Book Review: “The Jazz Omnibus” — The Ultimate Box Set of the Best Jazz Writing from the Last 25 Years

By Allen Michie

Everyone who loves jazz, or makes a living somewhere in its world, owes a debt to many of the hard-working and under-paid writers of the Jazz Journalists Association (JJA).

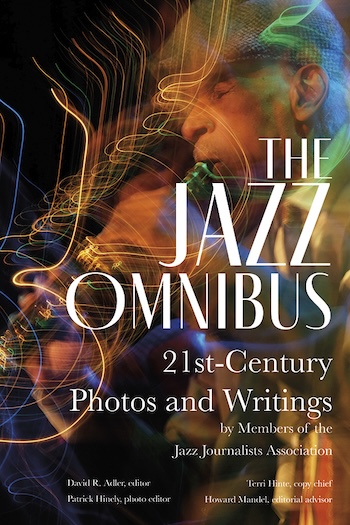

The Jazz Omnibus: 21st-Century Photos and Writings by Members of the Jazz Journalists Association – Edited by David R. Adler and Patrick Hinely. Cymbal Press, 600 pages, $39.95.

“Writing about music is like dancing about architecture,” as someone once said (I’m pulling for Thelonious Monk), and the famous quote does capture something of the futility of inter-species cross breeding in the arts. But isn’t it also true that you’ve cultivated your own taste in music at least partially through the many record reviews, artist profiles, and interviews you have read over the years? That’s certainly an article of faith here at the Arts Fuse.

“Writing about music is like dancing about architecture,” as someone once said (I’m pulling for Thelonious Monk), and the famous quote does capture something of the futility of inter-species cross breeding in the arts. But isn’t it also true that you’ve cultivated your own taste in music at least partially through the many record reviews, artist profiles, and interviews you have read over the years? That’s certainly an article of faith here at the Arts Fuse.

Jazz, already one of the more literate and literary musical genres, is particularly dependent on its great writers. Jazz can be difficult, and it often takes some explaining. Few are going to understand the music of Ornette Coleman, let alone those like Albert Ayler and John Coltrane who followed him, without the help of a gifted and informed writer along the way. On the other end of jazz history, you may not be able to get past the ricky-tick, cornball sound of early Louis Armstrong, King Oliver, and Jelly Roll Morton until a writer like the late Terry Teachout gives you the keys to unlock their genius. The Jazz Omnibus: 21st-Century Photos and Writings by Members of the Jazz Journalists Association contains pieces where the authors admit they didn’t “get it” at first, and they walk you through their process of dawning appreciation: Ted Gioia on Amy Winehouse, Peter Gerler on Charlie Parker.

Also, jazz is just plain fun to read about. It’s full of colorful, opinionated, tragic, hilarious, epic, and eccentric characters. If you’re only listening to the music of people like Charles Mingus, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, Jaco Pastorius, Chet Baker, Charlie Parker, just to mention a handful of the classics — you’re missing half the story, and that means you are not hep to understanding why their music sounds the way it does. On top of that, there are the less famous musicians you’ll read about here, some of them full of wisdom and integrity, such as Portland teacher and trumpeter Thara Memory who one day approached Miles Davis. “I bet you can’t play worth a shit,” Davis said. “Well, no, not compared to you I can’t,” Memory replied, “But I can hold down my own thing and bring some people up with me.”

Everyone who loves jazz, or makes a living somewhere in its world, therefore owes a debt to many of the hard-working and under-paid writers of the Jazz Journalists Association (JJA). According to the short and informative introduction by Howard Mandel, the organization was founded in 1986, and the writers pretty much behaved like the jazz musicians they covered. “Many of us hung out over food, drink and/or smoke to schmooze, gossip and hone one-upmanship, share stories and trade news, play pool, bowl, explore.” The group became officially incorporated in 2004 and started their own publication, Jazz Notes. Today, it hosts star-studded award ceremonies, has conferences, supports educational programs, projects a strong social media presence for news and jazz advocacy, provides equal inclusion for top jazz photographers, and much more. “Jazz, however broadly or narrowly one defines it, is complicated, multidimensional, arguably a universe unto itself,” Mandel writes. “The Jazz Journalists Association exists to substantiate that treating jazz in any and all media as a subject for serious consideration is a respectable, worthy activity.”

With Mandel’s advise, the JJA has assembled The Jazz Omnibus, a powerful anthology of 67 articles (including reviews, features, interviews, liner notes, and historical scholarship) and 23 photos, each by a different member of the JJA. All the writings (but not all the photos) were previously published between 2004 and 2023, and JJA members were asked to submit their own choices from their best work. Entries are sensibly divided into loose thematic sections: Legends, Seekers, Scenes, Sounds, The World, and Remembered. It’s like the ultimate box set of the best jazz writing from the last 25 years.

With apologies to many of the 67 fine authors who will be overlooked in this short review, I’ll point out a few threads I found through the various pieces.

There are the writers who are excellent at knowing how and when to disappear. A few florid pieces try a bit too hard; for example, Greg Burk’s piece on heavy metal and video games strains to fit jazz in there somewhere. (Thank goodness we were spared any of Stanley Crouch’s hyperventilating liner notes to Wynton Marsalis albums.) Mostly, though, great writers cede the spotlight to their eloquent subjects. Michael Jackson’s interview with Keith Jarrett is one of the best things I’ve seen in Downbeat in recent years, not only because of Jackson’s unobtrusive expertise, but for the way he lets Jarrett look to the past to redefine himself in his own words regarding a new phase in his life. There are similarly powerful interviews with Amina Claudine Myers, Marsalis, Sonny Rollins, and Mary Halvorson. Paul de Barros contributes a heartbreaking article that presents the voices of musicians debating coming home to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

A related art in jazz writing is the artist profile. At their best, these pieces maintain a fine balance between background, explanatory prose, quotations from fellow musicians, and personal insights, all the while capturing a sense of their subjects’ personalities and styles. These writers need to be able to see the forest for the trees, but also be able to shimmy up a few of the individual trees along the way. Standouts include Bill Milkowski’s portrait of John Zorn and his work ethic, Nate Chinin’s look at the influence of Sun Ra (Craig Taborn says, “Really there was an eight-year period where he did a species of everything that had been done or was going to happen in a 40-year orb”), Rick Mitchell’s piece on Kendrick Scott’s roots in Sugarland (near Houston), Neil Tesser’s tear-stained remembrance of Von Freeman, Suzanne Lorge’s subtle portrait of Carla Bley, Michael J. West’s balanced assessment of Emily Remler, and Devra Hall Levy’s reminder of Gerald Wiggins’ historical importance.

There are some pieces that dance quite elegantly about architecture, particularly in the concert and record reviews that require capturing compelling sounds in words. At their best, the reviews make you want to put the book down and check out this music right now, as in Andy Senior’s review of a Cécile McLorin Salvant concert (“Salvant expresses more rage with a whisper than a heavy metal band with a stack of cranked-up amplifiers”), or Greg Masters’ liner notes to Miles Davis’ The Cellar Door Sessions 1970 (“This is an entirely new uncategorizable beast — an amalgam of funk, rock and traditional jazz. The music is unlike anything. Comparisons are futile”).

Jazz Omnibus contributor Howard Mandel: “The JJA exists to substantiate that treating jazz in any and all media as a subject for serious consideration is a respectable, worthy activity.”

Given this is a long book filled with mostly short pieces, there’s a temptation to skip around. But I encourage you to read the volume through, or at least don’t neglect articles on the musicians who may be new to you. One example among many is Corey Hall’s feature on Harrison Bankhead, deeply respected by his peers in Chicago. One of the strengths of the book is its comprehensive portrait of the various kinds of lives that thrive in the jazz business. You’ll find several of the strongest articles about unfamiliar musicians in the “World” section, such as Ashley Kahn’s ASCAP award-winning interviews with American musicians living in Europe (“I come from the ‘hood, man, and I’ve really just been figuring out things as I go along, learning from the right places, the wrong places, from mistakes, and trying to become a better person as a man, as a husband and as a father”—Joe Sanders), and Andrew Gilbert’s research on jazz in today’s Israel (the VP at Berklee said, “If I had three days to find ten really hot jazz musicians, I’d go to Tel Aviv before any other place on the planet”). It’s heartening to read the pieces about the optimism and dedication of some of jazz’s great teachers, famous and obscure: Mark Stryker on Barry Harris, John Edward Hasse on David Baker, and Michael Pronko on a high school band director and his students in Kanagawa, Japan.

Then there are the pieces that are just a hoot. “Ornette Throws Great Parties” by Howard Mandel reads like a parody of one of jazz critics’ harmless competitive sports, name-dropping. Nevertheless, you can’t help but marvel at the eclectic who’s-who of jazz that showed up to Coleman’s apartment for a birthday party in 2012 and wish you had been a fly on the wall. One of my favorites is Dorothy Longo’s short remembrance of how Dizzy Gillespie and his band often stayed at her family’s house in Fort Lauderdale, horrifying the white neighbors who would call the police when they saw Black people swimming in the Longo’s pool. Dan Bilawsky’s collection of quotations from musicians commenting on the closure of Bradley’s piano bar is at turns funny, nostalgic, and heartbreaking (“At 4 a.m. you had to stop serving. So at about 20 to 4 one of the bartenders would walk through the room, pick out a half dozen musicians and a few other guys, and tell ‘em to go out back. We’d throw everybody else out, and then for about four hours you’d have guys like Tommy Flanagan, Jimmy Rowles, Red Mitchell, and George Mraz playing for their own enjoyment. It was priceless”).

If I had to scrape around for a few weaknesses, I’d say that the jazz scene here looks a little rosier than it may actually be. There are no bad or mixed record reviews. There isn’t anything about the shift to online streaming services, fake AI music, and digital copyright infringements stealing musicians’ incomes. There’s nothing about Smooth Jazz and those familiar controversies — there was probably space here for something about Kenny G and his milky ilk. I would have also liked to see some writers’ perspectives on the media of jazz writing itself: the state of jazz journalism overseas, the life of the freelance record reviewer and liner-note writer (Scott Yanow has written 992 of them as of Feb. 19), the business of jazz book publishing in and out of academia, the shift to Substack for some prominent writers, the vibrant field of jazz poetry and film, and the humiliating catastrophe editor Gregory Charles Royal brought upon the beloved JazzTimes magazine. On the other hand, I recognize that the editors were limited by the nominations that the contributors themselves sent in, so they were given limited latitude in covering everything important that’s going on out there.

Finally, there’s a banquet at the end — an 11-page selected bibliography from almost all of the authors, and a 39-page index that must have been a beast to put together.

The authors here are the journalistic equivalent to what Sonny Rollins says of his musicians in the very first article: “These people are of a high caliber, and I’m looking forward to hearing some things that I haven’t heard before, and being in the middle of the jazz experience, which is what it’s all about. This is the instant creation. It’s like food to me. This is why jazz is the music of today, tomorrow and forever, because things are happening right then.”

Allen Michie works in higher education administration in Austin, Texas. You can find an archive of his essays and reviews at allenmichie.medium.com.

Tagged: "The Jazz Omnibus: 21st-Century Photos and Writings", Cymbal Press, Howard Mandel, jazz journalism