Fuse Movie Review: An Immensely Rewarding Cave of Forgotten Dreams

The beauty and power of Chauvet’s art, at once primal and sophisticated, tempers director Verner Herzog’s passion for Homo Sapiens bashing. We do, after all, belong to the very same species as those cave painters.

Cave of Forgotten Dreams. Directed by Werner Herzog. At various New England cinemas.

By Harvey Blume.

It was with some foreboding that I went to see Verner Herzog’s latest film, Cave of Forgotten Dreams. Would he ruin what was likely to be superb cinematography of this most ancient known example of cave art—circa 32,000 years old, which is to say, nearly twice as old as the storied paintings at Lascaux—by concluding with a soliloquy about what a misbegotten species we have turned out to be? That is how he ended—and in my view, all but spoiled—his Encounters at the End of the World (2007), an otherwise captivating documentary about Antarctica, its fauna, its geology, and its committed coterie of scientists.

Herzog is drawn to adventurers, intellectual cum physical edge players and risk takers. In Aguirre, the Wrath of God (1972), he put himself, his crew, and Klaus Kinski, his star, in danger by climbing mountains, braving rainforests, and doing camerawork on a raft subject to the tides, falls, and eddies of the Amazon River. In La Soufriere (1977), Herzog put himself at risk once more, resolving to document the fate of a peasant who refused to be evacuated from Guadeloupe even though its volcano seemed on the verge of an eruption that, had it occurred, would have buried everyone on the island, not excepting filmmakers. In Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), it is Dracula himself, played by Kinski, who tests existential limits: though the sun is rising, the vamp refuses to cut short his rapturous sampling of Isabelle Adjani’s blood or terminate his romantic discourse with her. (It is tempting to think of Herzog’s long relationship with the volatile Kinski, who died in 1991, as his version of sustained, psychological edge play.)

The title of Herzog’s Antarctica documentary, Encounters at the End of the World, would apply as well to any number of his films and suits his work as a whole. Besides cinematography, the film’s virtue lies in Herzog’s teasing out the eccentric brilliance of the band of scientists fascinated by the frozen continent’s life forms and seas. Then, in an extended voiceover Herzog, in effect, turns his back on these researchers and their efforts, by droning on, above grating music, about how we as a species have long since broken with nature and have only ourselves to blame for doom. Herzog is not interested in raising consciousness about inconvenient truths. He could care less about controlling carbon emissions or greenhouse gases; such details are beneath him. If anything, Herzog is energized by apocalypse, perversely cheered by prospects of Götterdämmerung. He favors that finality.

Cave of Forgotten Dreams is much less bleak. The vision of our species as a scourge is stated, to be sure, but not as obnoxiously. It takes the form of a postscript: not far from the caves of Chauvet, a French nuclear power station makes use of the hot air arising from cooling processes to sustain a massive greenhouse, within which there flourishes a truly bizarre looking cohort or subspecies of albino crocodiles. Though this greenhouse is sealed off and enclosed, Herzog invites viewers to think these mutant creatures may one day work themselves through underground aquifers to streams connected to the caverns of Chauvet, bringing albino croc tidings of collapse, meltdown, and radiation. That said, it remains the case that the beauty and power of Chauvet’s art, at once primal and sophisticated, tempers Herzog’s passion for Homo Sapiens bashing. We do, after all, belong to the very same species as those cave painters.

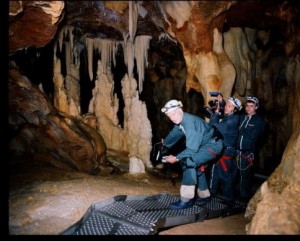

You and I will never set foot in Chauvet. Our very breathing would contaminate it with mold, as has happened at Lascaux, from which visitors are now therefore banned. Herzog was privileged to be granted the access to Chauvet he enjoyed—with a skeleton crew carrying minimal equipment and obeying severe time constraints. We benefit from the results. Along with his Teutonic gloom, Herzog has been driven by fanatic love of imagery. His camera gives a rapturous account of Chauvet—not only the art per se but the way it has merged into the winding walls to the point that art and geology are one.

We don’t know what the meaning of this work was to those who made it. We do know humans never lived in those caverns. Was it a museum for them, a place of worship, a Paleolithic artist’s studio?

The movie floats all sorts of questions it doesn’t make much of an effort to answer. What happened to the cave lions portrayed at Chauvet? Did we send them packing or was it climate change? What happened to the Neanderthals who were still numerous in the vicinity? The film suggests we prevailed against them because of aesthetics: they just didn’t make art. Is any part of this allegation remotely credible?

My main criticism of the movie is that it pays insufficient attention to the formal properties of the art, the ability, by these early painters, to represent perspective and movement. Heated arguments have broken out on this subject. Were the painters visual savants? Did they enjoy psychedelic enhancement?

Herzog might have dwelled on such questions at greater length. But that’s not the kind of movie he likes to make. The one he did make is immensely rewarding.

i wd definitely never buy a used — or new — crocodile from herzog, albino or otherwise. see:

http://www.slate.com/blogs/blogs/browbeat/archive/2011/05/13/fact-checking-herzog-s-ecstatic-truth-are-those-alligators-really-radioactive-mutants.aspx

What did you think about his (in my opinion) preposterous assumption that a nub of incomprehensible rock formation was, in fact, a fertility goddess? And, once having offered that completely confusing commentary, never addressing the fact that there are no other humans in any of the paintings, only hand prints?