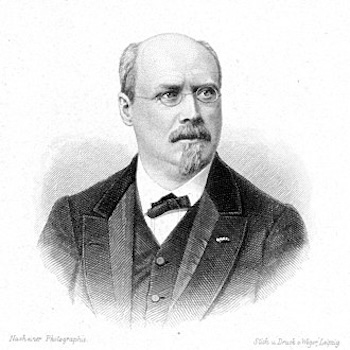

Composer Joachim Raff. Photo: WikiMedia

I was several times reminded of Berlioz, especially in a few passages with scampering, scherzo-like figuration in the orchestra to echo the agitation of the onstage characters. If you know Benvenuto Cellini and Béatrice et Bénédict, you’ll have an idea of what I’m thinking of. Raff surely heard Cellini when it was repeatedly performed (for two seasons) in Weimar, while he was living and working there.

More generally, the frequent recitative-like narrations and dialogues (sung, not spoken) are supported by an extremely colorful and varied musical background that echoes the actions and feelings of the various characters in ways analogous to what Wagner did in his mature operas and also, it should be stressed, what Verdi—in his own way—did in his operas. (Think of the eerie Sparafucile scene toward the end of the first act of Rigoletto.) For example, in Act 3, Raff offers a brief slow melody over a Baroque-style “walking bass” when Beppino, guarding the imprisoned Claudio in Giulio’s palace, notices Claudio’s father Don Geronimo and two other characters coming (end of scene 3). This musical evocation of a solemn procession immediately reminds us of the man’s power and authority. And processions—and Italy itself—are again evoked a minute later (end of scene 4) when Giulio himself shows up, supported by an unmistakable quotation from the second movement (the pilgrims’ march) from Mendelssohn’s Symphony no. 4 (“Italian”).

I found the frequent shifting of musical styles in the work at once engaging and distracting. Perhaps in this respect, too, Raff would have benefited from getting his operas performed and from subjecting them to critical responses, instead of writing for the desk drawer.

Still, this is highly accomplished music. Numerous intriguing passages feature one or two wind instruments throughout, often interweaving with the voice, whether in aria, duet, or larger ensemble or in those many accompanied narrations and dialogues. Though the plot has been dismissed (including by Raff’s main biographer—his daughter) as lightweight and the work as overly long, I found the characters intriguing, and the music held my attention throughout. Besides, like Raff’s Benedetto Marcello—and despite all its musical richness and sometimes elaborate plot—the work is nearly two hours shorter than Wagner’s Die Meistersinger!

The recording is clear and balanced, made (under studio conditions, I believe) in conjunction with the world-premiere performances in Zurich (or the nearby village of Arth—sources disagree). The singers, who seem to be mostly native German-speakers, put the busy text across persuasively. I was glad to hear the dulcet tones of the four lovers and the servant Ninetta and would be delighted to do so in other operas as well. The baritone who plays the servant Beppino digs into his text quite persuasively, though his tone is a bit coarse (as is that of the bass playing Giulio’s father, Geronimo). Finnish conductor Joonas Pitkänen keeps the chamber-sized Orchestra of Europe on its toes. The 36 players carry a wide diversity of names, including some that are clearly Spanish, Czech, and Turkish.

The Orchestra of Europe. Photo: Naxos

The vocal parts seem to have been kept within a natural compass, and there are a few florid moments to show off a soprano’s abilities and suggest her character’s vivacity. I could imagine this opera being performed successfully by student and regional opera companies, perhaps especially if a good singing translation could be made into English. Alas, the libretto in the booklet is German-only. Fortunately, Volker Tosta informs me that a translation will soon be available on his website (www.edno.de).

I suggest that Naxos, in the future, urge opera companies whose recordings they release to offer, in the booklet or online, an English translation of the libretto. And to put the original and the translation in parallel columns, with vertical lines for passages that are sung simultaneously.

That one problem aside, this premiere release, plus the aforementioned ones of Benedetto Marcello and Samson, confirm my sense that Joachim Raff was one of the most accomplished, refined, and, in his own way, inventive composers of the nineteenth century. I urge anybody who loves the music of Mendelssohn, Berlioz, Wagner, Brahms, or (perhaps the closest parallel to Raff) Gounod to give this long-forgotten composer a chance.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music and Senior Editor of the Eastman Studies in Music book series (University of Rochester Press), which has published over 200 titles over the past thirty years. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, and Classical Voice North America (the journal of the Music Critics Association of North America). His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here, lightly revised, by kind permission.

Tagged: "Die Eifersüchtigen", Joachim Raff, Joonas Pitkänen, Naxos